The world of the photobook roughly divides into two camps. The first sees the photobook as a container for photographs whose purpose it is to showcase them. The second sees the photobook as a fully fledged medium in its own right that goes beyond what photographs on their own can do.

While both camps have existed for as long as there have been photobooks (meaning pretty much ever since photography was invented), over the course of the past two decades more attention has been paid to the second camp. There had been regional pockets of a heightened awareness of the medium photobook — Japan and the Netherlands can serve as good examples, but now most of the rest of the world has been trying to catch up.

I couldn’t say that I prefer one model over the other. Some photography is served very well by what I called a “gallery show on paper” many years ago: the container model. The format itself is — let’s be honest — really boring; but if it’s done well, the photographs command enough attention for the whole package to work.

But I think the successes of the second model have raised the stakes for the whole industry. There are now so many cutting-edge publishers that what can be achieved with a photobook has become more widely known. If you’ve spent enough time looking at photobooks, you know what a good designer can do; you know of the importance of paper and good printing; you know how the binding itself can be very important.

Consequently, even if as a publisher the container model is your go-to solution, you don’t easily get away with books any longer whose format itself is boring and that look as if they had been produced with little, if any attention being paid to what they look and feel like. Whichever model you prefer, a book produced in 2022 should look and feel contemporary — and not like something straight out of the, say, the 1990s.

I had to think of all of this when Florian Bachmeier‘s In Limbo arrived in the mail, produced and published by Buchkunst Berlin, a somewhat recent addition to the world of photobook publishing. The photographs in the book were taken in Eastern Ukraine, the region that was occupied by Russian forces that *wink wink* supposedly are independent entities. Given Russia has currently amassed large numbers of weaponry at Ukraine’s border, possibly looking for yet another attack on its neighbour, the topic has now re-attracted a lot of attention.

