“I grew up biracial in Capistrano Beach,” Gabriella Angotti-Jones writes in I Just Wanna Surf, “a beach town in southern Orange County in California. […] My dad’s Black and my mom’s Italian. […] The only Black people I saw every day were my sisters, and my dad when he was home. There were no other Black families in my immediate neighborhood.” Surfing plays a large part in the area, and she became a surfer as well. But “I didn’t feel like a surfer,” Angotti-Jones notes, “because I didn’t fit the stereotype.”

I can’t claim to know anything about surfing other than that stereotype. If I Just Wanna Surf has taught me something it’s that there is a lot more than the stereotype — even as various aspects of it are quite pronounced. “There’s a macho culture in watersports,” the book tells me later, “where if you can’t do it or if you can’t handle it, you shouldn’t do it.”

Seen that way, surfing appears not to be that dissimilar than a lot of other human activities (hello, photography): “One of the reasons surfers are infamous gatekeepers is because lots of people pretend to be about the lifestyle and wholesomeness, but they really don’t respect the process or its roots.”

I Just Wanna Surf centers on more things than just one, making it one of the most unexpected recent photobook experiences for me. On top of the surfing and being Black and being a woman, there also is a mental-health struggle. It’s a lot, and it’s being navigated deftly in the book. For Angotti-Jones, this is her life and her attempt at navigating all its various aspects while trying to assert herself, embracing the frequent joy that can be had.

“I always wondered,” she writes, “if being in the ocean felt like what it’s like to be White. No worries, nothing to really think about — just vibes.”

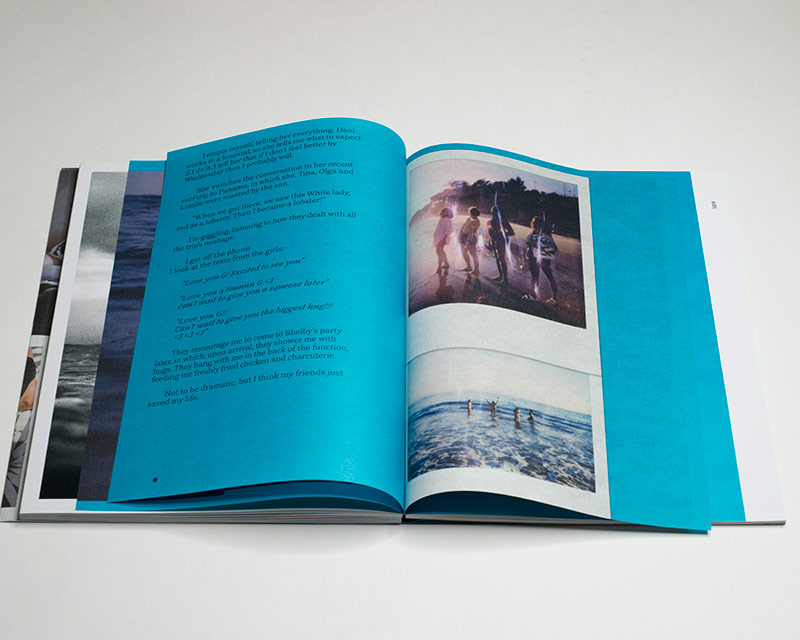

When I first saw the book’s pictures, they were lying on a large table in the form of cheap prints. There were so many, taken with a variety of cameras. They spoke very clearly of the joy of the small community of Black women surfers that Angotti-Jones belongs to. At the time, I couldn’t quite imagine how they would form a book.

