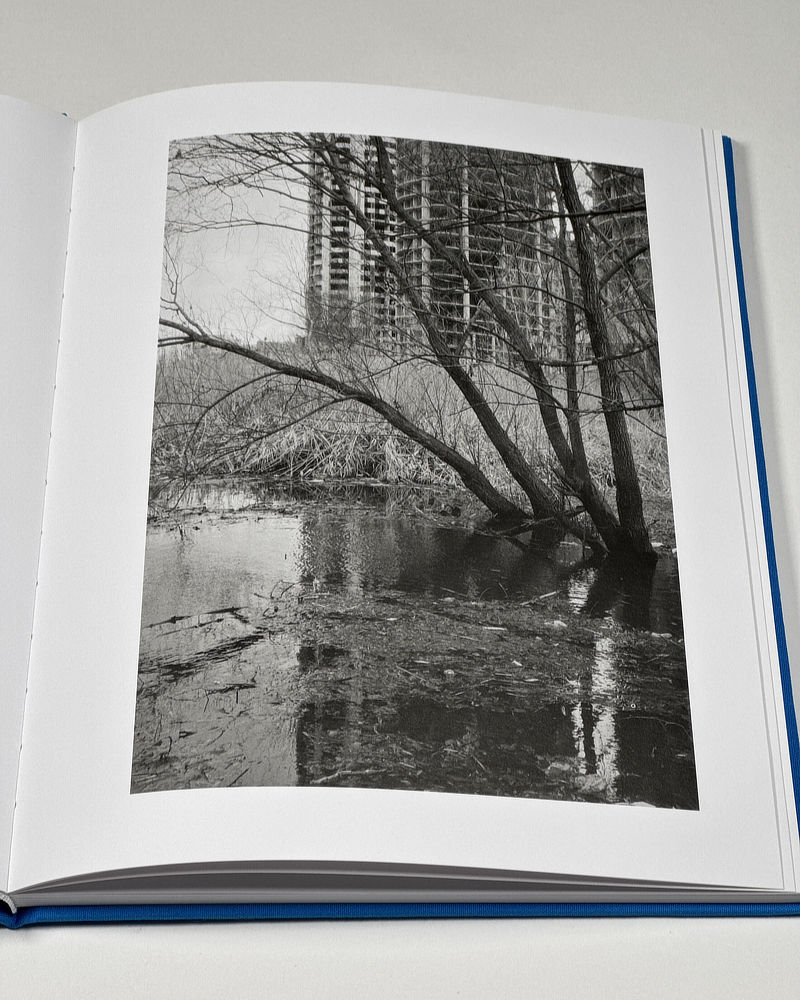

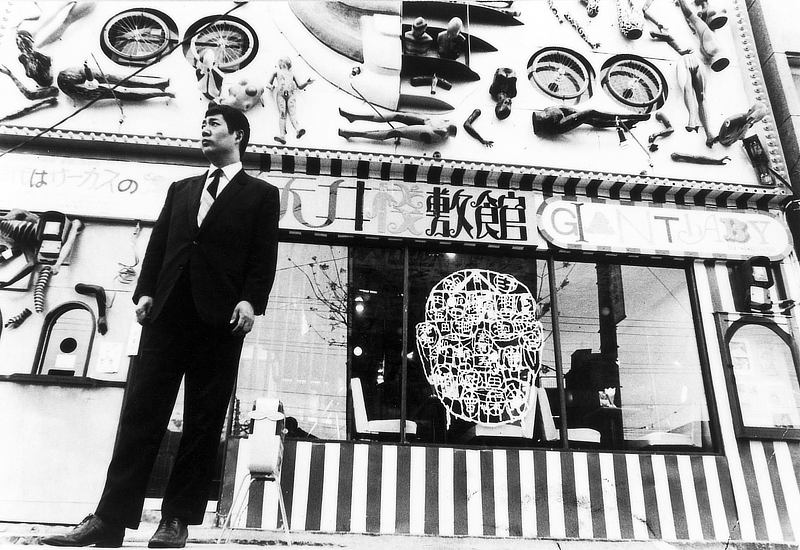

Different generations of artists often define themselves through opposition: as a new generation emerges, it attempts to set itself apart from what came before by rejecting the tradition it is forced to grow into. Whether or not the presence of larger historical and societal circumstances is needed to create revolutionary new forms of artistic expression I would not know. But in Japan in the 1960s (and to a slightly lesser extent in Germany at the same time), it was the combination of those three factors that produced some of the country’s most inventive contemporary art.

