I can’t look at 家族 (kazoku – family) without my ideas of family in mind, in particular my tortured relationship to some of its members. To pretend that I could look at these photographs of a father-son relationship without any of that weight would be a travesty.

•

I’m intensely drawn to these photographs as much as I am revulsed by aspects of many of them. I’m tempted to think that this is what makes good photographs. But I will admit that having thought about this idea for a while I’m not so sure any longer. It is, however, what makes photography interesting for me.

•

I don’t believe for a moment that the pictures in the book are a project in anything other than the loosest sense. I never believed this, even without knowing the dates of the pictures. As much as I have been enjoying seeing them, they always struck me as fragmented. Maybe that fragmentation gets at a larger truth of family.

•

Various of these photographs contain elements of cruelty. Whatever you might think of Masahisa Fukase, I will deny that you can think of him without such an element of cruelty. I’m somewhat tempted to think that I understand part of the impetus that might have produced the (photographic) cruelty, but I am not willing to accept this interpretation as an excuse. As a photographer, I don’t think I could employ my own cruelty to make pictures. This might make me a bad photographer (in the eyes of those who cherish seeing cruelty in pictures), but that’s a price I’m willing to happily pay – both as a photographer and (first and foremost) as a human being.

•

•

That said, the photograph of Fukase and his clearly ailing father (plate 29) is a masterpiece. It is cruel. The old man looks terribly frail, while the younger man’s gaze appears to cherish the power he is being granted by the camera and also by his father who has submitted to that. The submission could have arisen in a variety of ways – we have no way of knowing. The old man was a studio photographer for many years, and I’m refusing to believe that the knowledge of what a camera can do would have left his mind completely by the time the picture was taken. There is a slight smile in his expression – maybe a hint of that knowledge/acknowledgement. Fukase’s essay informs me that back in the day, he was well known for his ability to “prettify his shots, to straighten people’s noses, firm up their mouths and level up their shoulders”. That is a form of benevolent cruelty – make people see themselves in their pictures the way nobody would see them in real life (the fact that in a society such as Japan’s nobody would say this doesn’t change a thing). There’s more to the picture, though, given it’s just the father and son, surrounded by nobody else: there’s just so much space around them: They’re close, and they aren’t. They’re separated by so much.

•

“I was terrified of my father as a child. He had an extremely short temper, and he would fly into rages at the slightest thing.” (Masahisa Fukase, afterword to 家族, p. 85f. in this MACK reissue)

•

Coming back to that picture (plate 29), the cruelty isn’t so much the depiction of the frail man’s body, it’s the posture and the knowing glance by the son holding his father, holding his frail father in place. The old man is made to sit. I didn’t know this when I first looked at the picture, but when I read what Fukase wrote about his relationship to his father as a child it all made perfect sense. This photograph is some serious pay back.

•

Speaking of pay back – in advance or as you go, of the various female props used by Fukase, his wife Yōko stands out the most. In the larger-group pictures, her place is at the left side, at the edge, and much like her peers, she is allowed to only wear what I learned is a traditional undergarment for women (koshimaki). In effect, she is naked, and it is only said garment and her long flowing hair that allows for some form of modesty. Her gaze is very confrontational in the way the gazes of all the other extra women are not. Even in the picture with her husband (plate 23) she looks very unhappy. If someone had told me that she would divorce her husband after I had seen the pictures I would have totally believed it. Truth be told, I knew that she did just that, but I only learned about her identity in those pictures from the captions. So there’s more cruelty – in all the photographs of the extras, it’s only the wife (ex-wife when the book was originally published) that looks profoundly discontented.

•

Fukase “once drunkenly stabbed Yōko in the back with a kitchen knife.” (Philip Charrier — ‘Becoming a Raven’: Self-Representation, Narration, and Metaphor in Fukase Masahisa’s ‘Karasu’ Photographs, Japanese Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2. September 2009, p.219)

•

Coming back to why I don’t believe that this was in fact a project: it doesn’t feel like one. It feels like pictures of convenience, albeit a convenience that was very inconvenient in the moment when each picture was taken. The dates from the book support my idea. Nineteen seventy one, 72, 74, a huge gap, 85… This is just too convenient. The 1985 ones would almost seem like an idea picked back up from ten years earlier. This is not to invalidate the idea of the book; it’s just that I don’t buy Fukase’s packaging.

•

•

The variations on the themes, the different family photographs have me engaged. There clearly is the idea of exploding the boundaries of the official, expected studio photograph through the addition of elements alien to it, whether it’s the dress (or lack thereof) of the extras or their behaviour. The naked young woman striking a ridiculous pose from 1972 (plate 9 – she is referred to as “K., an actor”) is the most extreme example and possibly the most failing one. There is the question of how much is too much, how much, in other words, one would have to break through and out of the conventions of what an official family portrait might look like. In a sense, having that added visitor might be enough, but then in all cases it’s a young (attractive) woman, and does one really need that kind of device? I’m not sure.

