We largely comprehend this world through pictures, whether we’re taking selfies or photographing a very distant celestial body with a satellite that’s rushing past it with a speed of 16.26 km/s (10.10 mi/s). Every photograph is an attempt to make sense of the world, even if only a few are acknowledged as that — those that we all could easily agree as being documents more than anything.

Regardless of whether a photograph is viewed as a document or not, in all likelihood it is the result of some form of extrapolation, of some form or processing. Astronomical images are heavily processed, with the colours seen in them being often added artificially (based on clearly defined astronomical conventions).

A smartphone operates in similar ways. “By default,” Apple notes, “iOS and a device’s image signal processor perform a number of operations on the data from a camera’s image sensor to create a displayable image. These manipulations include dead pixel interpolation, demosaicing, white balance, noise reduction, tone compensation, and sharpening.”

None, of this, I would argue, matters much — after all, our own brains themselves are known to very selectively stitch together what we perceive as reality (please note that with this statement I’m referring to neurological processes and not to what is currently at display on the far-right side of the political spectrum all over the world).

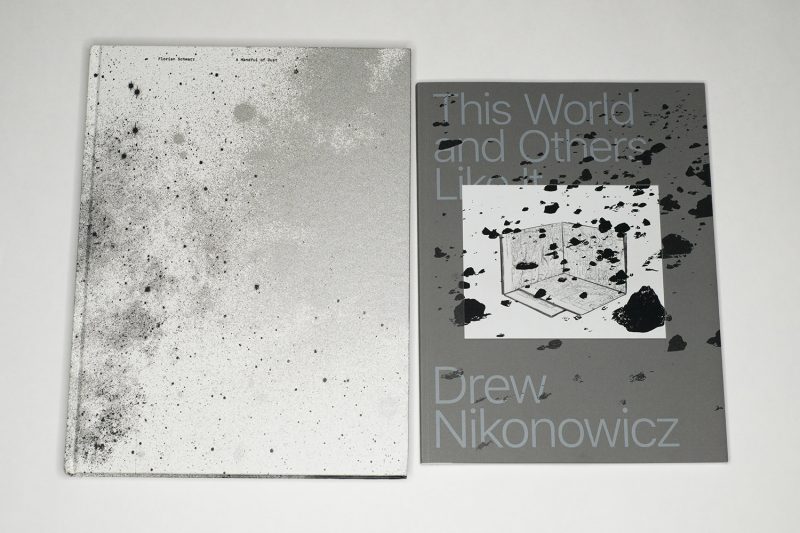

But there is much to be gained from attempting to understand how the process of discerning facts or meanings from pictures — an act of interpretation — plays out. Two recent books use this idea as jump-off points, Drew Nikonowicz‘s This World and Others Like It and Florian Schwarz‘s A Handful of Dust (please note that the latter is not to be confused with David Campany’s book of the same title).

As a brief aside, the books share the same designer, Hans Gremmen (who co-published This World and Others Like It), a fact I only realized after I had decided to review them together.

This being the internet, I should make it clear that these two books are not the same. As I noted, their jump-off point is the same, but they look into the topic using different angles. This World and Others Like It, the more cerebral one, mostly concerns itself with the construction of images and their subsequent inevitable artifice. In contrast, A Handful of Dust plays it more straight, largely ignoring the process of making images and instead tying them to their makers — or consumers — themselves: humans.