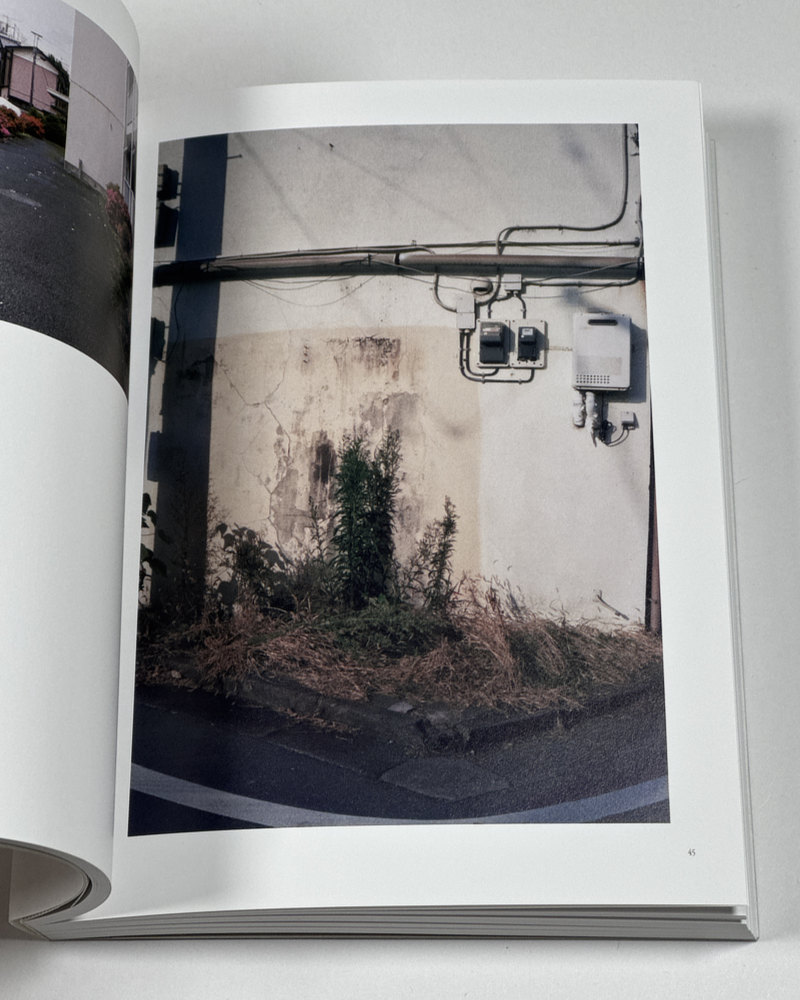

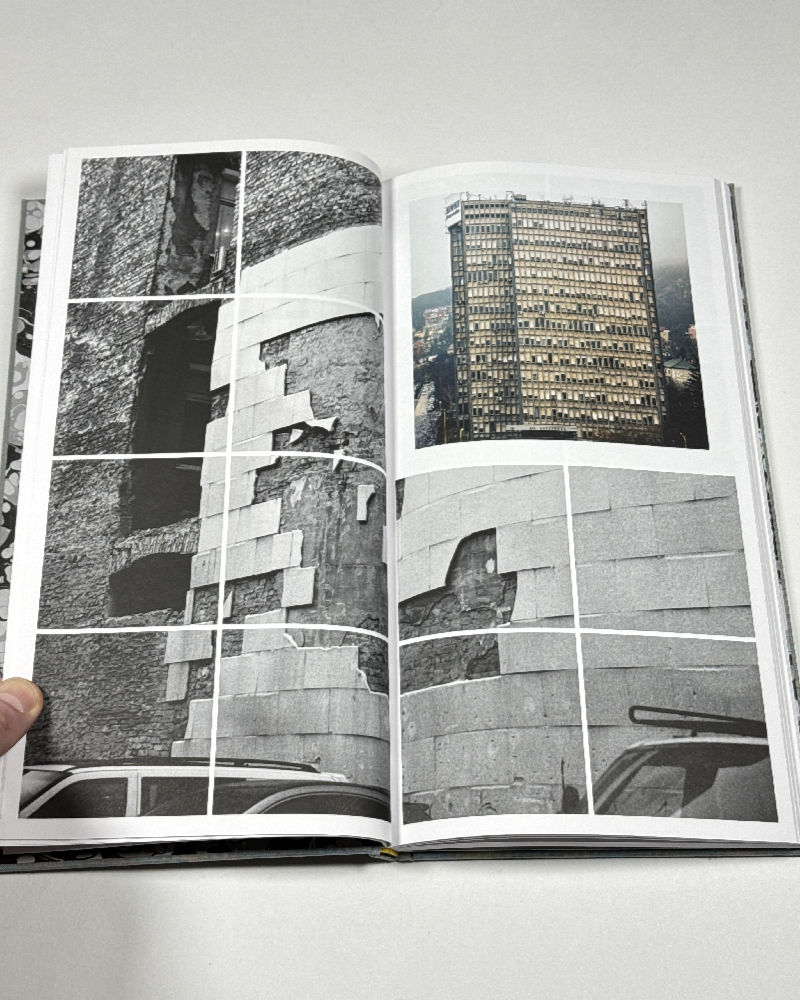

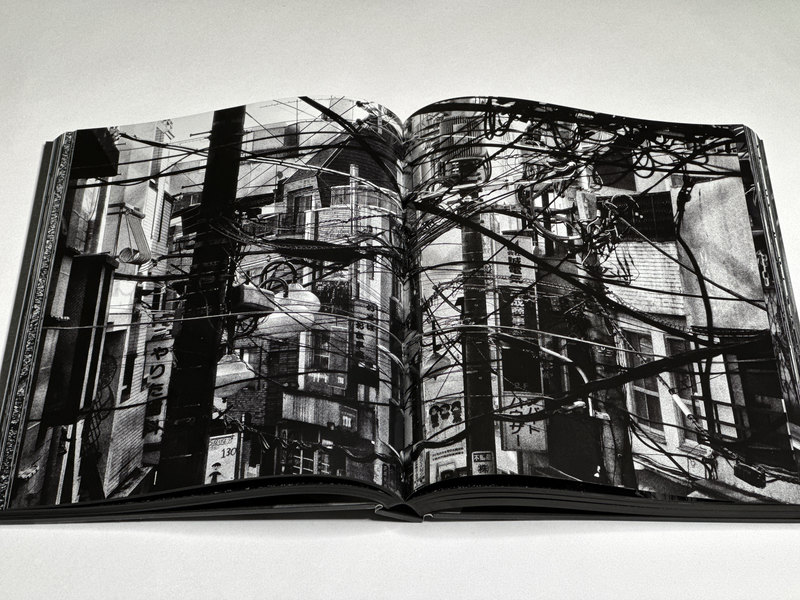

By the 1960s, Japan’s political establishment had created the model that it would continue to ride up until today: offer citizens unprecedented material advances in such a fashion that they will not ask for a change in the political structure. The first major expression of the model was produced for the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, which saw vast parts of Tokyo re-constructed and connected to some of the rest of the country through the now famous shinkansen (bullet train).

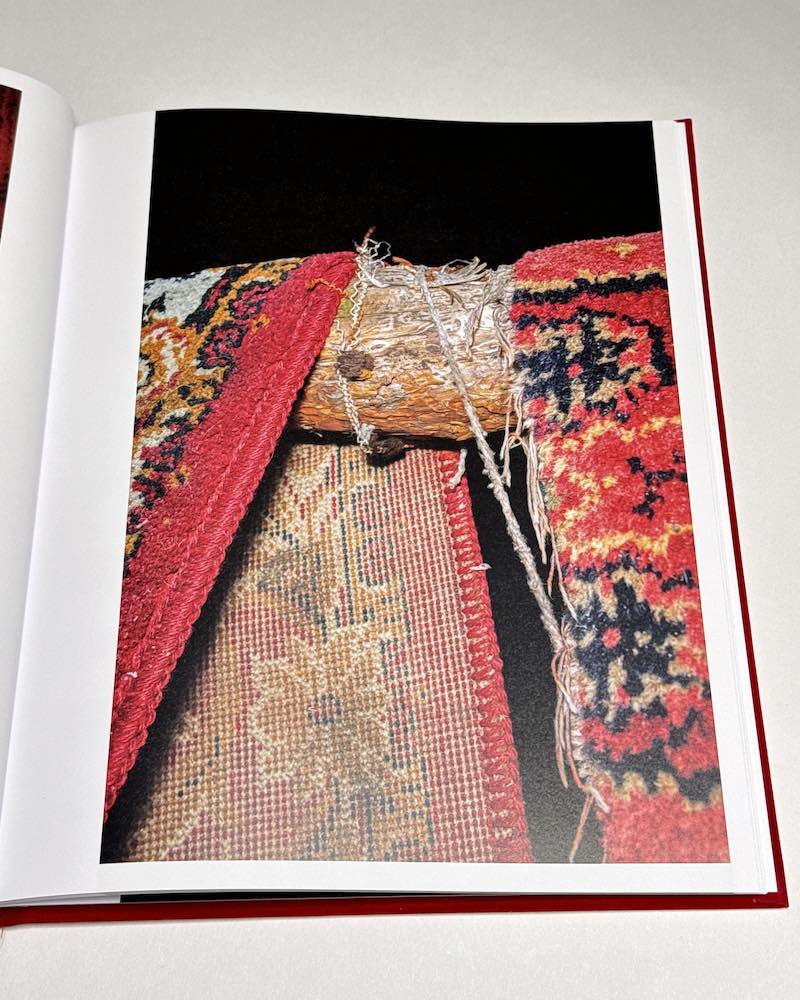

Just like in Germany, the economy exploded, making many previous luxury items widely available. It was the beginning of the consumerism that, for better or worse, has shaped Japan ever since. Meanwhile, about a century after the country had opened itself back up to the world the struggle between modernity (often in the form of imports from abroad) and tradition continued unabated.

The continued presence of American military forces in the country predictably created unrest: there were large student protests against the re-signing of what as known as ANPO, the United States–Japan Security Treaty that in part outsourced Japan’s defense to the US but that also provided the US with a convenient military base from which to wage its war in Vietnam (earlier in Korea).

For the artists who had experienced World War 2 either as adolescents or children, growing up into this particular world created a unique opportunity. But maybe this phrasing assumes that as a participant of an event you have more agency than you actually do. After all, none of the artists portrayed in Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers, a new documentary, appeared to have considered their position with a bird’s eye view.

