The most recent prominent German court case dealing with large-scale domestic terrorism spanned four years. Unlike the cases from the 1970s and 80s, this one did not focus on a left-wing terror organization. This time, the defendant was the sole survivor of a group that had called themselves National Socialist Underground (NSU), responsible for a string of 10 murders. The case was remarkable for a variety of reasons, one of the most important ones being that for the longest time, authorities hadn’t been concerned with terrorism at all. Of the ten victims, only one had been not of originally Turkish or Greek origin. In all the other cases, authorities had suspected all kinds of reasons for the murders, many of them connected to their own blatantly racist biases.

In an article in the weekly Die Zeit, journalist Özlem Topçu noted that the long duration of the case notwithstanding, it had been worth it. There had been clear evidence how the trio had had deep ties to Germany’s far-right underground and was thus no conveniently isolated group. Topçu wrote: “And other ugly things have been brought to light: the failure and falsehoods of some intelligence services and investigating authorities. Their partly questionable working methods and their attitude towards the victims.” (my translation)

This is tough stuff, especially in light of a far-right party now sitting in the national parliament, the Bundestag, or with the head of one of the federal intelligence services being removed from his post after he questioned the obvious existence of far-right violence in an East German city. Said far-right party calls itself Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), and German history aptly demonstrates what such an alternative path might lead to.

So there is obvious concern about the open emergence of far-right voices in Germany. But as the NSU case demonstrated, that concern does not appear to be quite as widely shared to the right of the country’s political center or by some of the people in charge of upholding the constitutional rights of all its citizens — and not just the ones the AfD considers as the real Germans.

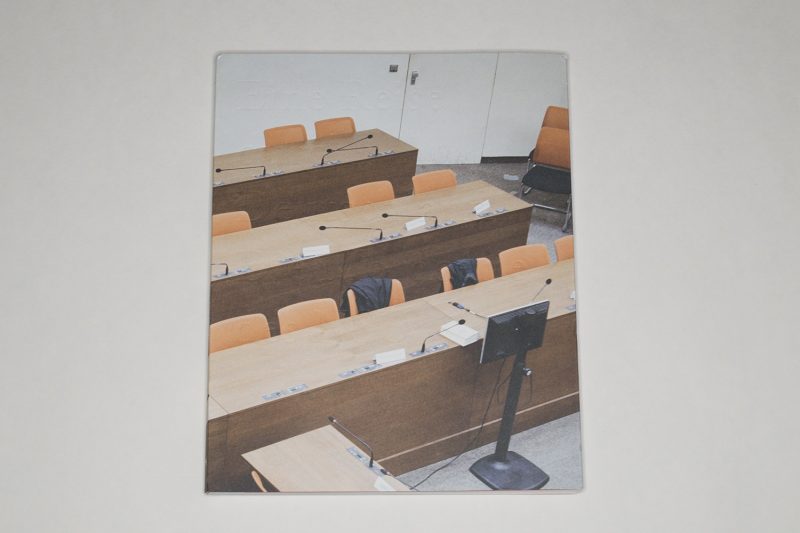

How can you tell such a story with pictures? Well, you can’t, or rather you can’t tell the story with pictures alone. When you open Paula Markert‘s A Journey through Germany. The NSU Serial Murders, the first thing you’ll see are the names of the ten victims, the dates of their murders given under their names. If you’re curious whether there is something contained in the folded cover (the book uses what is commonly referred to as Swiss binding), there is a dedication against a blood-red background: “In remembrance of the victims of the so-called National Socialist Underground (NSU).” (the book is fully bilingual German/English — here, I’m only quoting the English text) And then you might notice that the cover contains more than merely an image of what looks like a German court room: the book’s title is embossed.

I find the use of these devices not only effective but also entirely appropriate. In fact, not even just appropriate but also morally necessary — especially in light of the suffering of the families of the nine victims with migrant backgrounds. After all, this is as much their story as their adopted home country’s. To insist on a separation between the two would only serve to create that gap that serves as the foundation of the racist völkisch thinking of the AfD and other far-right organizations.

So how is the story being told? It’s a combination of photographs that work along the lines of Joel Sternfeld’s On This Site plus portraits plus added text. Unlike in Sternfeld’s case, the captions for the photographs are listed in the back of the book and not right next to the pictures. In addition, there is a variety of texts interspersed with the photographs throughout the book, including extracts from legal texts, court protocols, newspaper reports etc. The separation of the captions from the photographs allows for a space to open up, where the sheer malleability of photography helps tell part of the story.

After all, for many years, the NSU was going about their killing spree without the dots being connected. A photograph of a piece of forest might show the location where a victim was found, but as a viewer you only know that if you’re being told; and even after you know, nothing in the pictures indicates that what you’re looking at is in fact what you’re looking at. This is, in other words, where photographs separate from the world they’re taken in and become something else entirely.

The viewer will thus become broadly acquainted with the story through the Foreword in the book. But the lack of the kind of information later provided in the captions adds an additional charge to the photographs: you know that each picture must mean something in the overall story, you just don’t quite know (yet) what. It’s an effective way of storytelling that makes part of the book positively uncanny. It also produces an emotional charge that involves the viewer in a story that in all likelihood they might not have any direct relationship with.

The book thus is a form of documentary that refuses to be too documentary, that, in other words, is happy with uncertainty seeping in, with viewers being able to feel something that cannot be expressed in words or pictures.

Recommended.

A Journey through Germany. The NSU Serial Murders; photographs by Paula Markert; text fragments from various sources; 112 pages; Hartmann Books; 2019

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 4.5, Edit 3.0, Production 3.0 – Overall 3.6

Ratings explained here.