•

“In 1973 an exasperated Yōko wrote about Fukase’s dramatic mood swings in Camera Mainichi and said that he inhabited a kind of personal hell which made it impossible for him to see beyond himself.” (Charrier, p.220)

•

The following statement by Michiko Kasahara, at the time Chief Curator at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, easily applies to Fukase as well: ‘For better or worse, we are able to glimpse the Showa-period male’s concept of women and view on life and death running throughout Araki’s body of work.” (Michiko Kasahara — Captive Araki, in: Araki Nobuyoshi — Sentimental Journey 1971-2017-, HeHe, 2017, p.255)

•

•

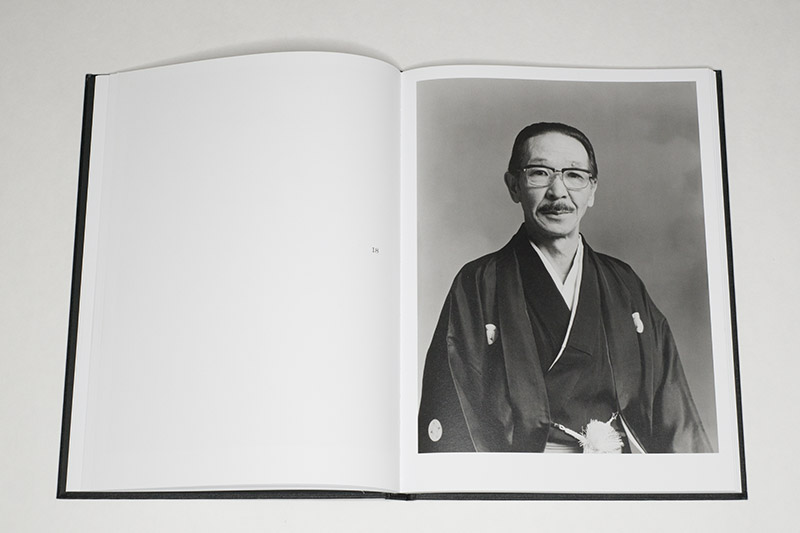

Two plates (18 and 19) stand out in that they feel very different. Well, they are very different. They were made by Fukase as i-ei, as photographs to be used at the sitter’s funerals (a Japanese custom). One (18), the one of the father, does indeed appear later (in plates 32 and 33), much like another such photograph (probably not taken by Fukase) does, one of a young girl, a niece of the photographer’s, who died aged 5. These i-ei and their uses are interesting in a variety of ways: they speak of what some photographs mean for us as human beings.

•

However much the sitters are made to clown around in the pictures, the young girl’s i-ei always faces the camera. It is as if Fukase knew some boundaries after all — or maybe it is merely that his connection to his niece was very loose, with very little emotional attachment.

•

“When I work I’m wishing that I could stop this world. This act [of photography] may represent my own revenge play against life, and perhaps that is what I enjoy the most.” (Fukase in Camera Mainichi, 1976, quoted in Charrier, p.227)

•

In the penultimate picture in the book, the final family portrait (plate 33), it is telling how much Fukase ended up physically resembling his father, much more so than his brother (who is holding the father’s i-ei above their mother).

•

Maybe what attracts me to this body of work, to this book, is that it resists the kind of resolution of so many other family projects where differences are acknowledged, and people might go their own ways, but it’s all good. Often enough, life just will not conform. Here, that narrative is missing, and there is just an assembly of fragmented ideas and aspects, some which are fighting each other. This is good. This is interesting. I’m almost glad that there is this gap of ten years in the book, because if it had been somehow filled out (making this a real “project”, let’s say in the sense used at art schools) the whole might have become so much less. Sometimes, it’s good when things are not too spelled out.

•

Does plate 22 (1974) show Fukase’s own i-ei? I’m thinking yes and no. Yes for the self-absorption Yōko wrote about the year before, and no because while the dress looks at least somewhat formal to me, it is not quite as elegant as the one worn by his parents. There is what looks like a stain on the collar. Two years earlier, Fukase had written in Camera Mainichi that “these photographs were a ‘parody’, taken by ‘myself, the third-generation son, the loser'” (Tomo Kasuga, Archiving Death: The Family Portrait as a site of Mourning, p.90 in this MACK reissue). So the no becomes a yes? Does plate 22 show the photographer’s narcissism gone haywire?

•

For her earliest work, Yurie Nagashima was to create photographs along the lines of plate 17, except that there, the family members would be completely naked, they’d be in their home, and there’d be no stranger added. I’m liking both group images equally. However, the grim determination of the Nagashimas wins me over more than the more deadpan studio setting of the Fukases (plus guest). Yurie Nagashima’s shaved head strikes me as the more radical gesture than the addition of the guest actress in Fukase’s studio (maybe it is my knowing of the female photographer’s feminism that is making me feel a little bit guilty over even comparing these two pictures).

•

I feel like one can’t do a family project any longer without considering 家族, whatever conclusions one might arrive at. I’ve recently been spending some time with Kaitlin Maxwell‘s photographs, the ones called Current Series on her website. I’d love to see it as a book, and I’d then love to have that book and Fukase’s next to each other to see what that would teach me. Obviously, the types of photography are very different. But there are overlapping themes, such as what photographs can tell us about families, and what happens when a photographer decides to place her or himself into the pictures (which, truth be told, I always thought Doug Dubois should have done).

•

I suppose what I’m trying to say with the preceding is that it’s fine to photograph your family, but there will have to be something at stake for you, the photographer (“Show Your Wound” — Joseph Beuys). I don’t know if Fukase knew that there was something at stake for him. It’s possible, albeit not likely, assuming that the aforementioned statement about the personal hell he was living in was correct (and why would it not?). But whether he knew or not doesn’t really matter for us, the viewers, because we can see for ourselves. And we should have a good, hard look at these pictures, because they can teach us a lot about ourselves.

Family; photographs and text by Masahisa Fukase; essay by Tomo Kasuga; 80 pages; MACK; 2019