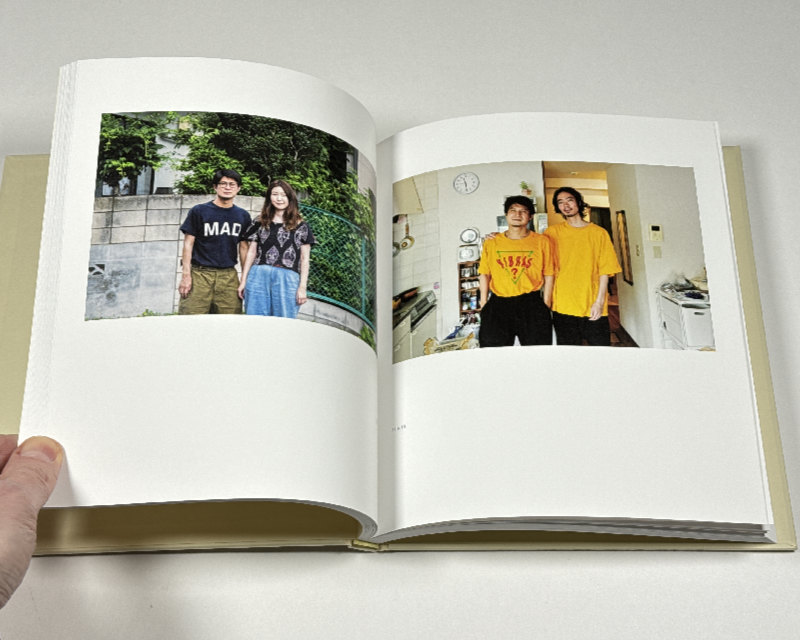

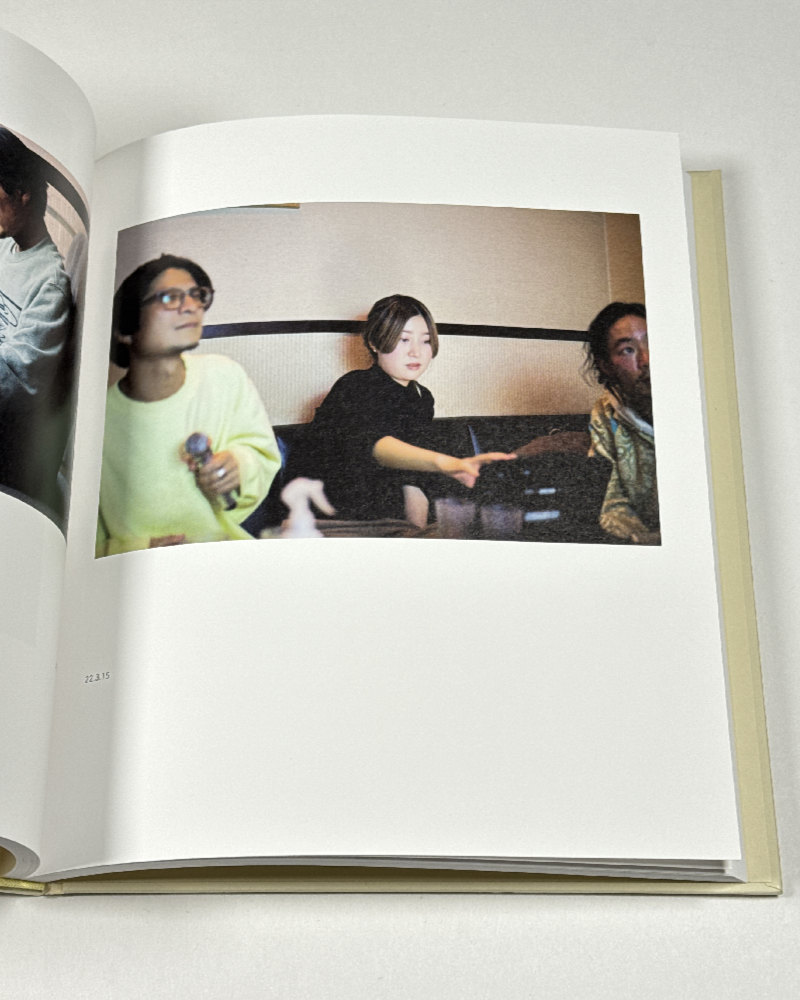

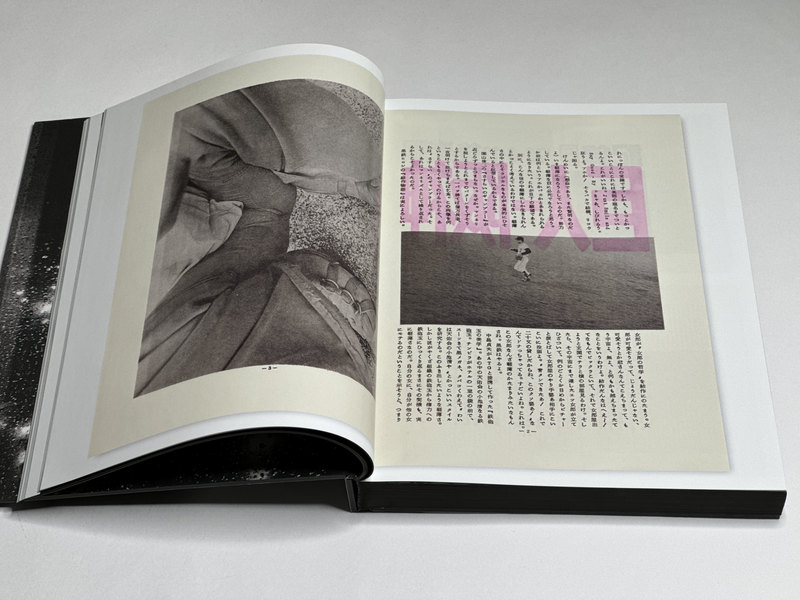

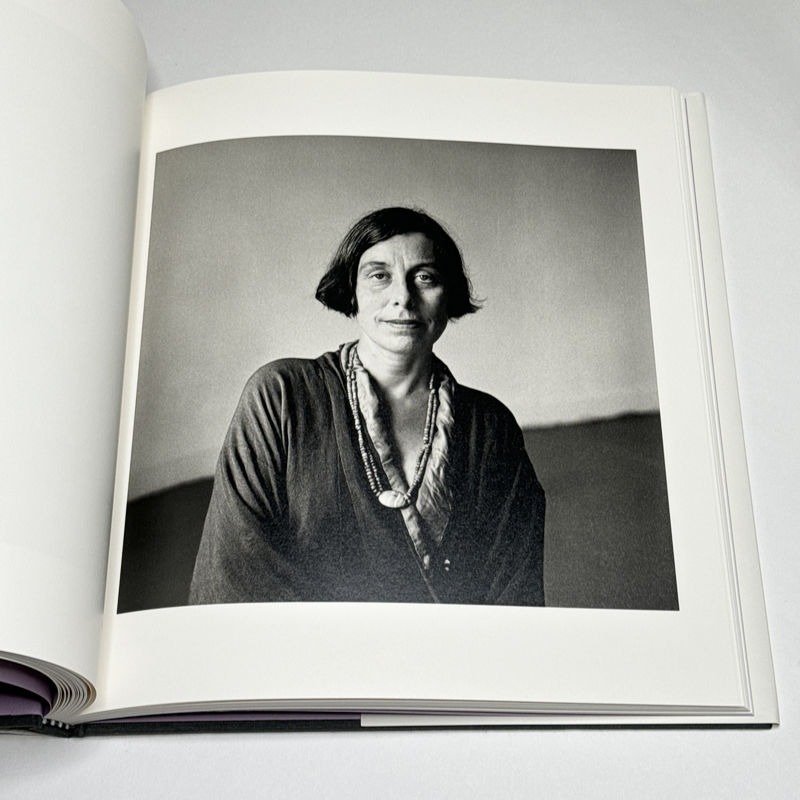

And how could they? Theirs were unique circumstances, and they made the best of them. We know this because Moriyama Daidō, Hosoe Eikoh, Ishiuchi Miyako, Tanaami Keiichi, Yokoo Tadanori, Terayama Shūji, Kawada Kikuji, and others speak about their experiences and ideas in the documentary. Some of the footage is archival (for example Terayama Shūji already died in 1983), while the bulk of it is new.

