If analogue photography has developed much of its allure from taking pictures of grimy surfaces, digital photography excels with glossy ones, especially if there is a lot of light around. I wouldn’t want to attribute any deeper meaning to that (at least for now). Over the course of the past two decades, our seeing of the world has been increasingly shaped by how digital cameras describe the world. This development has gone so far that parts of our world are now being created in such a way that they look good in digital pictures.

While in general I am not too interested in photography that seems too camera-technology specific (regardless of whether it’s analog or digital), I do get the occasional kick out of something that is really well done, something that pushes a particular technology to great effect. For me, there is a degree of guilty pleasure in this: I might have spent too much time looking at and attempting to critically write about photography to be able to just enjoy something — unless, and this is rare, the work in question is so strong that it manages by short circuit my critical abilities (this is an exceedingly rare event, given photoland’s sea of visual and conceptual sameness).

The only problem with digital photography pushing shiny surfaces and modern light is that in principle, it’s the same message that also underpins neoliberal capitalism. Your neoliberal realism is often right there, and whatever critical idea a photographer might have had in mind is being undercut by the sheer visual appeal of what often is pretty noxious.

This might be the main difference between capitalism roughly 100 years ago and now: where in the past, getting access to factories was difficult because of the resulting visuals, now, modern factories are almost always open. Neoliberal capitalists are only too eager to have consumers (or images and products) ooh and aah over how shiny robots and human beings arranged around them to present environments that look as if they were taken from some science-fiction movie.

If you think about it, this is a nifty move: we are so conditioned from popular entertainment to view certain things as fiction (or “science fiction”) that by performing that mental association, we don’t realize to what extent we are in deep, deep trouble already. The disaster has arrived, but it’s looking pretty great in pictures.

As Bertolt Brecht already noted, both one hundred years ago and now photographs won’t get at the underlying ideologies and mechanisms of exploitation. But today, workers don’t look exploited any longer — even if they are as abused as their colleagues a century ago.

If you’re a photographer, how do you avoid this problem? I have no idea. What seems clear is that individual photographs will not be able to do the job (see Andreas Gursky or, to pick another example, Edward Burtynsky’s photographs from inside factories in China). It might only be the combination of such imagery in the form of a photobook that offers a chance to create a fissure in the facade (obviously, I’m not talking about a catalogue or monograph of individual photographs here).

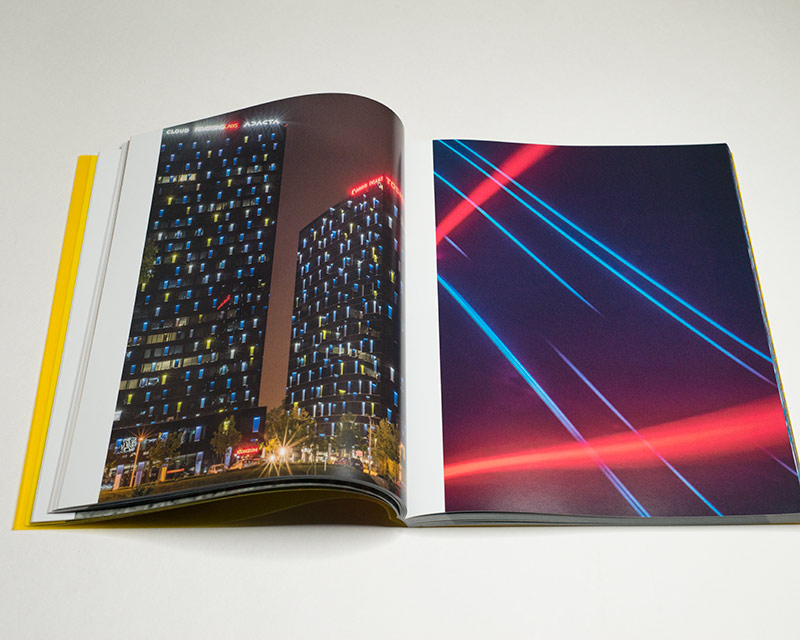

Cristiano Volk‘s Laissez-Faire showcases contemporay life under neoliberal capitalism in all its shiny glory where tackiness always is but a step away (if even that). “[I]t’s all about the meat baby”, a neon sign advertises in one picture (one shudders to imagine what might be on sale), while in another the names of corporate brands (Canon, Toshiba, …) tower high over municipal high rises. It’s not clear what exactly the buildings are — office or apartment towers? But it doesn’t really matter. Either way, the life experience they offer is shallow (again: if even that).

