When I grew up, West Germany’s foundational myth was still in place. It roughly went as follows: there had been terrible crimes committed before and during World War 2 by the Nazis. The responsible party for these crimes had been the SS. Nazi Germany’s army, the Wehrmacht, however, had fought honourably, and it had not had a part in any of these crimes. What is more, ordinary Germans simply had not known of the crimes committed in their names.

Even at the time, it was very obvious that this myth could not have been remotely representative of the actual situation in Nazi Germany. There simply was no way that the SS could somehow kill millions of Jewish people in areas occupied by the Wehrmacht, which not only had no part in this but also had no clue. What is more, pretty much every family had a member in the armed forces, and there’s no way families didn’t hear from their brothers, fathers, or son what they had witnessed.

Starting around the time I was a teenager, the foundational myth was firmly shattered by historians who proved that the Wehrmacht itself had not only supported the SS’s murderous quest, it had also actively participated in them, and a large number of Germans had known very well what was happening in concentration and extermination camps.

I see West Germany’s quest to believe in the presumably honourable Wehrmacht reflected in the defense of the many Confederate monuments in the American South. At the occasion of the so-called Wehrmachtsausstellung, a touring exhibition that presented documents and shocking photographs of Wehrmacht atrocities, there were demonstrations by conservatives and neo-Nazis against what they saw a besmirching of an honourable institution.

What’s crazy to me, though, is to see that as far as I can tell there aren’t any secrets any longer about what the Confederacy fought for (slavery). It’s all out in the open. But somehow, tearing down the statues, we are told not just by neo-Nazis but also by what accounts for respectable conservative voices (at least in the US), amounts to an assault on the South’s heritage and an attempt to somehow erase history (the latter bit isn’t clear to me, but I’ll be honest and say that I don’t feel the need to engage with bad-faith arguments). And one of the craziest bits is how many of these monuments exist. It’s not just one here or there.

Part of the reason why this is all so frustrating to observe is because the idea of American exceptionalism is so firmly entrenched in the country, all across its political spectrum. As a consequence, Americans can’t imagine that other people have already dealt with some of the issues they’re facing; and in any case, (for some completely irrational reason) it’s America that ought to be guiding the world — and not the other way around.

This is not to say that Germany has successfully dealt with all of its past — quite on the contrary. Germany’s colonial genocide in Africa has so far been almost completely ignored. Still, if Germany can learn from the US, why could this not happen the other way around? Here’s an interesting interview with Susan Neiman by Isaac Chotiner that deals with exactly how German history might help the US deal with its own racist past.

But the US’ refusal and/or inability to look beyond its own borders is mirrored in a lot of other countries (no exceptionalism there, either). For example, countries such as Britain or Belgium are each attempting to deal with their own racist monuments.

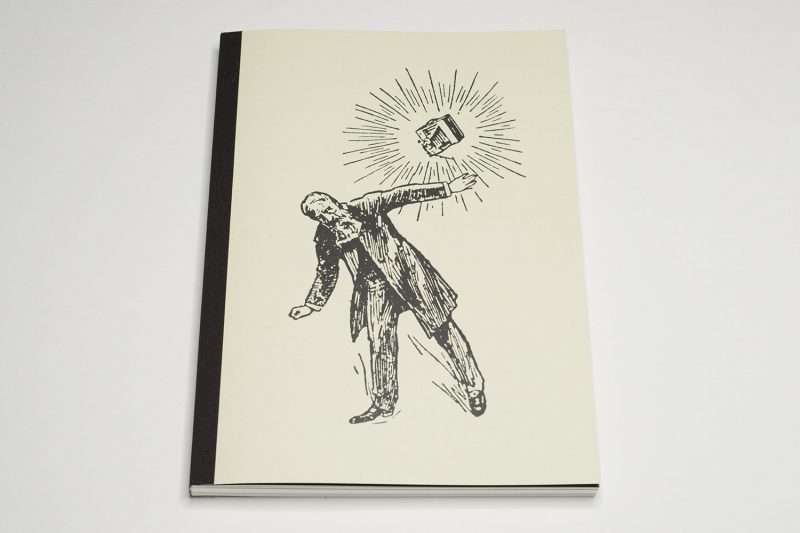

A new and fortuitously timely book by Oliver Leu entitled Leopold’s Legacy shines a light on Belgium’s on-going attempts to deal with its colonial past, in particular the Democratic Republic of Congo, short Congo (but not “the Congo” because the use of the article is part of the colonial past — compare this with Ukraine also not being referred to as “the Ukraine” any longer).