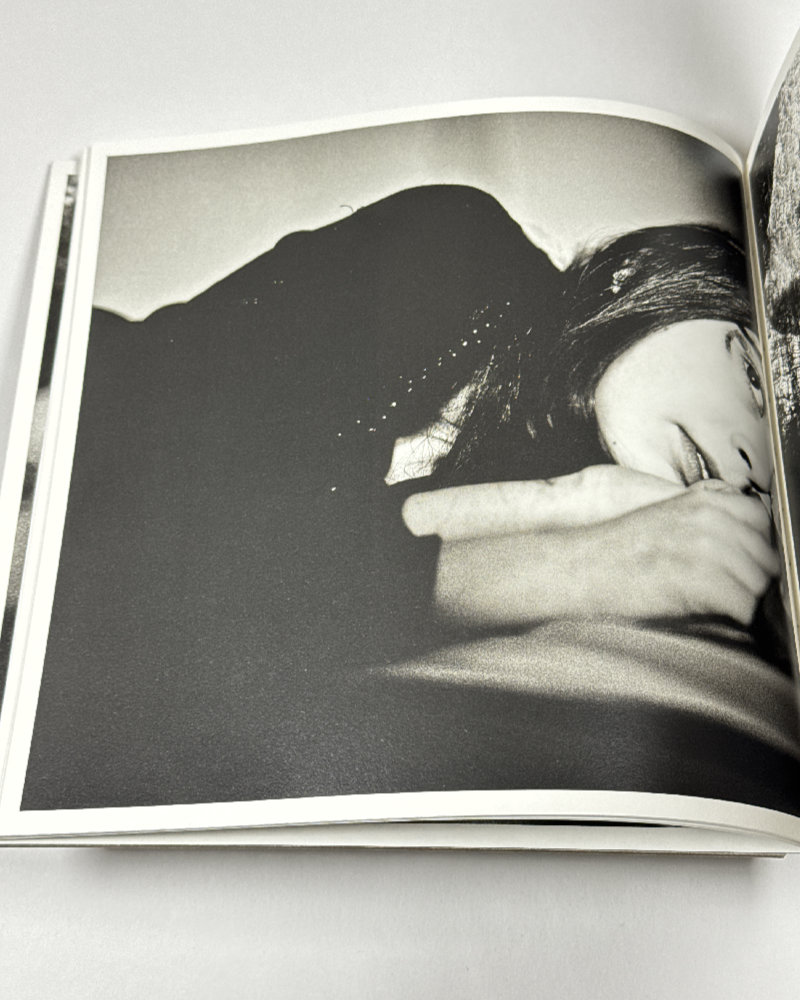

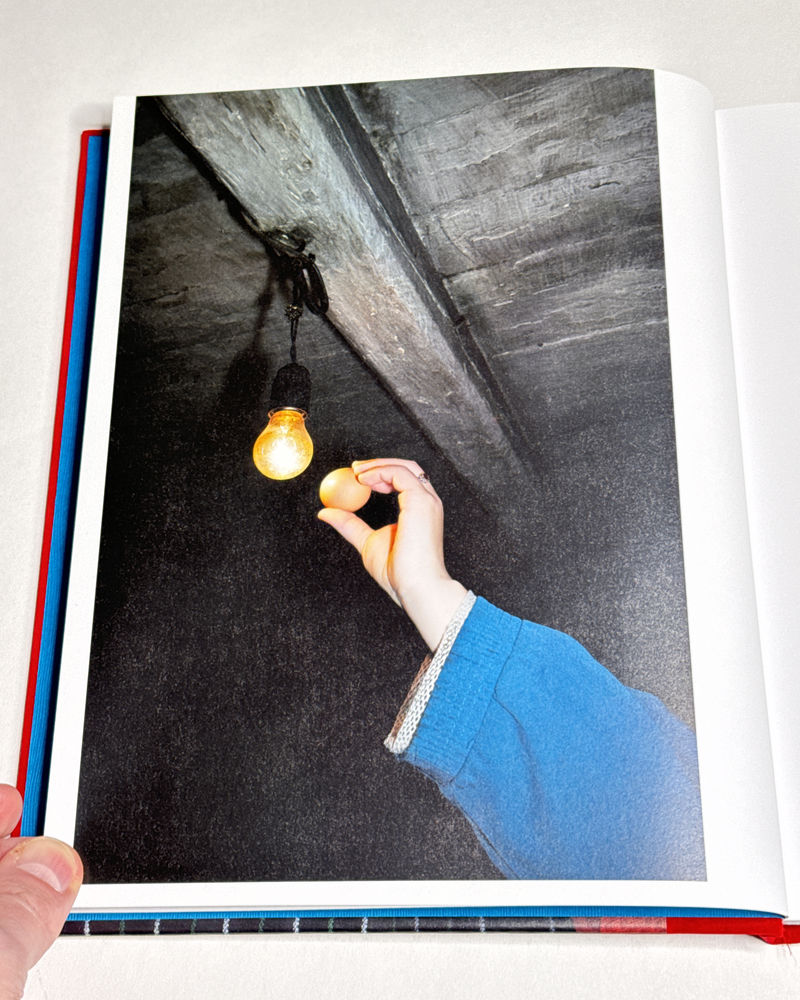

Perhaps not surprisingly, many of the artists either knew each other, or at least they knew of each other. Occasionally, they would collaborate to create pieces of art together, such as when, say, Hosoe Eikoh photographed Mishima Yukio, the extremely image conscious writer, actor, poet, and far-right nationalist, to produce what became known as Barakei (Ordeals by Roses).

The importance of being able to see these Japanese artists speak about their work and motivations cannot be overstated, given the extent with which it enriches appreciation for what they achieved. Sadly, as is usually the case the photographers provide the least interesting examples, possibly because so many of them are stuck in only their own medium (Kawada Kikuji is the notable exception).