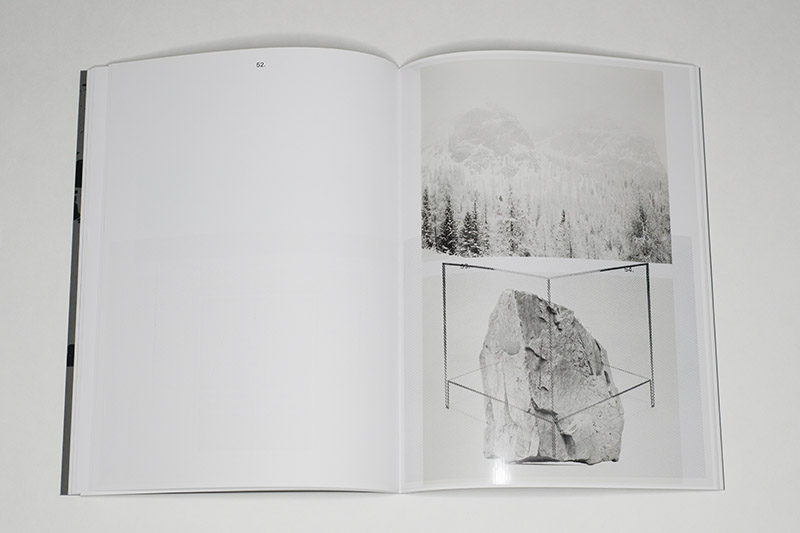

This World and Others Like It starts off with a list of coordinates in time and space — these are, the viewer can infer, the data of the images. But wait, picture 2 is one of the famous 1969 photographs of a man on the moon — how could this have a date of 2014 and a location so close to many other pictures? Well, it’s an image of an image, presumably produced in the artist’s studio: Google Earth shows me the Fine Arts Building of the University of Missouri. And it continues in this vein, with images of images or images made to look like other images or images made to look like they tell you about the process etc. Like I noted above, images are constructs, and the book focuses on that very point.

The work stays right there, at the level of the image — the various degrees of artifice involved in its making and the way we viewers read or interpret it. This is good. The book includes a couple of plastic sheets onto which patterns are printed, further confusing the viewer and adding another tactile element. This is good, too. It is my background — I have a Ph.D. in physics and spent years working in astronomy — that probably has me wanting a bit more, though. I know images are constructed so what else is there?

Over the years, I’ve had the same reaction to what one could call metaphotography. I remember Thomas Ruff once told me something about how astronomers process their images (50% of which was actually factually wrong — I didn’t have the heart to tell him), and I realized that what was completely trivial and obvious to me clearly must be truly fascinating for non-astronomers. My background probably also easily explains why I just can’t get too worked up over image manipulation or construction.

So This World and Others Like It is the kind of book that I’d look at during the day, sitting in my office. It’s very well done. It perfectly caters to my intellect, and I can enjoy it while my reptilian brain is cooking up something else entirely for a later moment.

There is some overlap between the two books in what they show — images that look like other images, but all in all despite an abundance of scientific (mostly astronomical) imagery, the main element in A Handful of Dust that disrupts the cerebral game are the many (straight) photographs of people, many of whom at first do not appear to have any obvious connection to the rest of the book. Who are these people? Why are they there? I found myself intensely drawn to them because through this disruption, the artist gets at the larger topic at hand, namely the quest for knowledge, the quest to make sense of it all.

Looking at A Handful of Dust I found myself skipping most of the astronomical content (from the above it might be obvious why). For example, the pictures of the labs with the various contraptions — that’s what I’d see in one of my university jobs if I left my office and walked straight ahead into the lab across the hallway. I found all the other pictures interesting and intriguing, and the design and production of the book truly work together to enhance what is on view. Maybe it’s the book’s size and design that makes this one a lot more immersive than the other one. It speaks to the sheer brilliance of the designer, Hans Gremmen, to have found the perfect solution for these two books.

So if This World and Others Like It is a book for day-time hours, I’d rather look at A Handful of Dust at other times, when my intellect possibly is a bit exhausted, and when I can soak up some of its feelings. (Writing these sentences down made me realize that I have in fact been looking at these books in exactly this fashion.)

It is as if each book existed to remind the viewer of the missing parts that are contained in the other. And when I say “missing” I don’t want to imply a value judgment. Inevitably, as one focuses on one’s work, the process is one of exclusion, of casting aside elements that have no place, that are unnecessary or unneeded. Nikonowicz’s cerebral and at times cold study of images has no place for a more human component, for photographs of people that are maybe only remotely connected to what’s in the pictures. In contrast, Schwarz never approaches his topic too closely, instead weaving in and out while bringing together what at first sight appear to be unconnected elements.

What do we know? What can we know? I suspect we will always use images to try to find out. In their different ways, these two books bring the viewer closer to understanding the role of images in our lives — and their limitations.

A Handful of Dust; images by Florian Schwarz; texts by Boris von Brauchitsch, Martin Dominik, Arnold Stadler; 232 pages; Kerber; 2019

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.1

This World and Others Like It; images by Drew Nikonowicz; text by Paula Kupfer; 102 pages; Yoffy Press/FW:Books; 2019

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.1

Ratings explained here.