When it comes to their own photographs, many photographers are divas, insisting on them being treated as precious entities that ought to be treated with the utmost respect. This approach works well enough for some photographs (as exasperating as it can be to see it in action), but it ultimately does photography a big disservice. Many of the various trends we still unfortunately witness in photoland can be traced back to the precious image, whether it’s the bad mouthing or outright dismissal of what so-called amateurs produce on Instagram or whatever else.

But the precious-image approach also has repercussions inside of photoland, in particular when it comes to photographs sitting next to text. Divas don’t really like anything possibly competing with their precious images. Consequently, where text is present (often for reasons of sheer necessity), it is often treated as at best secondary, as something that more often than not doesn’t work, in fact cannot work given that much like photographs text needs to be able to do operate on its own terms. The secondary-text approach works well in a variety of contexts, such as, for example, in photojournalism where often clunky and awkward reading text serves to provide the captions or the larger context, telling everything that, alas, pictures can’t show.

Having spent the better part of the last decade writing, my relationship to text is a little different than most photographers’. But I also came to photography not as a writer or blogger but as someone who enjoyed taking pictures, and I still do. Now, whether or not I am a good writer and/or photographer is really besides the point. I will, however, make the claim that I understand the perils of both photography and writing a little bit better than many who only do one or the other.

I’m not even talking so much about how to make a good picture or write a good text, I’m talking about the psychological struggle. I do understand the precious-image approach. But I not only know that (photographer’s voice) it’s so great when things just come together in a photograph, I also know that (educator’s voice) there’s always another picture, and I know that (critic’s voice) pictures can only do so much. The reality is that photographs can come alive in a variety of ways once the insistence on the precious image falls away — if anything the recent photobook boom has demonstrated just that (the presence of the many conservative gallery-show-on-paper books notwithstanding).

Of course, to understand how photographs can work with text, looking at some cases where things work very well helps. I know that many photographers are enarmoured with Larry Sultan‘s Pictures from Home. That is a good book, but I don’t think it’s necessarily the book that reaches the full pinnacle of what images and text (or text and images) can do with each other. For that, you’d have to look at books like, for example, John Berger and Jean Mohr‘s A Seventh Man or at W.G. Sebald‘s Austerlitz. The use of photography in these two books is very different, but in both cases they contribute to the overall book immensely. Crucially, while you could easily show Sultan’s pictures without any of the text, for A Seventh Man or especially Austerlitz that would just be an absurd idea.

So for images to work well with text, I want to claim that they have to fully shed their precious-picture aspect. This is not to say that they simply have to be shitty. That’s really not the point. They need to be good pictures. But the moment they come alive next to text, they cannot insist on being precious any longer. They need to be content with operating alongside text — or rather their maker has to.

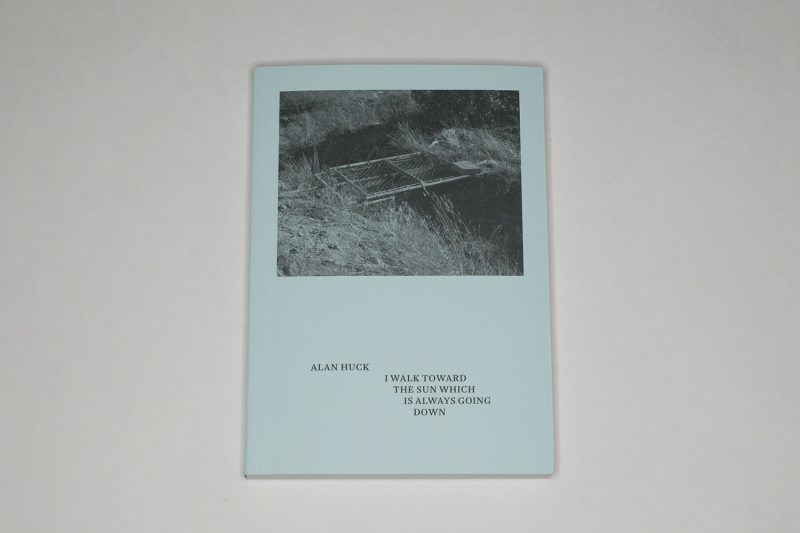

A new benchmark achievement of what the combination of images and text can achieve is now being made available in the form of Alan Huck‘s I walk toward the sun which is always going down (full disclosure: I was Alan’s grad-school advisor when he worked on the book). It contains ample text, which of course will have to be read. So strictly speaking this isn’t even a photobook — it’s basically a form of literature that uses photography prominently (I’ll leave it to academics to argue over whether or not that is a photobook).

References and/or quotations abound, both in the text and in the photographs. In the writing, the quotations can be found more easily than in the images; but they are very apparent in the photographs as well. The author thus betrays his being deeply embedded in a literary and photographic tradition. In part, the book is thus a form of synthesis where all these influences are being brought together to form a meditation on what it means to take in the world on a long walk.

On the other hand, there also exists a clear voice of its own — I walk toward the sun is not merely a collage. That voice is one that I’d describe as one of resignation, even though that’s maybe too strong a word for what’s going on in the book. Maybe melancholy would describe the mood more clearly.

I’ve read the book many times (in all kinds of iterations, including its earliest ones), and I still don’t tire of it. Each repeated reading/viewing has brought out new elements, has made me see things in a different way. I can only hope that I walk toward the sun which is always going down will find the wide audience that I think it deserves. The world of books working with text and images has just become a lot richer.

Highly recommended.

I walk toward the sun which is always going down; text and photographs by Alan Huck; 144 pages; MACK; 2019