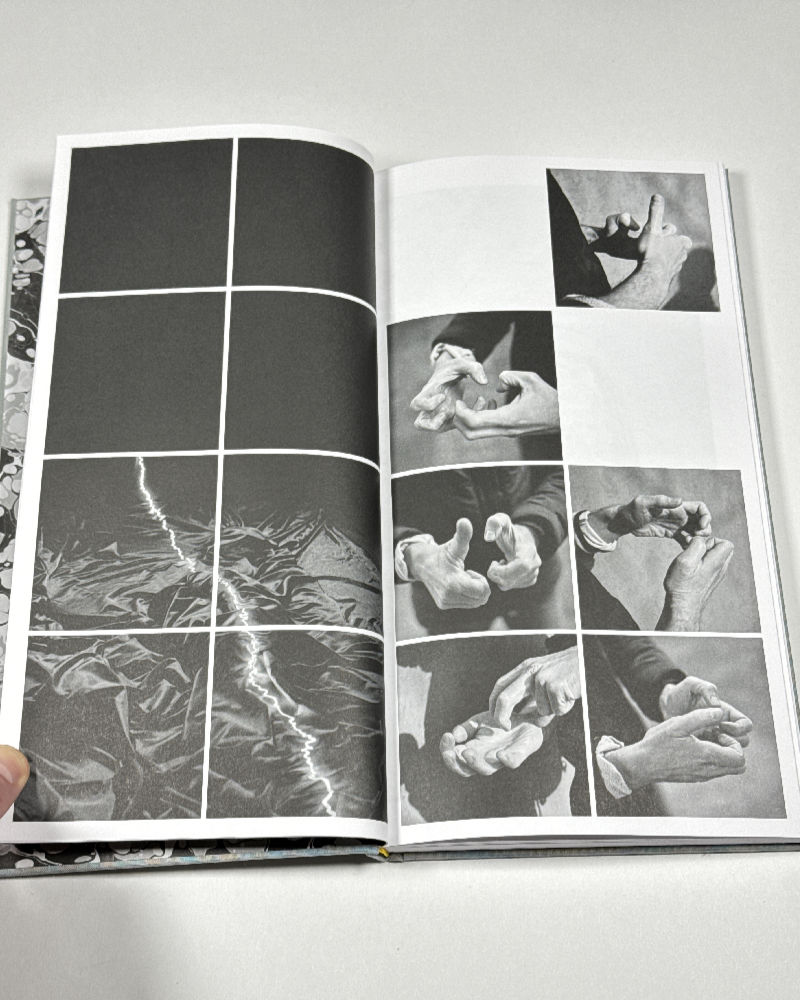

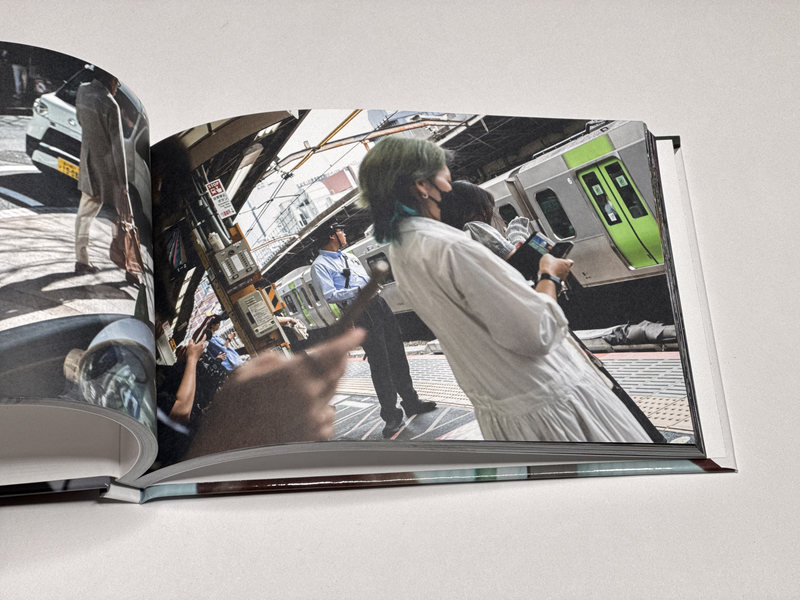

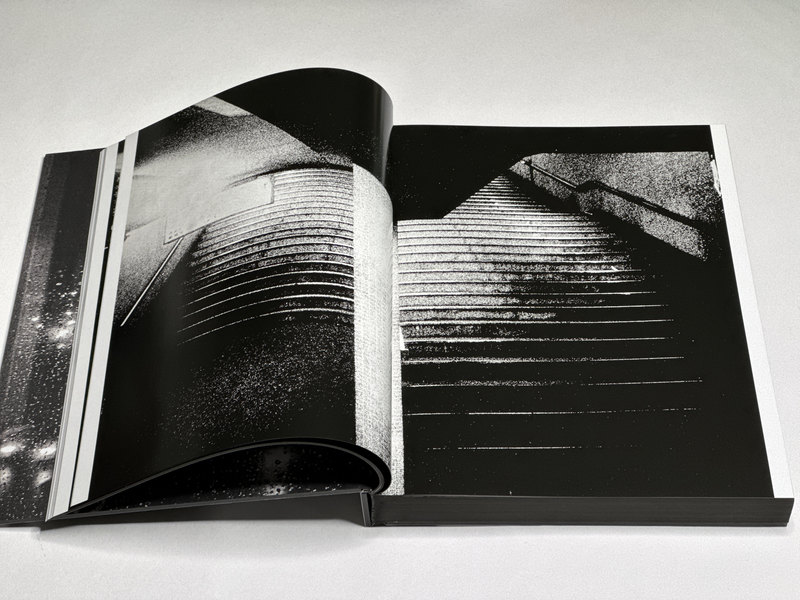

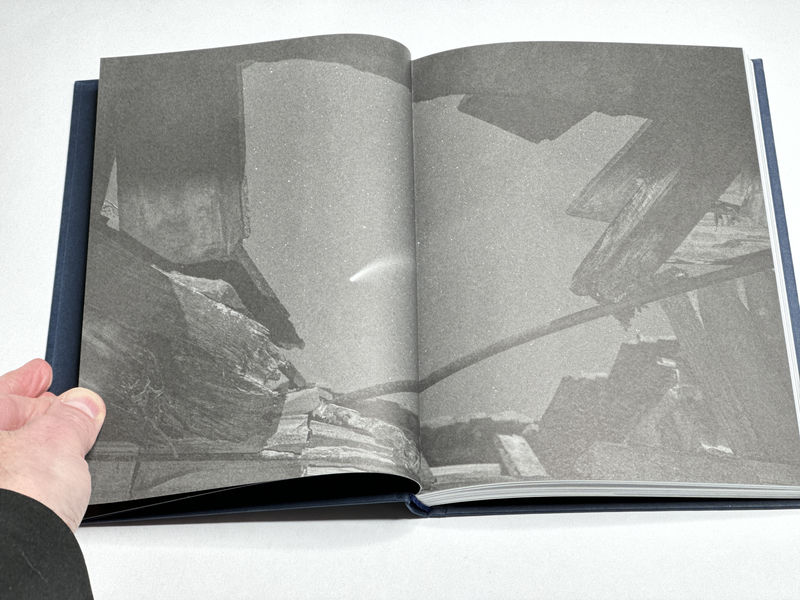

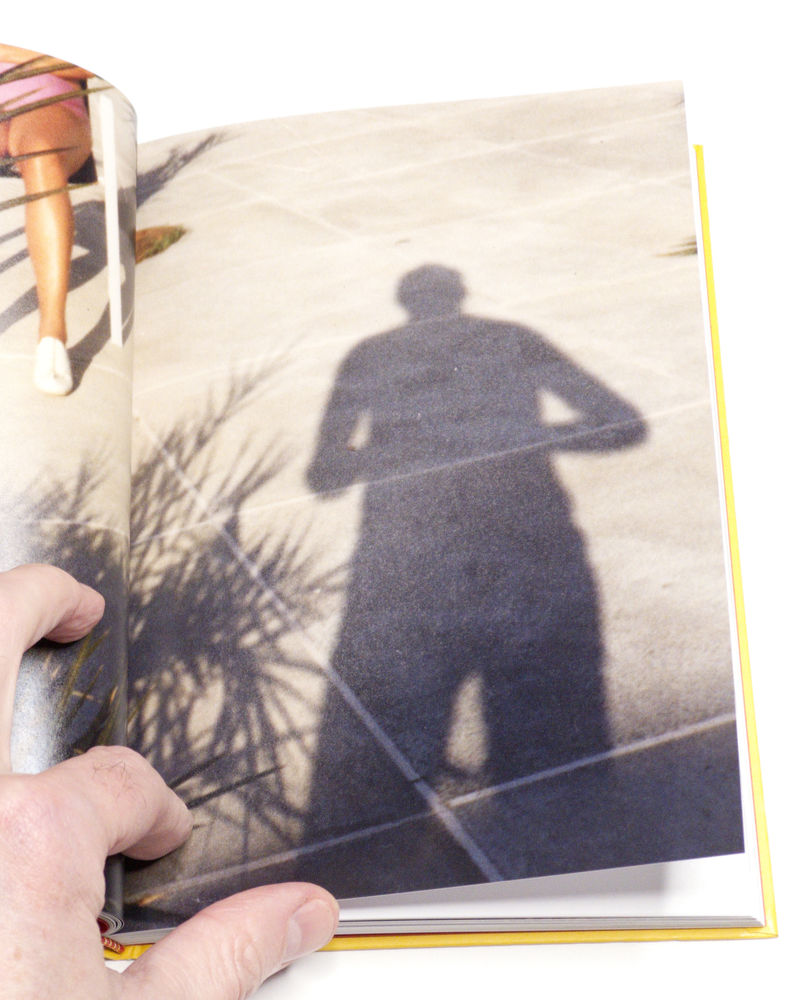

For me, the most visceral experiences were seeing contemporary footage of art pieces that until now I had only heard about, such as when, for example, Natsuyuki Nakanishi boarded Tokyo’s Yamanote Line, dressed in a suit and his face painted white, to then hang an object he had made from the subway’s hand guards, examining it with a flashlight (as part of what became known as Hi-Red Center). It was performance art at its finest, and the footage is a real sight to behold.