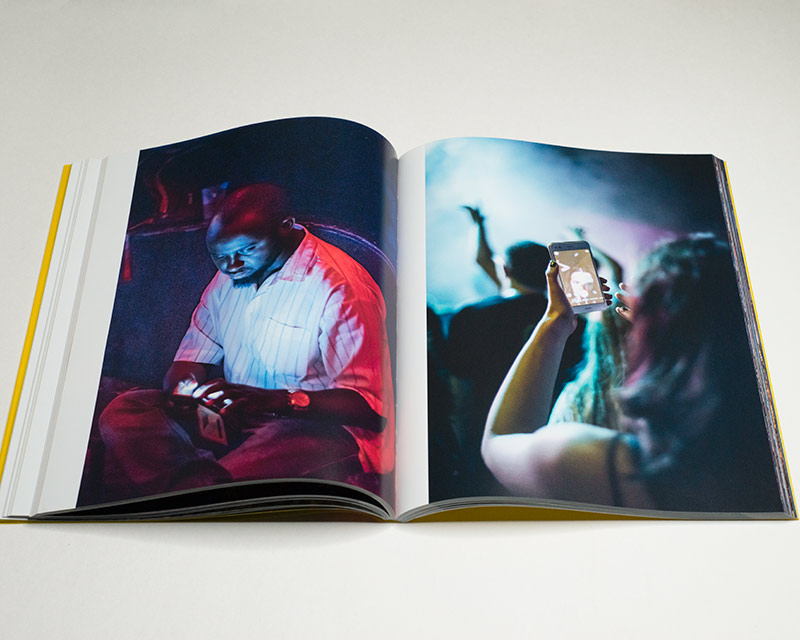

And so it goes on and on, with colourful lights being captured the way we are used to now, where everything not only is made to look good in a picture but also can be easily captured in one (given how well modern camera sensors and associated algorithms are able to work with what previously was low light). Perhaps not surprisingly, everybody is having the good time on offer, and everybody looks great (even sea life in some aquarium).

Leisure time and work life seamlessly transition into one another in the book. This makes sense, given that neoliberal jobs require being present 24/7. When we’re on our gadgets, we work for free for the makers of the various social-media and messaging apps that promise to connect us to the world.

I don’t know whether Laissez-Faire offers me anything that I don’t know already. But if photography wants to create that fissure that I spoke of before it maybe might result less from some Brechtian Verfremdung and more from relentless exposure. Maybe at some stage, we will realize how we have created an environment for ourselves that is only serving a small number of billionaires.

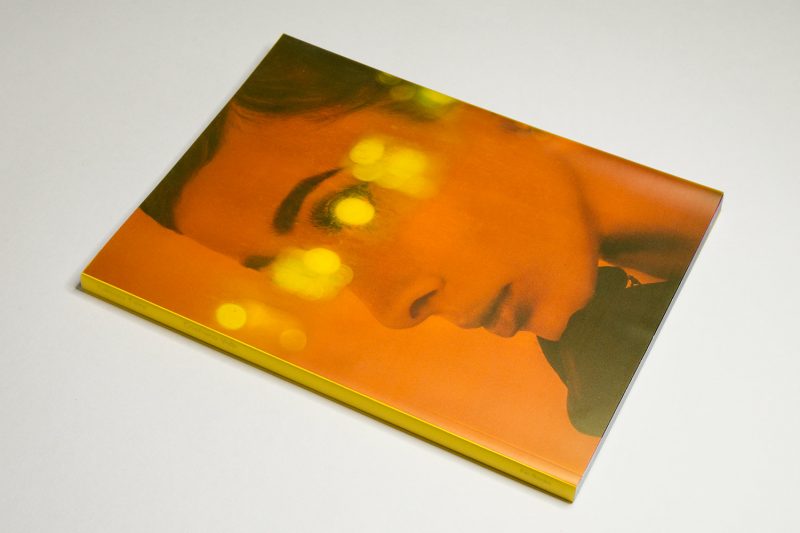

For sure, the book comes appropriately packaged. There is a bright yellow plastic dust jacket around the softcover, which inevitably has the book stick to my hands in ways that I want to wash off (it’s not helping that while I’m writing this, it’s 33 degrees outside, a new record in late May as the news told me). But what I really want to wash off, of course, is not so much the book but rather the way it makes me feel.

I hear neoliberal capitalism whisper into my ear: enjoy me, resistance is futile.

Laissez-Faire, photographs by Cristiano Volk; essay by Eugenie Shinkle; 216 pages; FW:Books; 2022

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.7

If you enjoyed this review, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles and videos about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!

Ratings explained here.