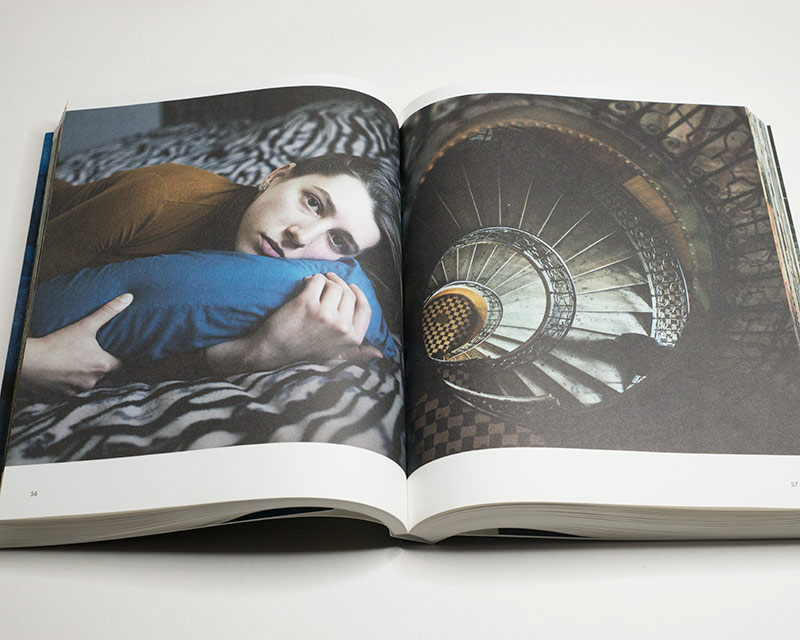

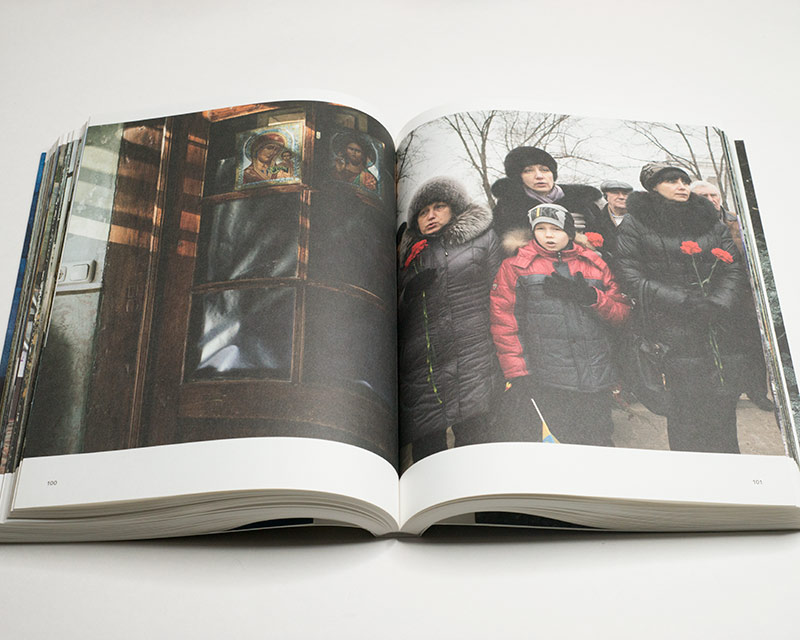

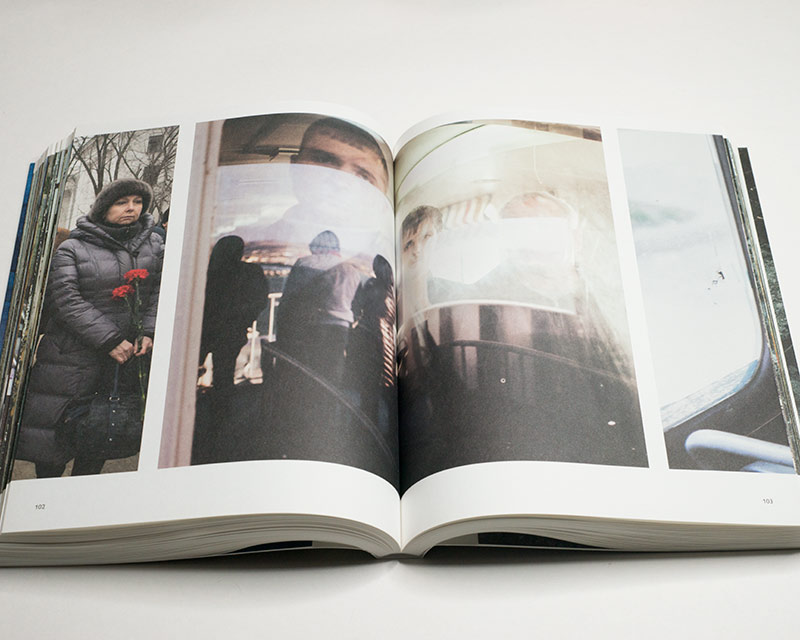

The photographs in In Limbo are photojournalistic in nature, and it would have been so tempting to produce a classical book along those lines. Thankfully, that’s not what happened. Instead, its makers decided to violate a number of cherished tenets of photojournalism. There are captions, but they’re all way in the back of the book, instead of underneath or near the photographs. What is more, a large number of photographs wrap around the book’s fore edge.

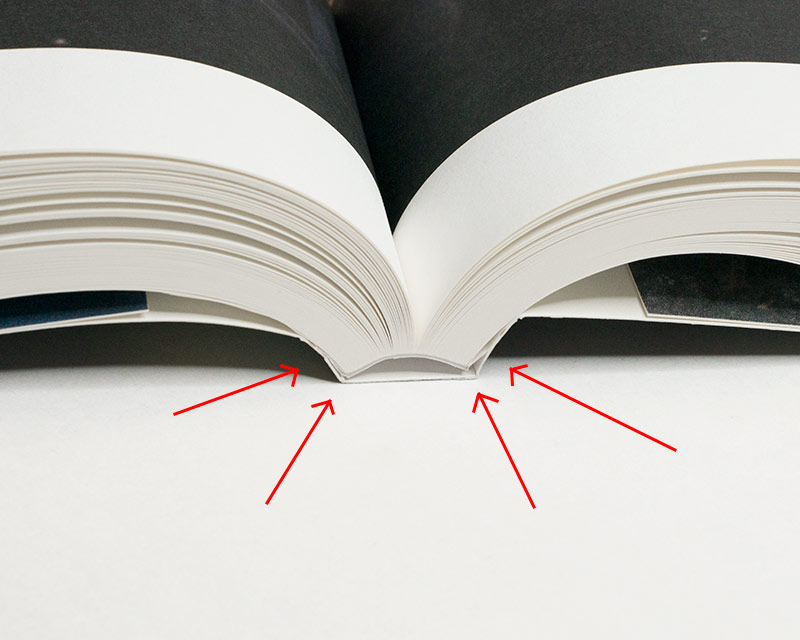

A little important production detail: note the hinged construction at the spine. This construction allows the spine of the text block to arch when the book is opened. Consequently, the book is easier to open, and the spine is less likely to crack (because there is less stress on it).

In addition, the book was printed on thin paper that was folded in half and then bound using perfect binding, resulting in what a bookbinder friend of mine told me he refers to as pouch pages. Maybe the most well known recent book that uses this technique is Rinko Kawauchi’s Illuminance (I should note that I only know the original edition and not the recent reissue).

Obviously, if you wrap photographs around the page, you essentially cut them into two pieces. This creates a problem because the two parts ideally should make at least some sense on their own. You certainly don’t want to randomly separate a photograph into two parts that each don’t work photographically. The makers of the book solved this problem very well to make sure the construct works (see the example below).

As a consequence, the viewer is taken through the book almost in a filmic way. The book propels itself forward. It’s a very effective device that creates a completely different experience than your usual photojournalistic book. In addition, the book itself — the object — is beautiful. It’s very well produced.

While Buchkunst Berlin’s books up until this one were on the very conventional side, it would seem that somehow, they decided to be a lot bolder and try something new. Good for them: the gamble is paying off handsomely.

I suspect that especially the wrapping of the photographs around the pages will cause much griping in the most conservative parts of an already pretty conservative photoland. Purists will insist on the sanctity of the photographs, claiming the device makes it impossible to see them. I would argue that the exact opposite is the case: not only does the production of In Limbo elevate the work out of that vast ocean of photojournalistic sameness, it also potentially opens up new audiences.

For sure, it had me engage with the work a lot more deeply. If this had been some generic photojournalistic book, I probably would have looked through it once. Here, I found myself coming back to the book because there is more to discover than a collection of photographic facts.

In Limbo; photographs by Florian Bachmeier; text by Kateryna Mishchenko; 180 pages; Buchkunst Berlin; 2021

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 4.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.