“My older brother’s name was Kazumichi (一道),” Daidō Moriyama wrote in April 1982 in an essay published in Asahi Camera. “He left this world when he was only one year old. Obviously, I have no memories of him. We were twins. If we consider my brother a copy of the Moriyama family, then I am a copy of a copy. The ideogram for his name “一” (kazu, “one”) was superimposed with the ideogram for “person” (人) to form my name (大道), and I ended up surviving.” Originally, 大道 was read as Hiromichi, but the photographer later changed it to Daidō, the now well known name (Japanese ideograms can be typically read in more than one way).

The quote sits at the very beginning of the first essay included in Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective, a catalogue that accompanies a retrospective organized by Thyago Nogueira in São Paulo, a city that itself has a very large Japanese community (at the time of this writing, the exhibition is now on view at C/O Berlin). As Nogueira makes clear in his own long and well researched essay, 1982 was a pivotal year for Moriyama. Ten years earlier, he had published 写真よさようなら or Bye Bye Photography as it became known in the West.

With that book the artist had reached the logical end point of a development that included membership in the fabled collective Provoke. Bye Bye Photography destroyed the conventions of photography and set a counterpoint to what photographs were supposed to look like — according to the generation of photographers that came right before Moriyama. Where do you go, though, when you’ve done that? The book triggered a huge artistic and personal crisis for Moriyama. It would take him a decade to get out of it.

In part, dealing with his own biography in a photographic fashion provided a way out for the artist. Because of the father’s job, the family had moved countless times. Moriyama went to visit the many locations. At the same time, he drastically scaled down the many experimentations that had been prominent up until Bye Bye Photography. From now on, he would focus mainly on what he is widely known for, a form of street photography presented in his signature high-contrast black and white.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective makes it very clear that the artist was considerably more complex in his early incarnation than in the one he is now widely known for. Surrounded by and friends with avant-garde artists such as Tadanori Yokoo, Moriyama had explored a large number of ideas, many of which were inspired by Western (mostly American) artists, among them William Klein and Andy Warhol. At the same time, being embedded in the Japanese avant-garde art scene meant exposure to some of its outputs, such as in theater.

And there was the connection to the previous generation (generation here in an artistic sense); both Shōmei Tōmatsu and Eikoh Hosoe were important influences. Moriyama worked with Hosoe when Hosoe was producing his elaborately staged photographs of Yukio Mishima, work that became known as Ordeal by Roses.

As was the case for many photographers at the time, Moriyama worked on a large number of magazine assignments. These provided him with the opportunity to pursue artistic ideas with an almost immediate outlet — magazine spreads — available. In 1967, Tōmatsu assembled a number of previously unconnected magazine work into his book Nippon. The following year, Moriyama did the same to produce his very first book, Japan — A Photo Theater.

Moriyama’s book is generally not seen as a portrait of the country so much as an investigation of photography. I think that’s too simplistic a read. If you ignore the photography aspect, Japan — A Photo Theater lays open the many conflicts over what the country might be or what it might mean to be Japanese. It’s brilliant work, in part because of the fact that the different photographic approaches drive home the point in a visual fashion.