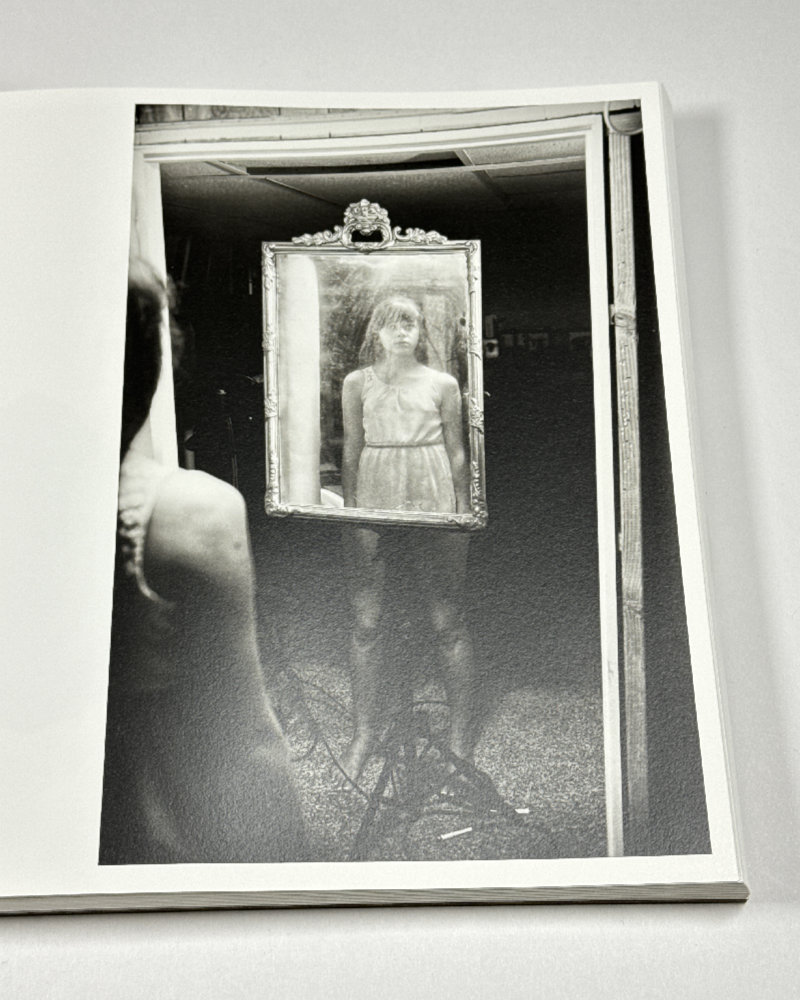

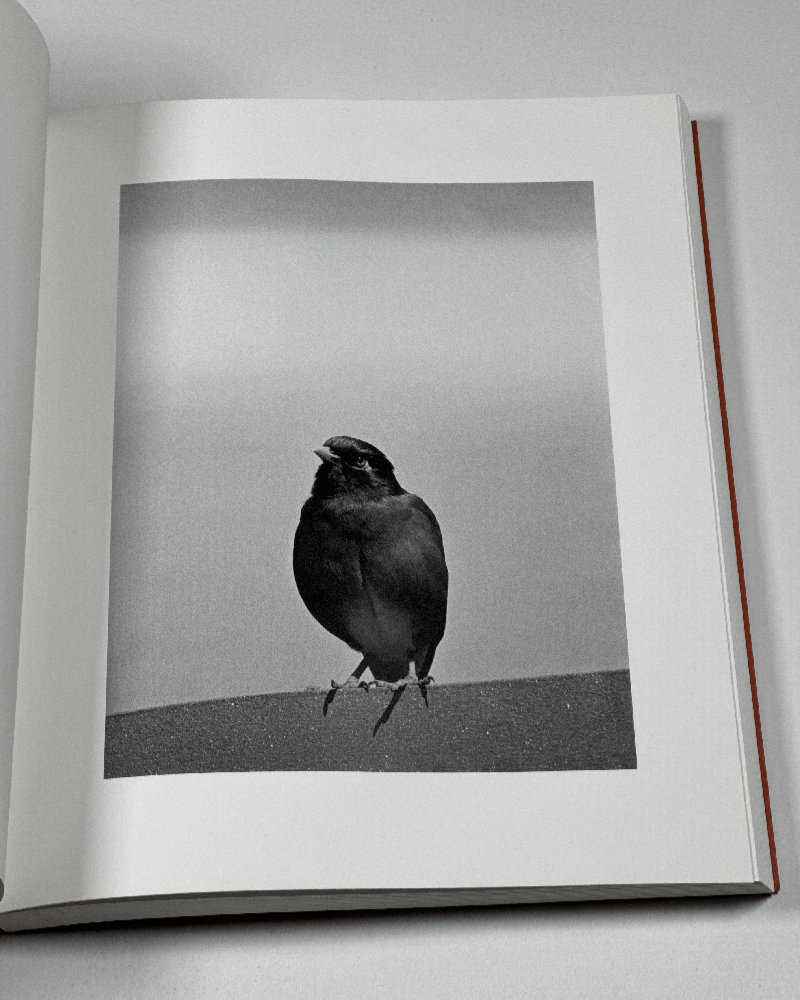

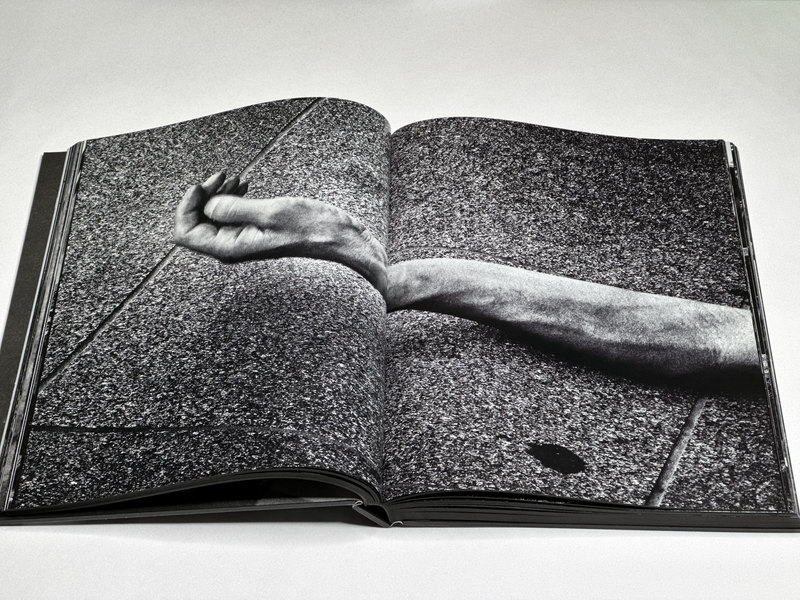

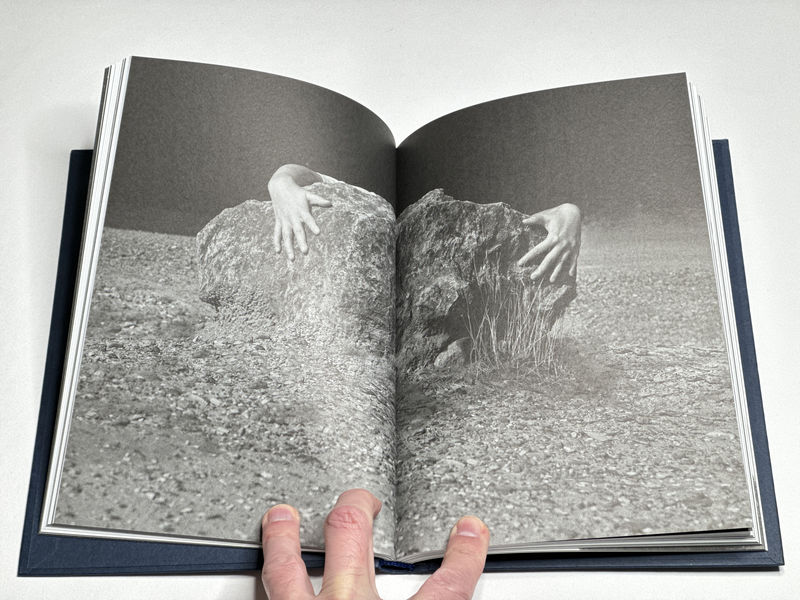

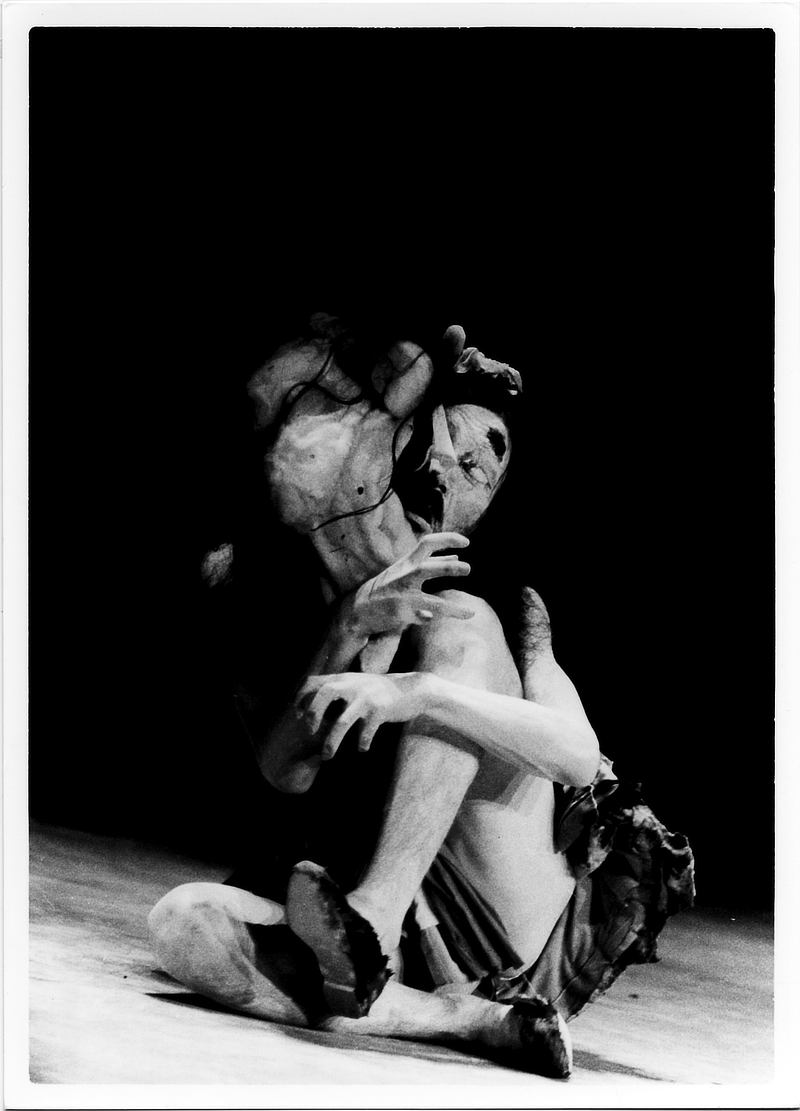

Seeing Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo perform Butoh dances (in incredibly grainy footage) also was a revelation. There are, of course, photographs (Hijikata collaborated with Hosoe to produce Kamaitachi in the region of Japan they were both from). But it became clear to me how little they can convey of what an audience might have actually experienced in person, in part because through its own nature photography freezes out the essence of this type of dance.

Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers adds context to what is on view through interviews with an assortment of Western curators. I suppose without that added context, an audience unfamiliar with what is on view might be lost. But there were some amusing moments, such as when a clearly very privileged Guggenheim curator spoke of the preciousness of some of the art that had been lost, and a Japanese artist would say right after how as a starting point for his art he had rejected that very idea.

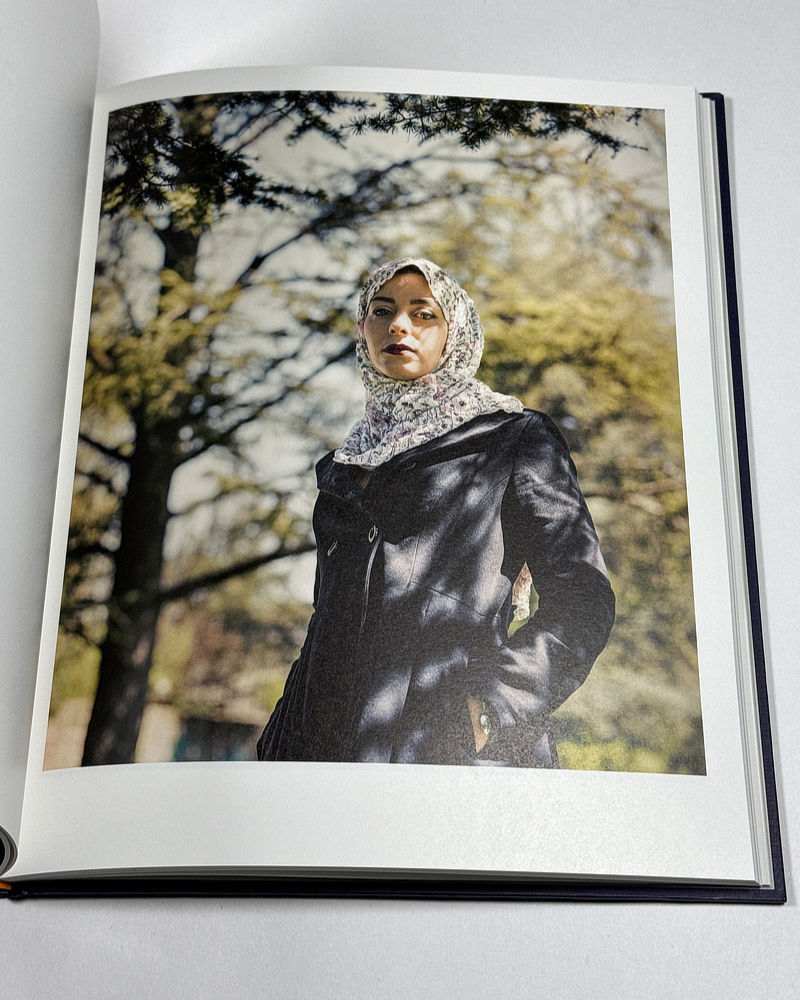

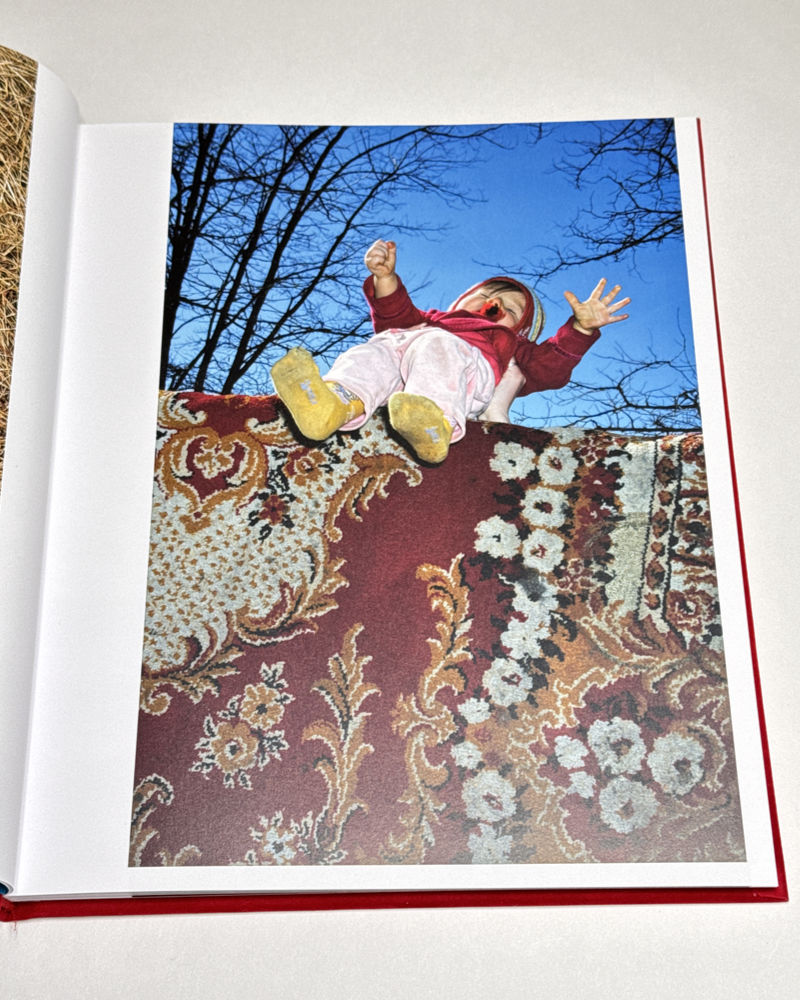

Speaking about joining the student protests, Ishiuchi Miyako says “we were freer then.”If there’s anything a viewer takes away from the documentary it is that freedom — and the willingness to make good use of it.

