In a classroom at one of the art schools I taught at a few years ago, there was a large wooden cabinet with many relatively small drawers. If you have ever been to an art school, you’ll know that with the exception of digital labs, facilities typically betray their frequent use (I’ll leave it at that). But unlike its surroundings, the cabinet was pristine. When using the classroom, I often found myself pulling out random drawers to look inside.

I knew what was inside: physical slides the types of which had been a part of the world of analogue photography before the general move to digital media. I’m old enough to remember the use of transparencies and slides in a classroom setting. As a teacher, I never used them; but when I was in school, I remember having to give presentations that involved such materials.

Inevitably, slides were iffy. Larger parts of the presentation time were spent on re-focussing the image on the screen. In retrospect, I miss the strange charm of the materials’ physical quirks: a slide would “pop” (caused by the projector’s heat), and you’d have to refocus. You also wouldn’t have to look for an adapter to connect things — maybe the time required to refocus slides has now gone into that often large chunk of time spent on looking for the correct adapter?

As time went on, the more often I found myself in that classroom, the less interested I was in looking at the cabinet. I knew what was inside. Mind you, I enjoyed the physicality of it all, and I enjoyed (and still enjoy) looking at photographs. But frankly, I found what was on display depressing: a very US centric assortment of predominantly white male photographers. This was what generations of photography students had been exposed to.

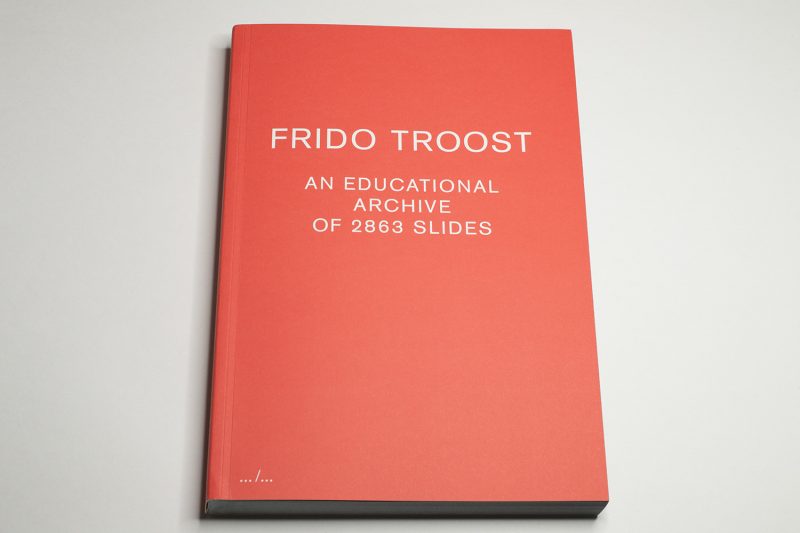

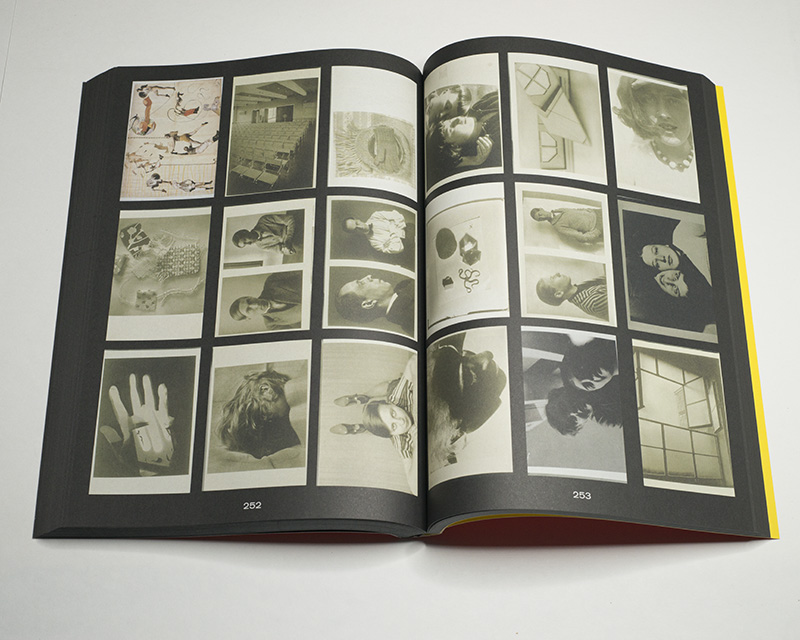

There now exists a publication that makes available a (different) full set of slides used for teaching. Entitled An Educational Archive of 2863 Slides, the book presents the images used by Dutch art historian Frido Troost who taught at Gerrit Rietveld Academie. With a few exceptions, nine slides (images) are presented per page, resulting in a 400 page book. While being fairly large, it’s printed on a relatively thin paper stock. The book handles well without being overly hefty, and the images are large enough to allow for good viewing.

In some ways, Educational Archive resembles Gerhard Richter’s Atlas (which, as far as I can tell, is now out of print). There might be an overlap in the audiences of both books: people who derive pleasure from seeing collections of images that were assembled by someone with a high degree of visual literacy. But Richter is an artist, not a historian. Maybe the Atlas to refer to would be Aby Warburg’s (full title: Mnemosyne Atlas). While I’m at it, I might as well mention Hannah Höch’s Album (sadly also out of print), compiled roughly at the same time as Warburg’s Atlas.

Educational Archive is indeed that, educational. There is an index at the end that lists the names of the artists for every slide (where such information was obtainable). The slides are organised in some fashion, but the organisation follows more loose principles. As a consequence, the viewer will end up having to make their own connections between the images, which, of course, cuts both ways: you’re not being guided, but you’re able to discover.

The scope of the imagery on display is a lot more diverse than what I encountered in the cabinet I spoke of above. As an art historian, Troost very obviously didn’t deal with only photography. But he also did not limit himself to the larger art context. The first few pages of the book show a large number of advertising: full pages from magazines showing ads for cigarettes or perfume. In fact, Troost often included more quotidian sources for his slides (as far as I can tell, the slides were made with a camera on a copy stand).

With this breadth of source imagery, Troost must have been ahead of the curve in his time. That said, in many other ways, he was not. Having seen the cigarette ads, I expected a much wider breadth of imagery in the areas dealing with photography in general. But there is ample material that runs along the lines of the male gaze or standard colonial photography.

I have no way of knowing how Troost used these materials in class. It’s possible that he discussed the male or colonial gaze critically. But I’m thinking that for such a discussion, one would need to complement the material with other images that either subvert such gazes or offer a very different way of showing the subject matter in question. Such material seems largely absent here.

This is not to say that there is no value in Educational Archive, quite on the contrary. Let’s face it, anyone dealing with aspects of visual education and/or literacy will inevitably fall short in the eyes of her or his later peers: visual literacy evolves through an increasing awareness of problems and restrictions and through changed perceptions of either what images show, what they show given a specific context, what they show based on who made them, etc. As easy as it might be to feel smug about the shortcomings of someone who came before you, always remember there will be people coming after you.

Thus, Educational Archive is a pointer of a time and place. Part of that pointing is done not only by what is stressed but especially by what is excluded. Visual literacy always includes being able to read clearly what exists and being able to read clearly what is not represented.

The breadth of what is included in the book for sure is a good starting point for many discussions. At some stage, though, these discussions would need to address what’s missing, why it’s missing, and how what’s missing can be rectified. Visual literacy is an endeavour, a practice — and not something set in stone forever.

An Educational Archive of 2863 Slides; images collected by Frido Troost; essay by David Campany; 400 pages; Art Paper Editions; 2020

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.