“Hundreds of thousands of people have fled across the Mediterranean Sea this year to escape war and persecution,” the UN Refugee Agency UNHCR wrote at the end of 2015. Two of the key events listed in the article have now resulted in photobooks.

In early September that year, after thousands of refugees decided to walk from Hungary to Germany, things accelerated very quickly, with Germany accepting over one million of them (please note that while the use of the word “refugee” in this context is contested — see some details here, I decided to stick with it, given it’s the term used in the UNHCR article).

As you can imagine, accommodating over a million people would strain the resources of any country. In what now can be considered the long term, Germany did very well; but of course the lived reality of all those who arrived with next to nothing varied considerably. A group of young men ended up in a former guesthouse in the Black Forest, located far from the next village and shopping facility.

Black Forest — that might sound nice, unless you imagine being stuck there in the legal limbo that German authorities only slowly managed to lift. “The mills of justice,” a German saying goes, “grind slowly” — and let’s not even get into discussing what’s contained in that term, justice. How do you even deal with such justice, which might insist in all kinds of paperwork, when all you have with your are the clothes on your body and, possibly, a few possessions? How can you prove anything in a country whose culture (if that’s the word) relies on requires written proof, usually in notarised form?

What do you do with your spare time (of which you have a lot), given you’re not allowed to work and the next village is far away, when you’re confined to what actually is a pretty shitty dump?

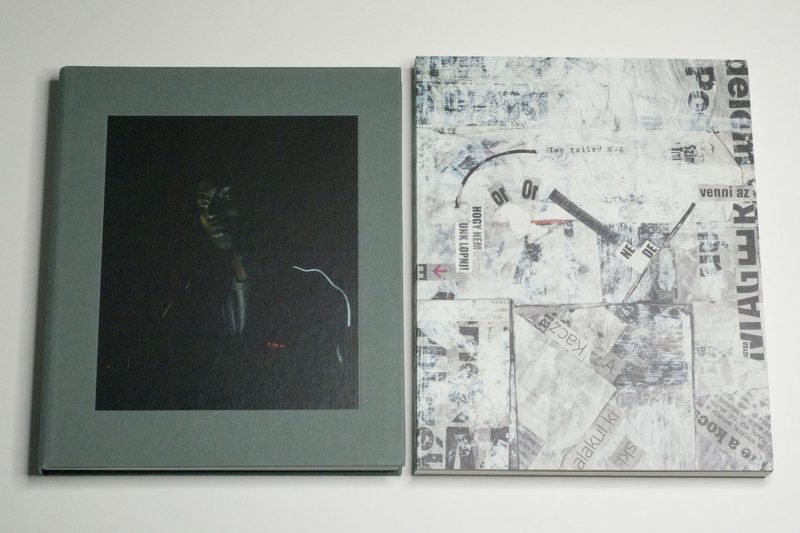

These questions sit at the center of Holzbachtal, nothing, nothing, a book by Berlin based photographer Sibylle Fendt. Over the course of a few years, Fendt drove to the shelter to spend time with the men. “I spent hours, days and weeks there,” she writes, “without anything happening. […] Usually, I was welcome, I was often invited to dinner and was allowed to pass the time in their company. Every so often however […] they wanted to be alone.” (quoted from the book’s brief afterword)

In a sense, the book is completely devoid of a story — what would be the story of “nothing”, of waiting endlessly for something to finally happen? How can you make “nothing” the story, in particular in and with photographs?

Fendt solved the problem the way any photographer would do it: by photographing the inhabitants of the shelter while they were going about their business of spending time until the moment when something happens. Phones provided a window out into the world, and where young men gather with nothing else to do, inevitably there will be weights to be lifted.

The (mental) proximity Fendt established with the men clearly comes across in their photos, whether they’re portraits or pictures of them doing something. In between, there are photographs of parts of the house, which was little more than a grimy mess — a mess one would imagine many of their peers would have also found themselves in after their arrival in one of the richest countries of the world (to imagine that some right-wing dipshit would inevitably complain about how good these refugees had/have it makes one’s blood boil).

A view towards the Black Forest from the same vantage position at various times of the day and year serves as the book’s introduction. Time somehow passes even as that passage of time does not appear to result in any meaningful change for the better. Maybe now that we’ve all gone through living under the pandemic, we have all caught a glimpse of what it might be like to wait somewhere for something better (obviously, unlike these refugees, we have had all our creature comforts while we were or are in lockdown).

I’m always hoping that getting a real glimpse of someone else’s suffering might make us better people. But we already know from history that that’s probably not going to happen. Why then even bother photographing or making books like Holzbachtal, nothing, nothing? Because doing nothing is an even worse option. I’m here speaking for myself and not for Sibylle Fendt. I have known her for quite some time now, and I’m thinking she might be more optimistic. Either way, here’s a book about the ongoing refugee/migrant crisis in Europe.

