Even as the following exercise is limiting in a number of ways, it would be instructive to describe the state of German photography since the end of World War 2 as being caught between two married couples, with all partners being photographers. You would have the cerebral and cold photography produced by Bernd and Hilla Becher at one end of the spectrum. At the other end, you would find the photography made by Ute and Werner Mahler — filled with emotion and precision (a tricky mix: try achieving it!).

You could fill all kinds of interesting details into such an investigation, many of them contested and loaded with political explosiveness, West Germans and East Germans, say, or city (and by extension industrial) versus rural life. And there might be much to be gained from looking at photography that was made in the kind of negotiations that is entailed between two married partners.

As I noted, this particular exercise is limiting. Why would the partners have to be following traditional family ideas? Where are the 25% of today’s Germans who are the ones to exist with an asterisk next to their Germanness (the fact that they have “a migratory background”, as the remaining 75% define them, while enjoying the privilege of simply being German [imagine furious winking by those at the now considerable far-right end of the political spectrum])?

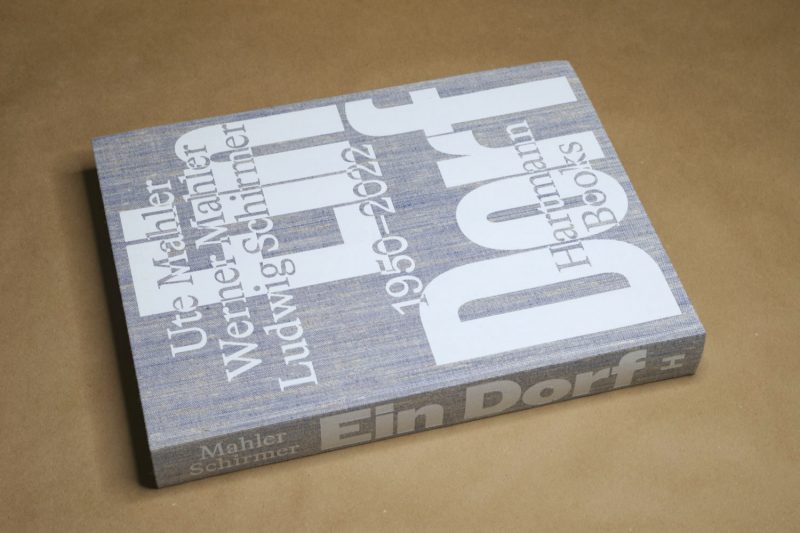

In the following, I do not intend to expand on the idea of the exercise. I will ignore the Bechers whose work, after all, has been talked about quite enough. Instead, I want to make the case that Ute and Werner Mahler have just released a landmark publication of photography that should be looked at and studied widely. It’s a book with the rather modest title Ein Dorf (A Village).

It would be unfair and improper to omit the third photographer involved, Ludwig Schirmer, especially since he was the one who got it all started. By trade a miller, Schirmer lived in a small village named Berka. If you imagine the map of today’s Germany, the village would be located to the northeast of its geographical center. This is where Schirmer picked up photography, to document village life for around a decade (before leaving for East Berlin to become a well known photographer there).

Schirmer had a daughter named Ute who caught the photography bug as well. Ute proceeded to marry a guy named Werner Mahler, himself a photographer. There you have it, Ein Dorf is also a family affair.

If there is one defining property of a village, regardless of where it is located in the world, it is that people with aspirations tend to leave. This is not to say that village life is unable to fulfill aspirations. But there are aspirations and aspirations, and some can only be taken care of in larger cities. Many people go back regularly to where they are from, because for them it is a magical place (a sentiment that entirely escapes this writer).

The Germans have a word for that — Heimat — and in true German fashion, they believe that it’s a term that has no equivalent anywhere else. That’s obviously nonsense, but it’s best not to argue with them over what they hold dear (even as the connection of Heimat and far-right ideology in Germany certainly is more than merely worrisome).

Ute and Werner went back to Berka at different times to take photographs. Werner went in 1977/78 and 1988, Ute went in 2021/22. You thus have three incredible photographers taken pictures of a small German village over a time span of a little over seven decades.

And that’s Germany, where the village had just emerged from World War 2 (in at least one of Schirmer’s photographs, a man missing a leg can be seen: a veteran), underwent decades of Communist rule, only to then undergo yet another transformation as the country was united into today’s hypercapitalist Germany.

In other words, in this small village, you can trace considerable aspects of recent German history through photographs. You can see the village and its people change. In itself, that would be remarkable enough.

But it’s the fact that the three photographers also were (in the case of Ute and Werner still are) incredible photographers that makes this book such an important contribution to German photography. In lesser hands, the photographs would have still allowed for the study of village life. But through the hands of these three photographers, the sociological or anthropological aspects of the work co-exist with its artistic ones.

Often, when someone writes an article about portrait photography the one name that gets mentioned is August Sander’s. Undoubtedly, Sander’s work is amazing. However, various aspects of it are typically not discussed, even as they’re very much apparent in the work. In part, this might be because of the photographer’s own organization of the work.

If you ignore that part, you can see the different German countries Sander photographed in as well. The farmers on their way to the dance originate from a completely different world than the cool secretary who is smoking her cigarette while being perched on her chair. And that latter world then got destroyed by the Nazis. Sander photographed them as well; you can also see proto-Nazis in some of the pictures.

If you now add Ludwig Schirmer’s, Ute Mahler’s, and Werner Mahler’s photograph, you have a visual record of Germany since about 1900 that traces the various ideologies that — for better or worse — shaped the country (and larger parts of Europe in a mostly very destructive fashion).

As is the case with most photography books, Ein Dorf comes with a set of essays. There’s one about photography, and that’s the least interesting one. There’s a sociological one that unpeels what we might see but not notice. There’s an essay that outlines the history of the protagonists and the village. And then there’s a literary contribution, which for me is the highlight.

If you’re at all interested in photography, you would be out of your mind if you didn’t order a copy of this book. It not only is absolutely incredible, it also is a landmark publication for photography from and about Germany, the terribly flawed country that sits right in Europe’s very center.

Ein Dorf 1950 – 2022; photographs by Ute Mahler, Werner Mahler, Ludwig Schirmer; essays by Jenny Erpenbeck, Anja Maier, Steffen Mau, Gary Van Zante; 362 pages; Hartmann Books; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!