Imagine inheriting part of the collective trauma of a country — only to find that that very country rejects you, not seeing you as one of their own. This is what happened to David Takashi Favrod. Born to a Japanese mother and a Swiss father in Kobe (Japan), he grew up in Switzerland. With his father frequently traveling for work, he was mostly raised by his mother. “When I was 18,” he writes in the back of Gaijin Omoide Poroporo Hikari (published by Kodoji Press), “I asked for dual nationality at the Japanese embassy, but they refused because it is only given to Japanese women who wish to acquire their husband’s nationality.”

Reading these words brought back memories of how my native country, Germany, had treated the children of so-called guest workers. Even as they grew up as Germans with parents from a different culture and background, up until very recently they were unable to obtain German citizenship. I’m also reminded of the situation of author Miri Yu. Born in Japan to Korean parents, she writes her books in Japanese and has won a number of the country’s most prestigious literature prizes. And yet, she’s a citizen of South Korea. Yu’s incredible Tokyo Ueno Station is available in English translation and you might as well read it. If you want to learn more about Zainichi Koreans in Japan, this article is a good start.

The background of the German and Japanese situations is the countries’ profoundly problematic idea of their own identity as a nation: what does it mean to be German or Japanese? At the macro level, in the middle of the 20th century both countries committed mass atrocities in neighbouring countries because of an imagined superiority. At the micro level, the level an individual such as Yu or Favrod finds her or himself in, the larger tragedy dissolves into a very personal one: who or what am I? Or, in Favrod’s case, why can’t I be Swiss and Japanese? It is from that position that Gaijin Omoide Poroporo Hikari was created.

Of the words in the title, gaijin might be the one that’s most likely to be at least somewhat familiar to a non-Japanese person. It means “foreigner”. Depending on circumstances, you might find that it is used in a pejorative fashion in Japan (which, another parallel, is also true for the German word “Ausländer”). Originally based on a manga, omoide poroporo is the title of an animated drama from 1991 whose English title is Only Yesterday. The Japanese title translates as “memories come tumbling down” or “memories like falling rain” (the latter is given by Favrod in his book). Lastly, hikari is Japanese for “light” (the noun, not the adjective).

“This work represents my compulsion to build and shape my ow memory,” Favrod writes. “To reconstitute some facts I haven’t experienced myself, but which have unconsciously influenced me while growing up.” Since by construction, photographs can only show what is and not what is not, the artist employs a number of tricks to produce some of the images: something might be constructed or staged, something might be created using Photoshop, or something might be presented as something else entirely through the use of text.

In fact, every image in the book comes with a small snippet of text superimposed, making the book serve as a visual index of its maker’s identity. Some of these entries are explained in the back of the book. If you don’t know what “Godzilla” is, the text in the back will provide you with the necessary background to understand its relevance (hint: it’s more than merely a cheesy movie monster). However, I think that some of the texts explain too much: I don’t really need to know all the thoughts behind some of his artistic decisions. But this is a small detail that doesn’t take away from the book’s overall achievement.

Given that the imagery moves in between Switzerland and Japan and between the completely mundane and the vastly tragic, looking through the book transports its author’s struggle with his identity to a viewer who finds her or himself attempting to make sense of it all. The use of archival family photographs provides an essential element: the constructed photographs are well done and often clever (Favrod studied at ECAL), but cleverness is unable to convey emotional drama. That’s where the family snapshots come in, to powerfully deliver that element.

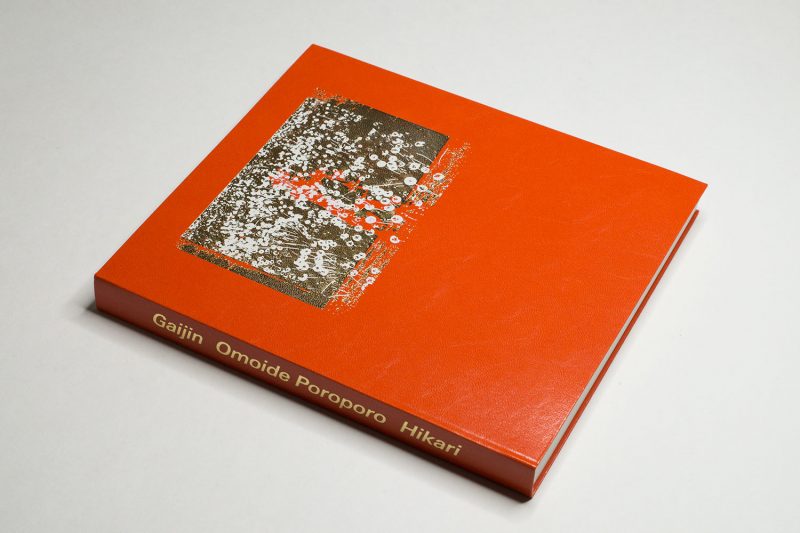

A review of this book would be incomplete without a few words about the object itself. I’ve long maintained that the form of a photobook should reflect the times when it’s published. There really is no reason to produce photobooks today that look as if they had been made in the 1990s. And yet, many publishers do exactly that (no need to name any names, we all know who they are). Gaijin Omoide Poroporo Hikari stands in stark contrast to those books. It’s a book that looks and feels very contemporary with its very smart and elegant design and production choices. Some of them I hadn’t even seen before (for example the title page on the end paper). This makes for a brilliant package that helps elevate the work it showcases.

Very highly recommended.

Gaijin Omoide Poroporo Hikari; photographs and texts by David Favrod; 344 pages; Kodoji Press; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!