Meanwhile, in Hungary, the country whose opening of the borders with Austria (literally a cutting of holes into a fence) accelerated the collapse of the East German communist regime, its autocratic leader Viktor Orbán built a new border fence, ostensibly to keep refugees out, but also to drum up even more support for his utterly corrupt regime.

The European Union has now started to look into the corruption, causing Orbán to rail against the organisation that his country decided to join. It’s not even that the EU minds a violation of the rules all countries agreed to abide by, it’s also not clear why European citizens should essentially pay to line Orbán’s and his allied oligarchs’ pockets.

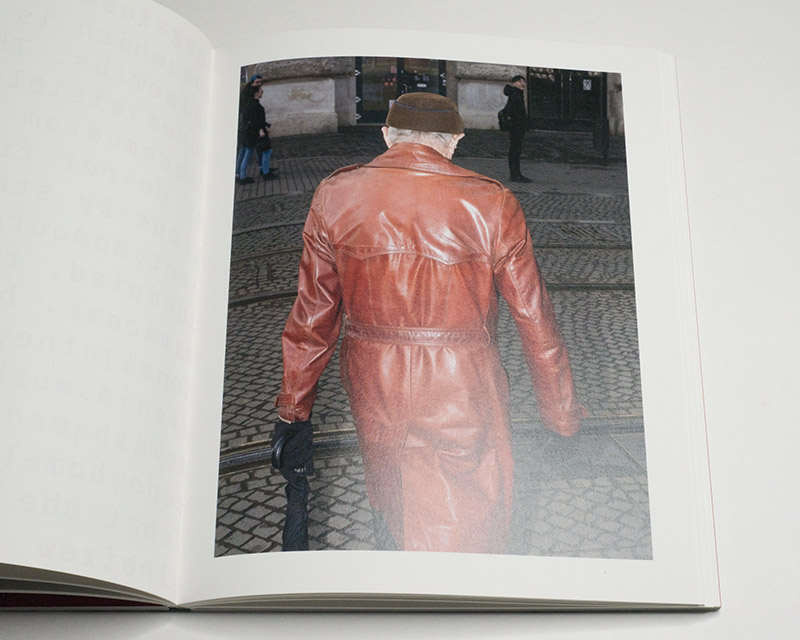

Two tailed dog is Polish photographer Michał Adamski‘s portrayal of Hungary. The book is named after the Hungarian Two-Tailed Dog Party, a satirical party that has achieved some actual electoral success. I’m liking what I’m reading on Wikipedia: “The party participated in the 2019 European Parliament election. Despite receiving 2.62% of the votes, it did not win a seat. Its campaign promises included building an overpass above the country for refugees, opening six Nemzeti Dohánybolt stores outside Hungary, introducing mandatory siesta and banning the Eurovision Song Contest.”

In a traditional political sense, such a party might appear being cynical. However, building an overpass above Hungary for refugees is only an absurd solution if you accept the problem as real. The moment you start asking the question why refugees shouldn’t be left into the country, such an overpass is not all that much more absurd than Orbán’s solution, the fence. In a nutshell, such parties subvert the widely shared assumption that elections should focus on determining which technocrat can provide the best solution for some technocratic problem (while autocrats and neo-fascists run circles around them).

In the book, a collection of scenes encountered in Hungary over the course of three years, quotes from either the Two-Tailed Dog Party or Viktor Orbán are presented. Outside of their context, they’re impossible to tell apart: both offer slogans that are grandiose and vague at the same time (along the lines of “Make America Great Again”) and pin the blame for any problem or crisis on outsiders (much like all autocrats, Orbán is both extremely nationalistic and more or less openly racist).

There is a clear disconnect between what is depicted in the photographs and the quotes — and it is this disconnect the drives the overall message home: some things are too complex to be understood with simplistic slogans. We better re-acquaint ourselves with that idea — instead of relying on “deeply divided” narratives that only serve as cash cows for today’s intellectually impoverished media landscape.

I can’t help but think that even as the Iron Curtain has come down, there still exists a clear divide between photographers from what used to be west of said curtain and photographers east of it. For a large number of reasons, that divide should not exist. But I bet a lot of people in the West would have a much easier time naming a British, German, or French photographer than a Polish, Czech, or Hungarian one.

In light of the fantastic work coming out of Eastern Europe and in light of how the same stories take on very slightly different meanings when told by someone from there, we ought to be doing more work to bridge the divide.

Holzbachtal, nothing, nothing; photographs and texts by Sibylle Fendt; 168 pages; Kehrer; 2020

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.4

Two tailed dog; photographs by Michał Adamski; appropriated text; 96 pages; Pix.House; 2019

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 3.0 – Overall 3.1

Ratings explained here.