“In the autumn of 2021 and summer of 2022,” Keiko Nomura writes, “I had an opportunity to spend a longer while in Poland, in Wrocław. I felt that Wrocław — a city of flowing rivers and lush scenery — resembles Tokyo a bit.” While I wouldn’t want to claim that photographers are superior beings in any way (sorry!), for sure most of them possess a heightened sense for the flow of time as manifested through the change of light. In addition, they know about the quality of the light in any given moment, whether it’s warm or cold — and what implications this might carry in their pictures.

If you approach the world in this way, superficial similarities and differences between two locations that seemingly are as different as Tokyo and Wrocław will fall away. Even the differences between the lives of their denizens fall to the wayside. In their place arrives an understanding of their shared being human. (I’m avoiding the word “humanity” because it doesn’t quite get at what I’m after, in part because the word can be too easily tied to the wrong concepts.) Of course, that understanding is the photographer’s first and foremost, even as it can — and in all likelihood will — be shared with their audience.

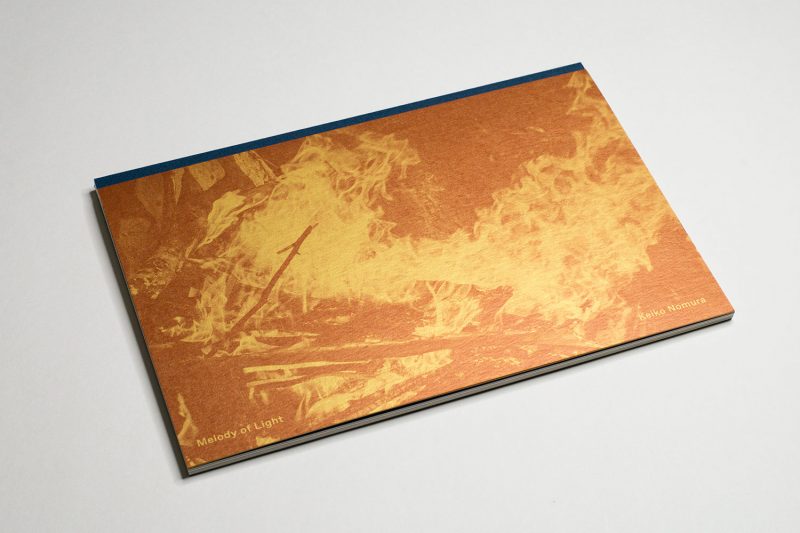

All of the above sounds pretty abstract. It’s easier to see it (or rather feel it) when encountering a photographer’s work. In this particular case, I’m speaking of Melody of Light, the book from which I quoted Nomura’s words (the book is also available from the photographer herself, but you might need to be able to read Japanese to order it).

It’s the kind of book where the more words you try to attach to it to describe what it conveys, the farther away from it you get. For example, the publisher writes that in the book, “Keiko Nomura explores such topics as transience, nature, body, soul travel and the water cycle”. That’s kind of true, yet also incredibly useless, isn’t it? (I don’t mean to give them a hard time.) Ultimately, you’d want to write “Just buy the book and look at it yourself”. But obviously that’s not an option for either a publisher or a reviewer. Oh well.

I’m not going to get any further into trying to describe the work beyond what I outlined above. Like all good photobooks, Melody of Light evokes a very particular atmosphere, which in this case is light and full or promise, even if it is being hinted at that most of the promises will remain unfulfilled. “Just as our life,” Nomura writes (albeit speaking about light), “with the accompanying imminent death, which will be swept away by unstoppable time.”

This is only a grim sentiment if you are too attached to any given moment or, as is probably more like the case, to life itself. But there will always be another morning with as much promise as today’s. It’s up to you to grab the moment and make the most of it — like a good photographer will be cognizant of the right moment at the right time to make her picture.

I currently am unable to shake a sentiment, namely that too many photographers shy away from taking photographs of people. Photographing any topic or idea of course can be done well without showing someone’s face. But more often than not, as a viewer, I am increasingly finding myself wanting to encounter faces in photography (I should probably make it clear that by this I don’t necessarily mean more faces of rugged, underprivileged men somewhere out West — I have seen enough of those, thank you very much).

The reality is, though, that it’s very difficult to come close to any emotional core without the direct presence of a human being. In Nomura’s work, more often than not the faces sit on top of nude bodies. At least that’s the work I am familiar with; looking at what was available during my trips to Japan I ended up buying a copy of her earlier book Soul Blue. There are quite a few nudes (and some clothed portraits) in Melody of Light as well.

To begin with, a female photographer from Japan taking nude photographs of (mostly) Western subjects has me interested on an intellectual level, because it inverts the common model of a male photographer — Japanese or otherwise — taking pictures of Japanese subjects (often young women). Beyond that, though, I am intrigued by the nudes in the book because most of them feel so tender. I would hate to use the word “innocence” in this context. Even as that idea for sure exists, in light of how people have written about nudes, there are too many icky associations lurking nearby.

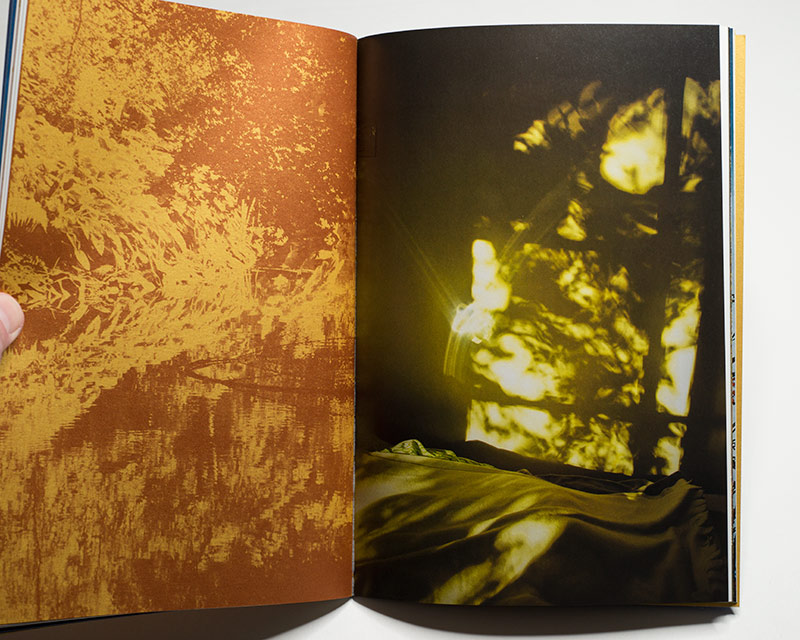

Melody of Light collects these nudes and an assortment of other photographs of cityscapes and nature to immerse its viewers in the beauty of the moment. There are three photographs of shopping areas in both cities that I could have done without (they’re weak pictures), but this fact doesn’t take away from the beauty of the book.

With design by Joanna Jopkiewicz and a few charming and engaging production choices (I like the metallic-paper pages and the way photographs are printed on them), it’s a book that embraces many of the devices that contemporary photobook making has at its disposal. It’s a well considered production that isn’t trying to feel overly precious. I really appreciate this aspect of the book, given that off late, I have become less and less interested in oversized hefty art books.

Melody of Light; photographs and text by Keiko Nomura; 76 pages; BWA Wrocław Galleries of Contemporary Art; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!