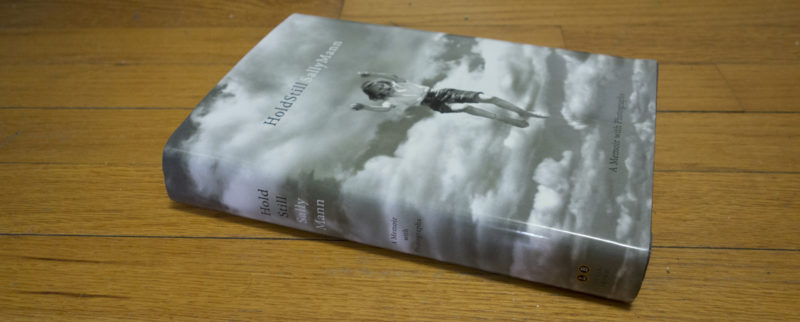

The subtitle of Sally Mann‘s Hold Still is given as A Memoir with Photographs, which it well might be, depending on how you flexible you want to be with the term “memoir.” I’d say that the book is in part that, a memoir, and in other parts, it’s clearly not. Your enjoyment of the book will depend on how closely you will stick to the idea of memoir. Another part of your enjoyment will probably be determined by how closely you’d like the book to remain to what is probably going to get many, if not most people interested in the book in the first place, Mann’s photographs.

I feel compelled to preface this review with the above because I didn’t really think too much about any of it before reading the book, and I ended up feeling I got more than I probably subconsciously asked for, and less. I’ve been trying to find out whether the more outweighs the less (I don’t think it does for me), and I’ve also been trying to find out whether that’s just based on my own expectations (it’s very possible).

It’s rather safe to say that Sally Mann is one of the United States’ preeminent photographers. As those reading the book will find out, she also is an immensely gifted writer, which certainly is not a given at all when one deals with photographers. I don’t know this for a fact, but I have the feeling that Mann would scoff at the idea that as a photographer, you simply can’t write, an idea that, sadly, is being peddled way too ubiquitously. Between Robert Adams and, now, Sally Mann, it might be time to retire this idea.

Hold Still clearly is a memoir as far as parts of Mann’s life are concerned. The reader is given ample insight into her childhood and adolescence up until the point of marriage. Beyond that, however, I’m not sure the word memoir applies all that well. What happened during the making of those photographs that made Mann famous (her family work), say, is largely left out of the book, a few crumbs here and there notwithstanding.

Instead, the reader is provided with a lot of detail of the author’s family, going back generations. As someone writing a memoir is wont to be doing, Mann detects traces of her own personality in those that came before her. There also is a larger chapter on race, which uses an African-American woman employed by Mann’s father as a nanny as the spring board. Of course, this chapter plays off against the overall background of the American South, which in itself features prominently in the book.

What I was mostly interested in, I realized after having finished reading the book, was whether or not it helped me see Mann’s photographs more closely. I’m not sure it did. Three larger sections stuck in my mind. While the family photographs are clearly acknowledged, their making for the most part remains in the dark (there is a short discussion of one of the pictures, including outtakes, though). But considerable space is given to a description of Mann’s reaction to the reception of the work in the early 1990s.

I very much do appreciate that the photographer would defend her work as forcefully as she does in the book. There is not much more you can ask than the following: “How can a sentient person of the modern age mistake photography for reality?” (p. 151) But then, that’s what people do. Your task — the photographer’s, the author’s, the critic’s, … — is to help people see how and why that is in fact not the case, how photographs are an reality (their own), but not the reality of what they purport to depict.

I think Mann could have bolstered her case by discussing the making in more detail other than, for example, talking about the great light in one picture. She is too smart a photographer to have me even remotely believe all she’s interested in is the light. What is more, later in the book she does talk about portraiture in ways that make it sound as if she did in fact herself mistake photography for reality. This is not to say that I don’t buy her defense — I do; but I also feel if anyone could have made a unique, stronger case, it is her.

There is another large section on the photographs that became Deep South, which, full disclosure, I think are the weakest pictures in Mann’s otherwise impressive oevre. The prose in Hold Still largely is very eloquent and witty. But in the sections on the South (and its photographs), things get a bit too baroque for this north German turned New Englander. At times, I found myself wishing the editor would have firmly put both feet on the brakes, given some of the metaphors in the chapter on the South are running amok, and not necessarily in a good way. What we love the most, we ought to love the most. I know that very well. But when expressing with words what we love the most, restraint, but not reckless abandon, makes for a wise companion.

Another larger section deals with the photographs at a body farm, which those who watched the documentary What Remains will be familiar with.

While some of the well-known male peers in Mann’s age group have made careers out of sticking a camera into people’s faces while roaming the streets or shallowly mocking the obvious in oversaturated ways, this particular photographer has demonstrated why and how a photographer can indeed become an artist: by embracing the possibility of failure, yet pushing her own vision forward, and by not being content with what can be easily had. Ultimately, it’s about the “what could be,” which in equal amounts is the expression of a deeper instinct (which all the prose in the book notwithstanding is inexpressible) and of an openness to seeing what can be found.

Hold Still deserves to be read widely in photography circles, given it offers new facets of a photographer who has been relentlessly pushing her work for decades. Much like Mann’s photographs themselves, the book is very good, at times brilliant, at times a bit flawed. This is, after all, what makes good art good: it is made by human beings.

Sally Mann: Hold Still (A Memoir with Photographs); 496 pages; Little, Brown and Company; 2015