When I first looked at Max Zerrahn‘s Snake Legs, I immediately remembered being in Japan with a camera and trying to make a picture. Unless you’re a street photographer or tourist (in which case you’re mostly replicating what other people have photographed before you), Japan doesn’t lend itself easily to photographs if you’re not very familiar with the country. Its surface is either hyperpolished or too quaint.

I suppose I need to qualify the above by stating that obviously, it always depends on what you’re looking for. As someone who has lived in a foreign country for two decades now, I know that it takes a long time before one is able to see in ways that aren’t a foreigner’s any longer.

Outside of the world of the news, I don’t think there necessarily is a reason why an outside or an insider should or should not take certain pictures — as long as they’re both aware of their own shortcomings and as long as they challenge themselves (meaning: as long as they also make themselves aware of the history of their medium), they ought to be able to produce something interesting.

But it’s difficult to make interesting pictures in Japan as a visitor. During my first trip, I gave up all ideas of making something original and shamelessly focused on all those things that were just too obvious to ignore. This included the sheer number of cones (traffic and otherwise — there must be one or more for every Japanese person), the rotating platforms used in garages, covered cars, and a few more things. This ended up being a better exercise than anticipated, and I really got those items out of my system. The second time I went, I barely noticed them any longer.

I see these photographic difficulties weave through Zerrahn’s book. I don’t mean this as a criticism in any way. I have a book of photographs that Nobuyoshi Araki took in New York, and if it weren’t for the presence of the occasional sleazy nude (I suppose he just couldn’t help himself) I doubt anyone would be able to tell who the photographer is.

Actually, I do think that Snake Legs is a lot better than the Araki book, because a lot of the very obvious stuff is not included — or almost not included. There is one photograph of what might be that enormous Shibuya Crossing but it’s small in the book and in black and white. For the most part Zerrahn stayed away from the expected and went out looking for something else.

In the world of Japanese photography, which has been centered on the book, the idea of the single photograph has historically been very different. While Western ideas have obviously made it into the country, the insistence on each and every photograph being a remarkable masterpiece is a lot less important than the whole, the book, communicating something (this obviously doesn’t mean that Japanese haven’t made remarkable masterpiece photographs).

In contrast, our Western ideas seem centered on the individual photograph that ought to be as brilliant as possible. You then build up a “project” in such a way that it’s a coherent “best of” of your good pictures that also happens to communicate something larger. I don’t necessarily find fault with that, because it’s a good method (so it’s great for teaching). But it’s important to realize that it’s only one of the possible methods: there are others.

To begin with, one might wonder why individual pictures have to live in projects after all? Aren’t projects mostly marketing or teaching tools? Why does every picture have to live in a project, and why is a picture only allowed to exist in one project? You’ll notice that there are artists who will deviate from this simple model. But for the most part, the model holds a stranglehold over the world of art photography.

And then there is the fact that the accumulation of photographs that aren’t masterpieces could still result in a truly amazing book. The most well-known example might be Kikuji Kawada’s Chizu (The Map). The book is completely mind blowing in a way that the vast majority of its constituent photographs are not.

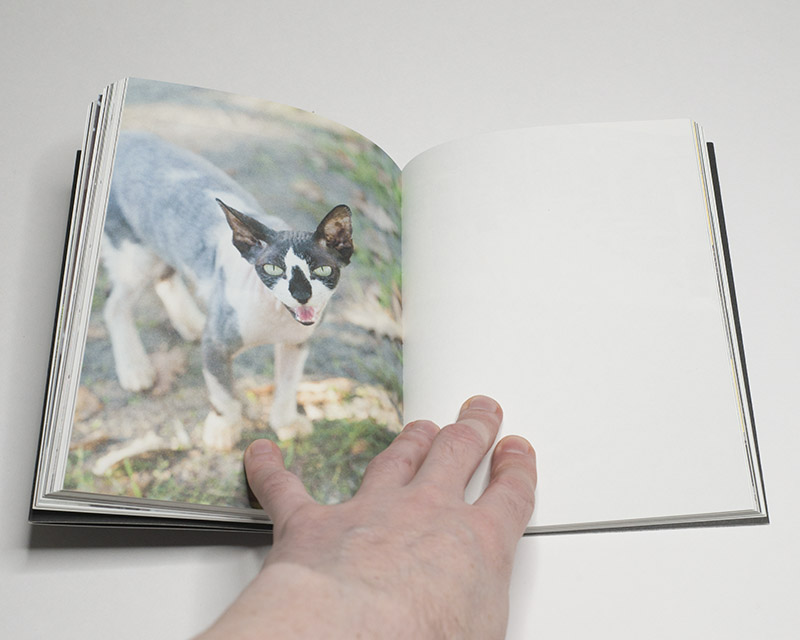

Having now said all of that, I do think that Snake Legs falls into the category of books where the accumulation of a number of photographs produces something a lot larger than its parts. There are pictures in the book that I quite like (obviously, my favourite photographs shows a cat). But the enjoyment of the book comes from going through the book and having its individual photographs slowly add up to more and more.

I suspect that this makes the book a bit of a hard sell: I could imagine picking up the book at some book fair, only to miss what it has to offer by going through it too quickly. Say whatever you want about book fairs or even the internet, but there are a lot of things that just cannot be communicated in brief intervals of time.

The book is also relatively diminutive: at 5.5×7.5″ (14x19cm) it’s at the small end of small books in my library. But this serves as another much needed reminder that more often than not, photobooks are simply too overblown. I get it, you’re working on your photobook, maybe even your first photobook, and you want to make a splash (full disclosure: I’m working on my first photobook right now).

But bigger isn’t always better, and at least in principle looking at a book is an intimate affair: it’s you and the book. Snake Legs feels right in that sense as well. I could imagine taking it on a trip, to look at it while traveling (most of the photobooks I own I can’t bring because they’re too large, too heavy, and/or too precious). And a trip might be the perfect occasion to look at the book — when you’re away from home and find yourself in a location you’re not familiar with.

In light of the above, I’m not going to apply my photobook-rating system here. I like the system for what it allows me to do, but I’ve also come to appreciate the fact that some books just fall outside of its domain.

Snake Legs; photographs by Max Zerrahn; 144 pages; White Belt Publishing; 2019

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.