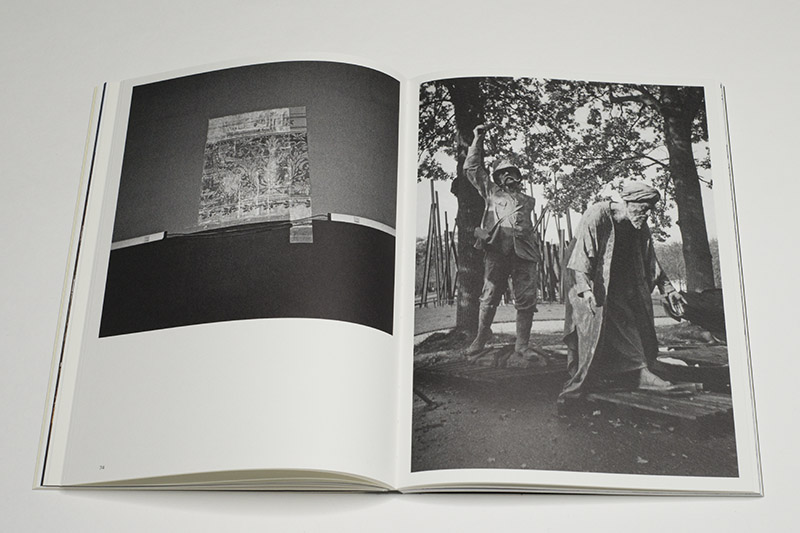

The book assembles a variety of visual materials in a number of sections that each focus on one aspect of visualizations of Congo and/or its still existing representation in Belgium. There are Google Street View scenes of streets named after colonial-era figures, reproductions of vintage postcards that showcase colonial achievements, photographs of the the Belgian equivalent of Confederate monuments, and more.

Crucially, the book contains a number of in-depth essays that each dive into aspects of what is on view, large parts of which I hadn’t heard of before. For example, in the introductory historical essay, Matthew G. Stanard, professor of history at Berry College in Georgia (US), writes about Leopold II: “If at the time of his death in 1909 he was infamous abroad and little loved at home, by the 1950s, Belgians hailed him as a prescient colonial genius who had acquired a massive, resource-rich African territory for his home country. […] While only one monument was erected in the king’s honor before 1908 […], more than a dozen were unveiled in the decades following his death” (p. 18). Compare this with Confederate statues having been erected decades after the Civil War.

Discussing Belgium’s engagement with its past, in particular the many atrocities in what was called the Congo Free State, Bambi Ceuppens, senior researcher/curator at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Brussels, notes that “Belgian memories of such episodes have long been dominated by narrow, simplified, mythologised forms of cloistered memory” (p. 87). Again, one can’t help but think of how the Confederacy has become what many people in Southern states think of as their “heritage”.

In both cases, as time has past and actual witnesses have died, there has been “a shift from communicative to cultural memory — that is, from the interchange of direct (biographical) memory of the recent past between contemporaries, to recalled history” (Ceuppens, p. 89). How and why this has proven to be complex, Ceuppens explains in her essay.

The essay contains a very important discussion of possibly the worst colonial photographs, which have not been reproduced in the book, photographs of severed hands by British missionary Alice Seeley Harris. These photographs are problematic for a large variety of reasons as Ceuppens makes very clear.

I see a partial equivalent in the statue of Abraham Lincoln and an (anonymous) freed slave that the city of Boston just decided to remove: there clearly is a colonial mindset present in the very depiction. In the case of the Lincoln statue, the emancipated man is on his knees in front of the white man. “What I want to see before I die”, wrote Frederick Douglass about a copy of the statue in Washington, DC, “is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”

As Ceuppens points out, such imagery is designed to make its target audience (white Europeans) feel bad instead of inviting them to try to understand and share the pain of those at the receiving end of violence: “By contrast, artworks, diaries, drawings, mundane objects and photographs that speak about the everyday life of victims […] have the power to remind us of our common humanity.” (p. 93)

History is a complex entity, and it is constant need of being amended or re-written. There is no such thing as fixed history. In my own life time, I have witnessed and experienced very drastic changes, speaking just about the country I was born in.

However much those who defend racist Confederate monuments protest (this group sadly includes the present president of the United States and vast parts of his party), these monuments will have to come down. It’s just a question of time. Their presence is indefensible, and the defenses mounted often are little more than dog-whistle expressions of naked racism.

Of course, there is the argument that taking down a statue amounts to an erasing of history. If there were even a kernel of truth to the argument, Germans wouldn’t know about Nazi Germany: there are no monuments depicting Nazi leaders or Nazi generals. It really is only an argument made in bad faith.

Maybe seeing an outside view — the view of Belgium and its colonial past — will help some Americans to come to a better understanding of their own country, to realize that the presence of Confederate monuments and the idea that Black Lives Matter are mutually exclusive. The monuments are an implicit denial of the latter, and for that reason, they will have to come down: the sooner, the better.

Leopold’s Legacy; images by Oliver Leu; texts by Oliver Leu, Bambi Ceuppens, Matthew G. Stanard; 152 pages; The Eriskay Connection; 2020

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.