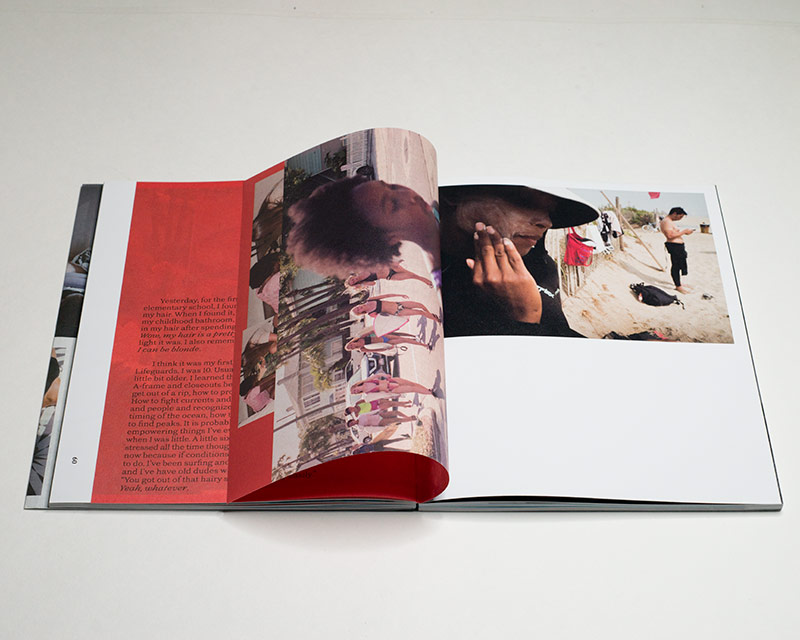

Months later, there is the book, and it works so well. It narrates the story through a number of sections (they’re not strictly delineated or separated as chapters), into which blocks of text have been set. The text serves to introduce the many aspects of the book that no picture could fully tell.

There is a picture of a group of young women walking to a beach with surfboards, two Black women in front, following by three Whites one. What they might be thinking or feeling the picture can’t convey. But the text can. In contrast, the joy and excitement felt when being on the beach or in or on the water is communicated most strongly through the pictures.

It’s this give and take between text and photographs that is being navigated deftly in I Just Wanna Surf. Bringing text and images together means having them dance together so that one won’t diminish the other. This works very well here.

It works very well because both with her camera and her words Angotti-Jones is an extremely gifted, passionate narrator. Being close to the material (terrible word, I know) of course helps. But being close also means that everything feels so much more loaded, so much more revealing. I obviously don’t know to what extent this applied in this particular case. But as someone who has struggled with depression for a long time I know that I would be rather hesitant to make it part of my work (even if I knew that omitting it would cut an important part of the story).

I can only applaud Gabriella Angotti-Jones for being willing to offer all of it to us as viewers and readers. Some stories not only need to be told because they are outside of what we take for granted. They also need to be told so that as an audience we can experience how liberating making a deeply personal photobook can be. It’s a different experience for maker and audience. But I believe that the ultimate lesson is shared: allowing oneself to be vulnerable only leads to personal strength.

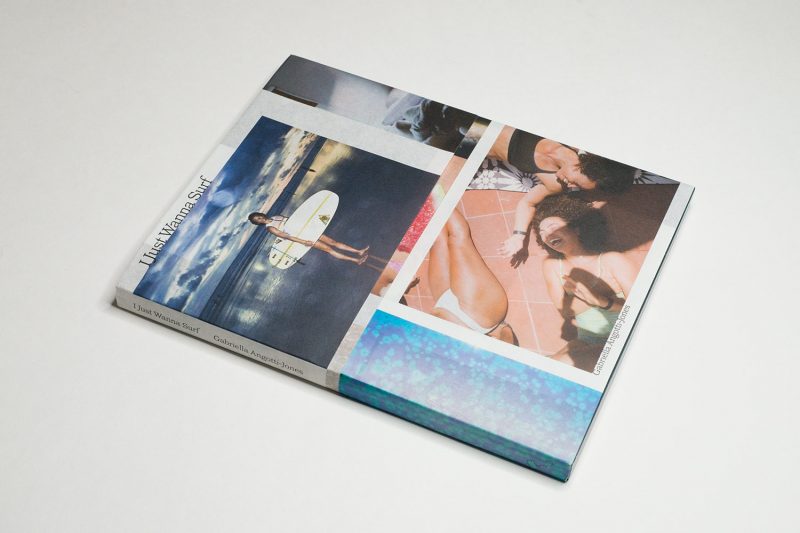

Mass Books, the publisher, once again employed the help of Dutch design and production. Yet again, this has paid off handsomely. The book manages to strike that delicate balance between not being a precious art book while using all the various tricks such a book might use.

The production is impeccable and does much to help the book communicate its message. There are two paper stocks, with one being predominantly used for the bulk (but not all of) the text. The design helps to organize the material (and text) while at the same time keeping the infectious spirit of the photographs alive. I’m sure the more conservative segments of photoland will bemoan some of the choices. But a less daring book would have simply been too boring for the spirit of the work.

You could easily take I Just Wanna Surf as a prime example of what the contemporary photobook can achieve. It demonstrates the beauty of text working with photographs, it covers a variety of important cultural and societal issues all the while focusing on an individual navigating them, it shows how design and production can serve to organize and elevate the material, and it’s a huge source of joy for its viewers.

Highly recommended.

I Just Wanna Surf; photographs and text by Gabriella Angotti-Jones; 148 pages; Mass Books; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!