There is something incredibly unsettling about Hans Eijkelboom’s People of the Twenty-First Century. Or rather there are a few of those things. They cannot be fully comprehended without pointing out that the book clearly references August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century.

Both titles are each off by one century. Sander’s pictures informed large parts of what we consider modern and contemporary photography. But his ideas and sensibilities were firmly rooted in the Nineteenth Century, in the mostly studio photography of that era, in the – misguided – belief that people could be categorized based on rather strange categories, in the attention – crucially – that the individual was given. It is the latter that makes Sander stand out, possibly forever stand out: his photographs are portraits of a large number of people, but one can feel a concern for the person(s) in front of the camera’s lens that today is largely gone (remember, ours are the “selfie” times).

Working mostly during the first three decades of the Twentieth Century, Sander recorded what was carried over from the Nineteenth, most of it changed, discarded, destroyed before his century was half over (this includes large numbers of the photographer’s work: glass plates destroyed in one of the many Allied bombings of Cologne). Modern democracies, whether failing or not (and when failing resulting into neo-Neanderthal political systems, the most gruesome of which – Sander’s own, the German – reverted to Stone-Age style barbarism), in combination with modern capitalism and its most important consequences, modern warfare and the consumer society, made minced meat out of most of the ideas of the Nineteenth Century.

This is part of what makes looking at Sander’s photographs so interesting. They’re not only fantastic photographs. They also seem to speak about a time that was so different, even though the people in the pictures look so similar to those around us. If we had photographs from, say, the Dutch Golden Age, I don’t think we’d see the same similarities. Even many photographs from the Nineteenth Century feel very different. Those portrayed by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson don’t look like they could at any moment emerge from the pictures, to walk down the streets along us. Sander’s subjects, in contrast, feel a lot more familiar.

Especially when dealing with photographs of people (whether we want to classify as portraits or not), the issue always becomes whether we feel the portrayed are of our time or not. This might seem like a trivial and irrelevant point to make, but I think it’s quite important. Hans Eijkelboom’s essentially work centers on the (late) Twentieth Century (carried over into these first years of the Twenty First), or more accurately on the results of that period, with decades of consumerism having made their impact. We can find ourselves in those pictures, we could imagine walking around any town alongside those depicted.

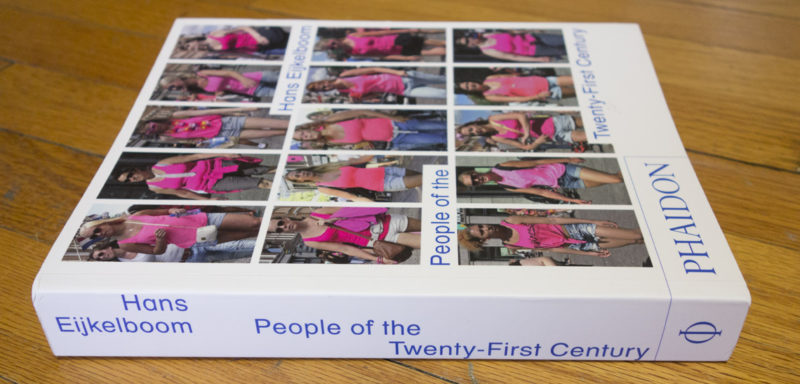

November 9th, 1992, Arnhem (NL), a lunch hour: fifteen people wearing bright red jackets. So it begins. December 5th, that same year and town, in the early afternoon: fifteen women sporting rather loud winter coats, featuring colours made popular in the 1980s (luckily all gone now). And on it goes, with jackets and trench coats, short pants, people carrying business suitcases, pushing strollers, riding their bicycles, holding hands etc. etc. etc. We finally arrive on November 10th, 2013, in Amsterdam, in the afternoon, with sixteen women wearing pink jackets.

Whatever distance we can (or simply automatically will) establish between the person(s) in a photograph and us will determine to what extent we will allow ourselves to be affected by what we see. Through the fashions of the days, Eijkelboom’s photographs feel a little distant or fairly close to us. But given there are always grids of photographs, the portrayed become specimen. We don’t really look at those sixteen women, photographed on November 10th, 2013, we look at sixteen pink jackets.

If the point is to be made that the fashion of our day, provided we stick to it, reduces us to people who are willing to give up their individuality, at least to some extent, then the presentation of these photographs underscores that very point. Which is fine. But at the same time, it also has faint echos of the idea that you can classify people based on their appearance. I suppose photography simply can’t run away from that (see the marvelous Police Pictures for some of the history).

But apparently, that’s not the point, The essay at the end of the book, written by David Carrier, focuses on the issue of individuality and how this individuality could be tied to what one decides to wear. “Judging people by their clothes,” Carrier asserts, “is not as superficial as it may seem.” And: “the closer you look at any page of this book, the more diverse you will find the people who are dressed in similar way.” I’m not sure to what extent I buy this. After all, it is one thing to look at a grid of gas tanks in a Becher typology to study the differences in their structures. But gas tanks aren’t people. We don’t look at a picture of a gas tank the way we look at a picture of a person. We could never imagine being that gas tank, but we could certainly imagine that person (at least to some extent).

And even if I want to believe that a grid of people forces me to look at people individually, which to be honest I never did until I learned from the essay that that’s what I was supposed to be doing, it’s still a grid of people, a collection of specimen. If you want me to look at people’s struggle to express their personality given the choices they face, then don’t show me that struggle in a way that points at the complete opposite, at people being conformist and sticking to the same thing.

This all leaves me a bit torn about People of the Twenty-First Century, which is engrossing in all kinds of ways, but which also at least in part seems to be doing the exact opposite of what it claims to be doing. But then that is bound to happen in a book filled with photographs of human beings – we react to those in ways that are hard to predict and certainly hard to control.

People of the Twenty-First Century; photographs by Hans Eijkelboom; essay by David Carrier; 512 pages; Phaidon; 2014

No rating since I can’t make up my mind how to adapt the rating system to this book without getting a skewed number.

Ratings explained here.