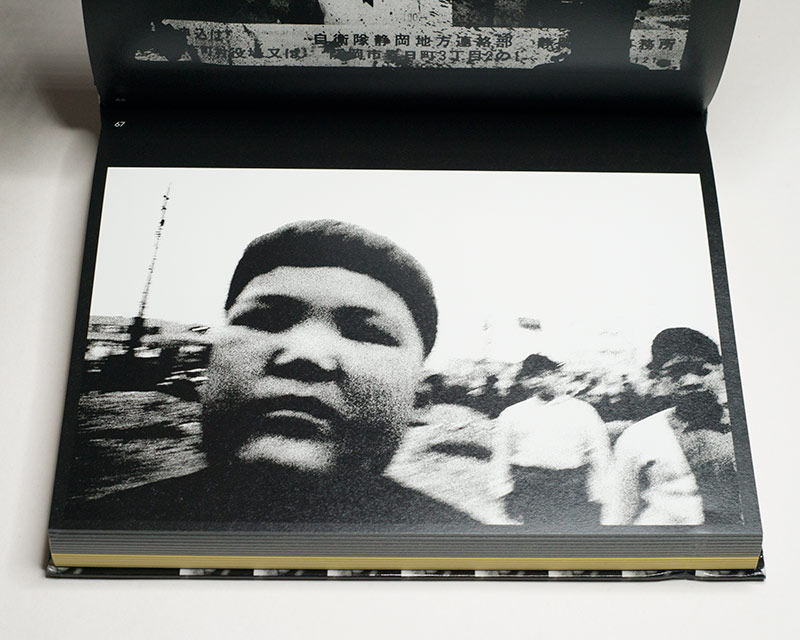

I am very familiar with Japan — A Photo Theater. I own copies of the 1995 and 2011 re-releases, both of which differ in form and printing from the original. In an interview published in Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s, Moriyama made it clear that he was interested in what photographs might look like when printed in different ways. “When I first started taking photographs,” he said, “I felt strongly that my photographs come into being via rotary press [like those high-speed printing machines used for printing newspapers]. It is for that reason that I dislike having an exhibition that is made up of photographic prints. […] An actual photographic print creates one type of world that is totally different from the world that comes about from printed matter.”

In a physical sense, this type of thinking extends the idea of the copy of the copy that he spoke of in 1982. A photograph is a copy of the world. Copies of the world are thus out in the world; they have become part of it. As the copy of a copy of the Moriyama family that he said he was, inspired by Warhol he photographed magazines or posters to create his own copies.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is filled with lavish reproductions of the artist’s most famous work. Having encountered many of the photographs in the context of his books before, seeing them in isolated fashion in the catalogue was an interesting experience for me. I suspect that the hefty black-and-white printing in the catalogue is what many of his admirers would expect to see. For sure, it works very well, making for a visceral experience.

That said, I wouldn’t necessarily want to say that I prefer it over, say, the manga-style printing used in the Kodansha versions of Moriyama’s famous books. If there’s something Moriyama has attempted to teach us, it’s that not all copies have to look exactly alike for them to be interesting. It’s the spirit of the work that matters.

A crucial aspect of the catalogue is provided by a visual index of Moriyama’s magazine work. With Thyago Nogueira’s essay providing the context and background, this index adds an invaluable element to the book. It helps understanding an artist that is (or at least was) considerably more complex than the street photographer he now is. Masako Toda’s essay sheds further light on the photographer.

Those who are interested in a lot more details about Moriyama’s very early, most fruitful period, might want to seek out Philip Charrier’s masterly The Making of a Hunter: Moriyama Daidō 1966–1972. Unfortunately, much like his long essay on Fukase (that explodes many of photoland’s beloved myths about that photographer), it’s hidden behind an academic paywall. It’s Charrier’s essay that had me first look deeper into Moriyama.

In some ways, Moriyama might be compared to the German band Kraftwerk. In a few short years, Kraftwerk produced some of the most important and influential electronic pop music, only to then get completely derailed by digital technology making its entrance. After years of silence, Kraftwerk basically became their own cover band, producing ever more overproduced spectacles of the same songs whose charm previously had been the fact that they didn’t need any spectacle.

If you’re only familiar with the work Daidō Moriyama has done since 1982, you probably have no idea of the richness and breadth of his earlier photography, vast parts of which emerged from a dialogue with a number of incredibly gifted other artists. Japan — A Photo Theater is as incredible as Bye Bye Photography, even though they’re very different books. The later work pales in comparison to the earlier one, a fact that becomes very clear in Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective. The later work is repetitive, re-producing its own themes and thus turning them into clichés. Daidō Moriyama has become his own cover band, a copy of his own copy.

I’m convinced that Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is an absolutely essential book, regardless of whether you’re interested in this artist or not. If you’re not, after having looked at it you probably will be interested. At the very least, you will have acquired a vastly expanded appreciation of Moriyama and especially the context of the Japanese photography scene in the 1960s. If you’re already a fan, it’s likely that you will have your thinking around the artist expanded.

Highly recommended.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective; ed. Thyago Nogueira; texts by Daidō Moriyama, Thyago Nogueira, Yuri Mitsuda, Masako Toda, Masashi Kohara, Yutaka Kambayashi, Satoshi Machiguchi, Kazuya Kimura; 288 pages; Prestel; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!