Whoever came up with the title of Fünf Finger Föhn Frisur did a marvelous job, and kudos to the publisher for not translating it. The book’s main essay is reproduced in its original German (Frisurwandel der Öffentlichkeit) and in English (The Structural Transformation of Hair in the Public Sphere) — oh, the beauty of the German language! But who needs text anyway when one can enjoy what look like (and are) promotional photographs made for a Zürich based hair salon from the 1970s until the 1990s?

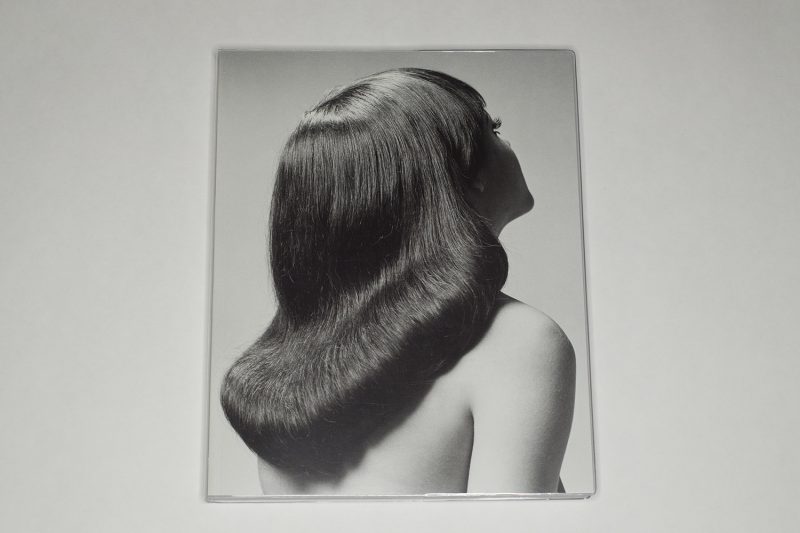

For better or worse (your choice), Fünf Finger Föhn Frisur is a book about sculpture, more precisely the kinds of sculptures created on the heads of upper-class bourgeois Zürich women that a strong gust of wind outside might have easily transformed into something a little less impressive.

I must have grown up being exposed to similar photographs (no upper class, no Zürich) when I went to the barber, but of course, I didn’t pay any attention to the photographs on display, what with my general dislike of getting my own hair cut. In hindsight, there are at least two regrettable aspects to this fact, namely a) the rather bad hair cut I liked (oh boy!) and b) my missing out on enjoying the photographs I could have taken in instead of ignored.

But that’s how it goes, doesn’t it? We ignore what is all around us, only to later engage in perhaps slightly exaggerated swooning when presented with what we missed out on. There always is the danger that a form of nostalgia is being created that stands in no relation to the actual merits of the things or times in question. The other danger is things or people being exoticized which can easily create a form of othering. So I’m always a bit wary about photobooks that present collections of old pictures. It’s hard to say what the recipe is to avoid these pitfalls — or whether there even can be such a recipe.

As far as I can see, there is no nostalgia here, though, except maybe for the production of these photographs. For sure, nobody is being exoticized here, either. What exactly is going on here? This is where it gets interesting for me. I personally have no interest in hair styles (anyone who has ever met me in person will not be surprised by this statement). Most of what is depicted in the book strikes me as a bit dated, but I’m not 100% sure. Now, if I were interested in hair styles, I’d probably look at the book as that, a collection of them that I might find interesting or revolting or whatever else; but that would be a lot less interesting than what I’m facing here.

When I wrote above that there’s no exoticizing going on, then that’s maybe not entirely correct. For me, much of what I encounter is exotic, but it’s a form of being everyday-exotic: something that is very familiar in some ways, that is thus not being paid much attention to, and that then takes on a very different and fascinating character when it becomes the center of attention. This has me fascinated. Of course, this is something that someone who is paying a lot of attention to hair styles might not experience.

But the paying attention to these pictures throws their artifice into stark contrast. That artifice actually splits into two parts. There is the artifice of the hair styles, which seems to follows its own logic (rather the logic of, say, ease of use or whatever there might be). And there is the artifice of the photography, with its often strange (or maybe I should say strangely exaggerated) poses, the way it often dissolves the figure below the shoulders, and its often just too exaggerated ideas of seduction: the smiles are just a tad too fake, there might be too much of a faux-erotic squint going on — or its opposite, etc. It’s all photographed so well that none of this falls apart. The phoniness is almost believable. Almost. That makes it interesting.

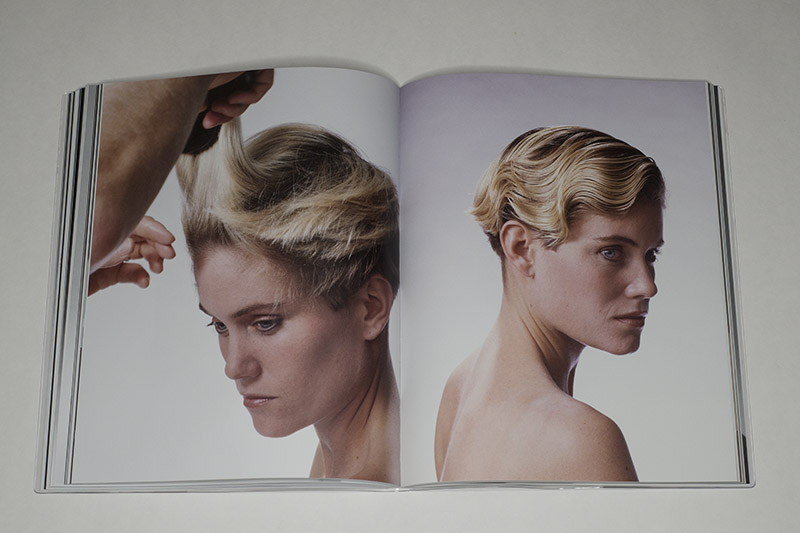

With its inclusion of behind-the-scenes material — invoices, contact sheets, etc. — Fünf Finger Föhn Frisur keeps reminding the viewer of the production, of the artifice involved. What’s more, in various cases different versions of a photograph are included. This way, the book always centers on the photography as much as on the sculpted hair.

Ultimately, the book asks of us to pay closer attention to the photography we see all around us, whatever context it might be embedded in. Ultimately, photography used in advertizing can be just as revealing and interesting as photography in an art museum. Often enough, it’s just as well (or even better) produced. Its ultimate purpose might be different — but why should one type of manipulation be worse than another?

Fünf Finger Föhn Frisur; photographs by Gaechter+Clahsen; essay by Jörg Scheller; Edition Patrick Frey; 2019

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.