Laura Mulvey’s seminal 1975 Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema defined what is now known as the male gaze. In a nutshell, the term describes the world — men, women, everything else — being viewed through heterosexual male eyes. This approach creates all kinds of problems, in particular women getting reduced to both sexual objects when they’re being viewed (in a film) and to passive observers when viewing (a film). Consequently, the male gaze is a lot easier to detect when you’re at its receiving end, when, in other words, you’re not a heterosexual male (if you are one, the film world basically looks like the world you’re familiar with — note this needn’t be approached only in a literal sense: superhero movies, for example, clearly are completely fictional, but their use of the power dynamics between the genders in all likelihood is not).

The male gaze obviously has applications in the world of photography as well. These applications concern both the way photographs are being taken (and by whom they’re being taken), but also the way in which they are being embedded in the various contexts they’re part of (and by the people doing that). There has been a growing awareness of this issue. See, for example, discussions of gender inequality in photojournalism and the many reports of sexual harassment: this 2018 article by Kainaz Amaria is all you need to read to learn more about the topic.

Out of curiosity, in mid 2018 I compiled statistics of the photobooks featured in the first two volumes of Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s The Photobook: A History. The numbers paint a grim picture. Of the books discussed in Volume 1 (Volume 2), 191 (174) are by male authors and 18 (37) are by female authors. Please note that I counted the books once, so there might be counting errors. Also note that I counted each book listed, so some artists are represented by more than one book. Specifically, in the case of Volume 2, there are 11 books by Roni Horn, which somewhat inflates the already low number of books by female authors.

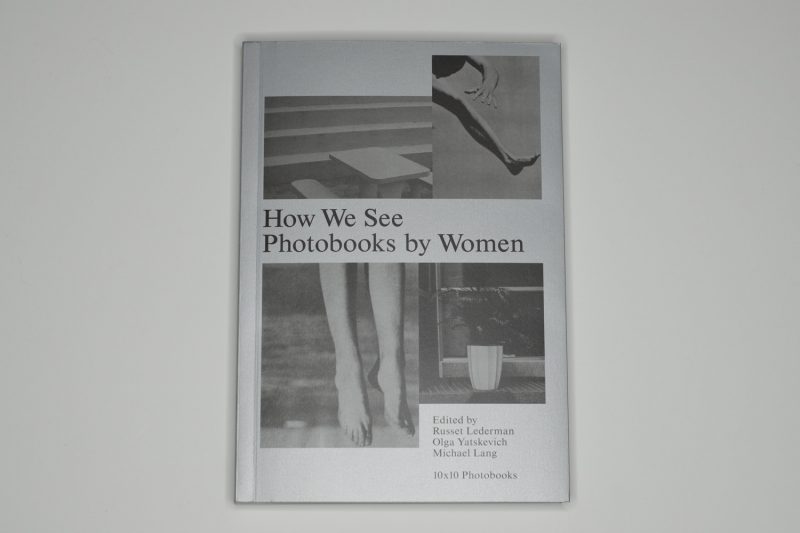

Perhaps not surprisingly, How We See: Photobooks by Women starts out with a list of similar statistics. For example, books by female authors account for 16.2% of publishers’ titles or for 22.9% of shortlists in the various “best of” award or year-end lists. The selection of books assembled by editors Russet Lederman, Olga Yatskevich, and Michael Lang is thus overdue.

The structure of the book follows the model used earlier by the same editors. A group of ten selectors was picked to cover their respective geographic regions, each selecting ten books. There’s an introduction for each selector, and the books are then briefly introduced on a spread with a picture of the book’s cover, a very short text, and a few sample spreads. In addition, there are a few essays in the beginning. At the very end another group of selectors, mostly curators and photo historians, provide a list of historical books.

I’ve heard stories of the lists of books covered in Parr/Badger being distributed before the books came out so that people would be able to get the books before the inevitable rush to buy them would set in (I have more than one source). I don’t know if a similar rush has already set in for the books covered in How We See. The part of me that finds the whole secondary photobook market distasteful hopes that’s not the case — after all, good books should be easily and widely available instead of being items for (mostly rich) collectors.

But the rest of me is hoping that there is indeed going to be such a rush — just not by the usual collectors, but by photoland in general. There aren’t just the statistics given in the book; a quick glance at the result of the 2018 Photobook Listmas (at the time of this writing [31 Dec 2018], that’s “705 books that were listed as the best, the most interesting, relevant, notable, exceptional and/or favourite books by 248 different people/institutions on 107 lists”) shows that photobooks by female authors still are underrepresented, are underseen, if not straight out unseen.

How We See makes a strong case for many books that so far have been overlooked or neglected. For example, there are multiple books by Sophie Calle included, who I think is an exceptionally strong artist and who also is an artist that I yet have to see mentioned in discussions of text and pictures (to give just one example). There’s Abigail Heyman‘s fantastic Growing Up Female, which not only is as timely as when it was produced but which also has very strong lessons to offer for students wanting to learn about editing and sequencing or (again) the role of text next to photographs. And the list goes on and on.

With its geographic focus, there are plenty of books from areas that you simply will not find in other books about the subject, whether they’re from Africa, parts of Asia… The selectors also picked books based on their own preferences and interests. This might strike the reader as an obvious fact, but it is clearly acknowledged in the book — as it probably should be.

So if you are interested in photobooks, I don’t think there’s a way around getting yourself a copy of How We See: Photobooks by Women. It’s not only a must-have addition to the world of books about photobooks. It also is going to become an essential part of a larger, long overdue discussion in photoland about who gets to make the pictures, who the pictures are of, and who gets to see them.

How We See: Photobooks by Women; edited by Russet Lederman, Olga Yatskevich, Michael Lang; 305 pages; 10×10 Photobooks; 2018