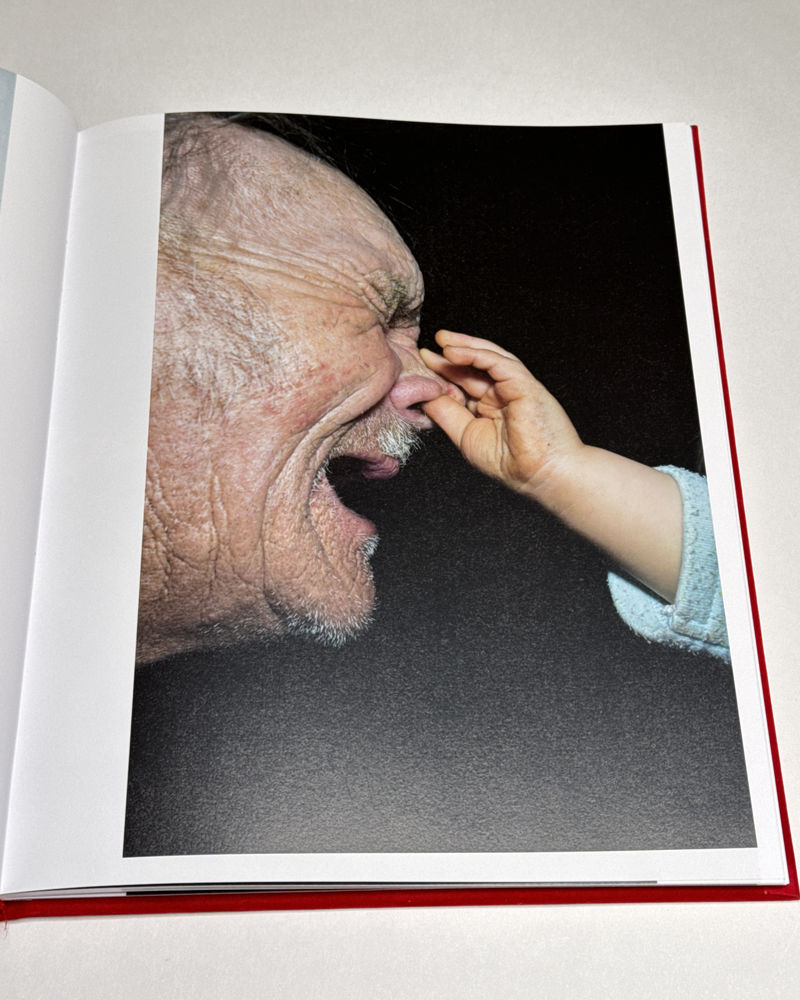

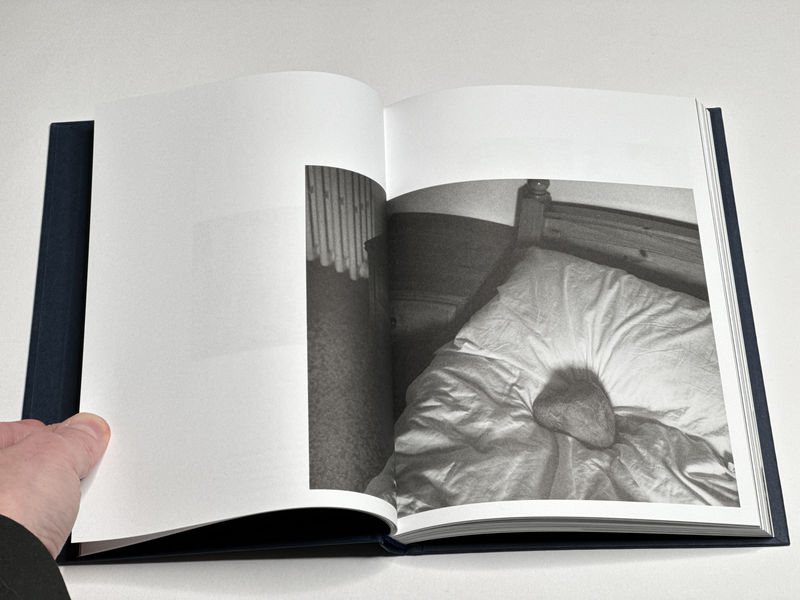

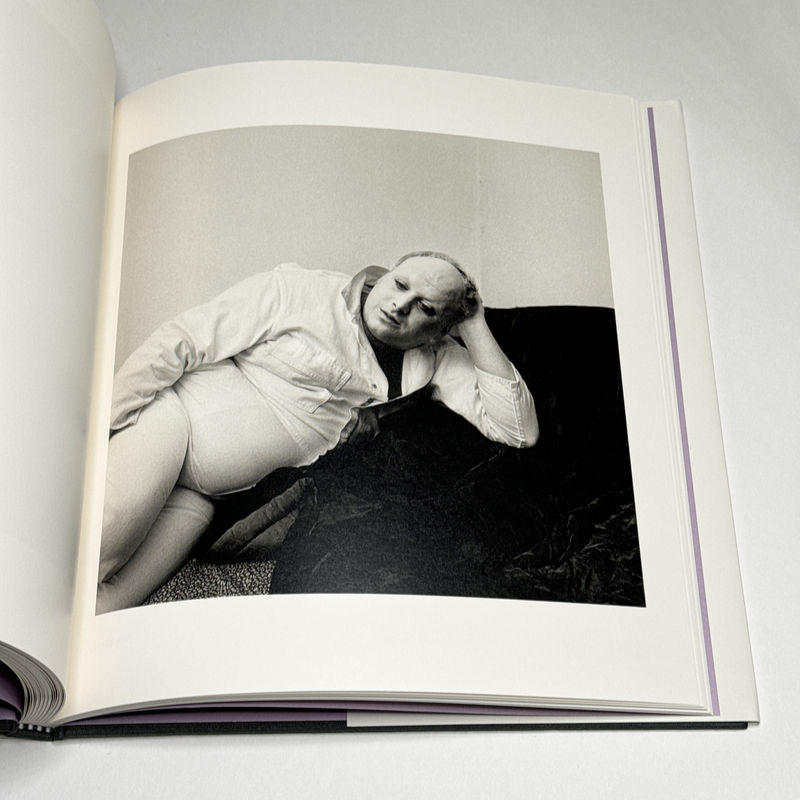

For what it’s worth, I would have preferred a dedicated section on Ishiuchi instead of on Araki Nobuyoshi, the pervy old man of Japanese photography. At this stage, Nobuyoshi Araki is the Nigel Tufnel of Japanese photography, forever dialing up the misogyny to an 11 — except, of course, that Tufnel is a fictional, comedic character.

But maybe seeing Araki serves as a good reminder that art and photography are made by human beings, and human beings reflect their own and their society’s flaws. Mishima Yukio produced incredible art, pushing the boundaries in any number of ways — only to end his life via ritualistic suicide after an attempt to stage a putsch against Japan’s government failed (the whole event has always stuck me as so outlandish and absurd that I could never shake the thought that Mishima knew that it would not succeed).

If anything, Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers not only shows that the artists it showcases produced some of the most cutting-edge contemporary art of the 20th Century; it also exposes the wide range of personalities behind that art — and the sheer wit that drove so many to reinvent themselves and part of their country.

Highly recommended.

Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers; directed by Amélie Ravalec; 1 hour 40 minutes; Circle Time Studio; 2025

Released in theaters from April 2025, with screenings planned throughout the year internationally; please refer to this page for screenings.

]]>