One of my pet peeves is being asked to comment on an art project that purports to involve a degree of science or attempts to mimic science. As if I, a former scientist, could shed more light or (this is often implied) lend more credibility to such art projects. I know this might be difficult to understand, but I’m not very eager at all to get shoehorned into being “a former scientist” forever. I don’t see those years as the most important aspect of my professional life over the past two decades.

Furthermore, I think that artists take the sciences too seriously. By this I mean that artists are too interested in accepting everything the sciences do, and their art then somehow has to play with that. It’s fine if as an artist you want to be the equivalent of a court jester for the sciences. And I do understand that there are actual repercussions of the far right and its conservative enablers undermining scientific research. We’re not going to be able to address climate change if we live in denial, and we also won’t be able to contain the Covid pandemic if we allow misinformation about vaccines to spread as easily as it has so far.

However, as someone who has worked as a scientist and as an artist, I think that artists need to reconsider their engagement with the sciences. They either need to go a lot deeper and educate themselves about what scientists actually do (regardless of what field they want to dive in), or they need to embrace the fact that they are artists and thus are not bound by the same conventions that scientists have to follow.

My guess is that the latter is seen as running the risk of embracing exactly the kind of science denial as, say, deniers of climate change. But that strikes me as a very narrow and curiously diffident approach to what art can do. Unlike climate-change denial (which is rigid and closed), art is open and generous when it is done well — and, most importantly, it aims at the betterment of the human condition.

If anything, the following is the most important difference between art and science. For the most part, art has been playing a benign role for human beings. Even where art was or is not benign (for example, if you wanted to treat Leni Riefenstahl’s movies as art instead of the blunt propaganda they are), it tends to find itself only in a supporting role. In contrast, there is a lot of scientific research that has very directly resulted in ghastly consequences. To put in bluntly, the actions of the people who painted the markings onto the Enola Gay were magnitudes less consequential than the actions of the scientists who produced the bomb that killed tens of thousands of people.

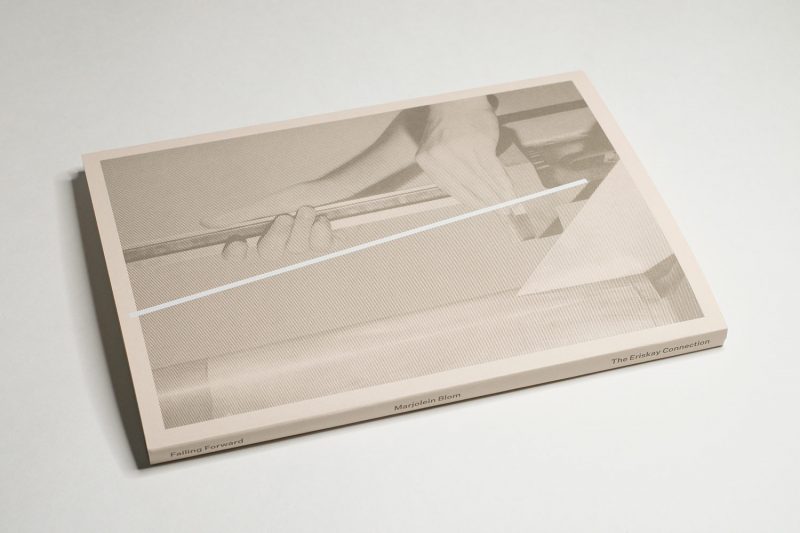

There has been a steady flow of artistic engagements with the sciences over the past decade. Marjolein Blom‘s Failing Forward is but the latest example I have come across. The book combines the artist’s own photographs with images from the NASA Archive. The latter isn’t quite what you might imagine it is. It’s not a repository of space photographs. Instead, it collects photographs taken in any of the laboratories and workshops, resulting in the kind of imagery that would fit into Larry Sultan & Mike Mandel’s Evidence.

In fact, in an article about Evidence, Sandra Phillips writes: “Mandel and Sultan found the local offices of NASA and the Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, in nearby Sunnyvale, and though they were interested in the expected beautiful pictures of space coming in across the wires, they were fascinated by the chaotic, marvelous, mournful, and funny pictures of people engulfed by a new technology no one could understand but experts.” “Evidence,” she concludes, “therefore, is a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate work of art, one that engages the loss of belief provoked by that era and an examination of the resulting ambivalent relationship of people to the new machines.”

Phillips’ perceptive description of Evidence hints at something at play in Failing Forward as well: the starting point for the artist’s endeavour is the set of contemporary conditions into which the sciences are embedded. There is a similar “loss of belief” present, albeit one caused by conspiracy theories and far-right cranks, and instead of the “examination of the resulting ambivalent relationship of people to the new machines” (which sounds very 1970s, doesn’t it?), here it is the idea of truth itself.

“The truth is,” the press text around the book claims, “that science actually is a temporary and uncertain activity, with ambiguity, curiosity and unpredictability as fundamental elements of its process.” I don’t want to dive into how and why this text hints at a profoundly misguided understanding of the scientific method. What it does, though, is to project its author’s own ideas onto the sciences — much like Sultan & Mandel did.

Seen that way, Failing Forward doesn’t really center on the sciences and what they do. Instead, it uses an artist’s idea and toys with it — against the contemporary backdrop of fake news, QAnon, climate-change denial, etc. It asks how we make sense of the world through how we process and organize it, which in this artist’s case means: how we photograph it. In a nutshell, it is one of those books that presents a pretend world through a combination of found and made photographs.

One of the problems these kinds of books inevitably struggle with is that photographs as selected by artists from institutional archives are too interesting on their own. In part the following statement is a little bit unfair, but it’s true nevertheless: Sultan & Mandel solved that problem in part by being pioneers. The first time someone does something it for sure is a lot more amazing then when you’ve seen a lot of examples. But of course, given that they placed their focus more narrowly on the archives, the visual strangeness of the photographs — which, it is important to remember, are only strange because they were taken out of one context and placed into a very different one — added up to more.

Here, I don’t quite think that Blom’s own photographs can compete with the NASA ones. Mind you, they’re good photographs. But they were made for the context they operate in, whereas the NASA ones were not. And you can feel that difference. This is why I always caution photographers to be very, very careful with archival material (regardless of where it’s coming from): it draws a lot of attention onto itself. As an artist, you will have to steer that against with all your might.

All of that leaves me with… well, what? I’ve been trying to come to a conclusion, but I might as well admit that I am unable to. The press text describes the book as “shifting between the enigmatic and the specific, between the clear and the ambiguous”, and I think that might just ultimately be the problem. If you shift “between the clear and the ambiguous”, ultimately you’ll just be vague (but not in a good way).

I like the imagery in Failing Forward, and I like the way the book is put together. But as a viewer, I don’t know what I’m supposed to take away from it.

Failing Forward; photography by Marjolein Blom with images from the NASA Archive; essays by Merel Bem and Vincent Icke; 120 pages; The Eriskay Connection; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!