“The photos took place in Kyiv before the full-scale invasion.” The weight of these words, a few pages after the final photograph in Vladyslav Andrievsky‘s District, are hard to assess for anyone not living in Ukraine, anyone not experiencing the daily threat of being torn to pieces by russian missiles, drones, or bombs.

To what extent my knowledge of the war influences my read of the book I can’t tell. Am I reading too much into these photographs taken from 2017 until 2022 when I claim that there is a pervasive feel of dread, of something not entirely benevolent that might happen at any moment?

Perhaps.

And yet, I maintain that what I see is real. I could pinpoint it in the photographs and their interplay, which, given the way visual books work, would be a lot easier to demonstrate by showing it in person than by writing about it.

Alas…

It feels flippant to compare attempting to find one’s footing as a young person with living in a country at war, even as youthful drama often yields the kinds of exaggerated situations that life under bombs will bring naturally.

But bombs might bring death while the drama of youth only brings disappointment — and maybe some hurt.

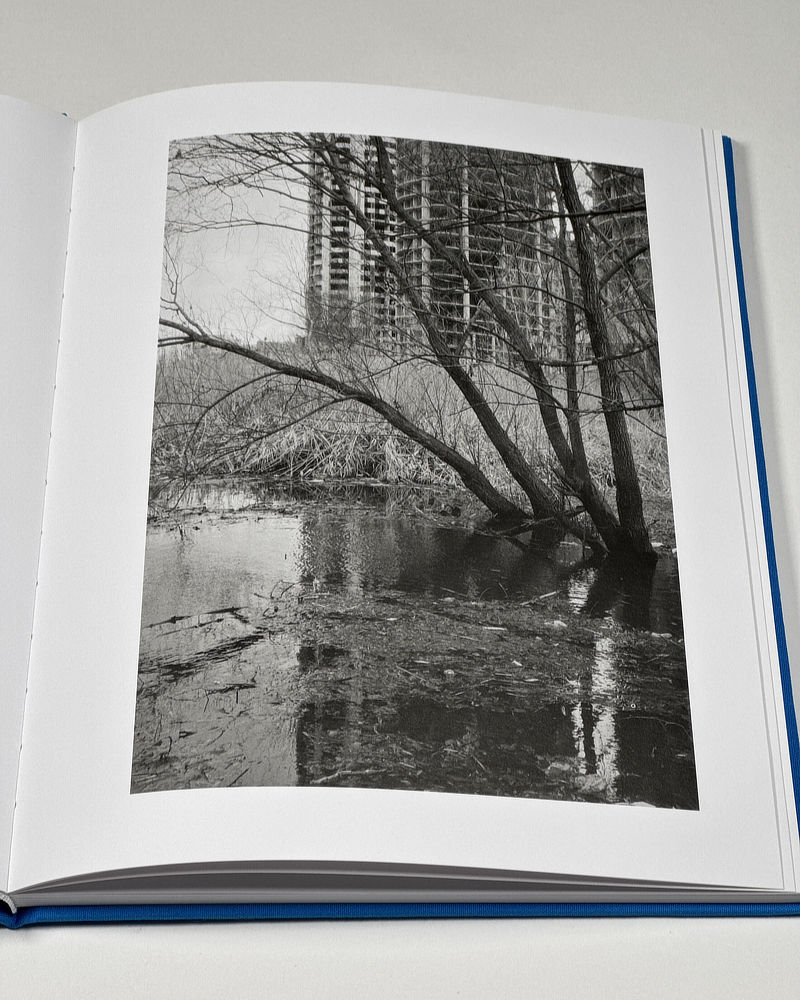

At its core, District centers on growing up among the large multi-story apartment buildings that are so pervasive in those regions of Europe that previously were under Soviet rule/occupation. Mass produced and cheaply built after World War 2, they served an immediate need for housing, and at least initially, they brought forms of comfort to places that had not had them before.

With time, however, their increasing dilapidation not only served as a metaphor for the system that had created them, it also brought daily misery to those forced to live inside them.

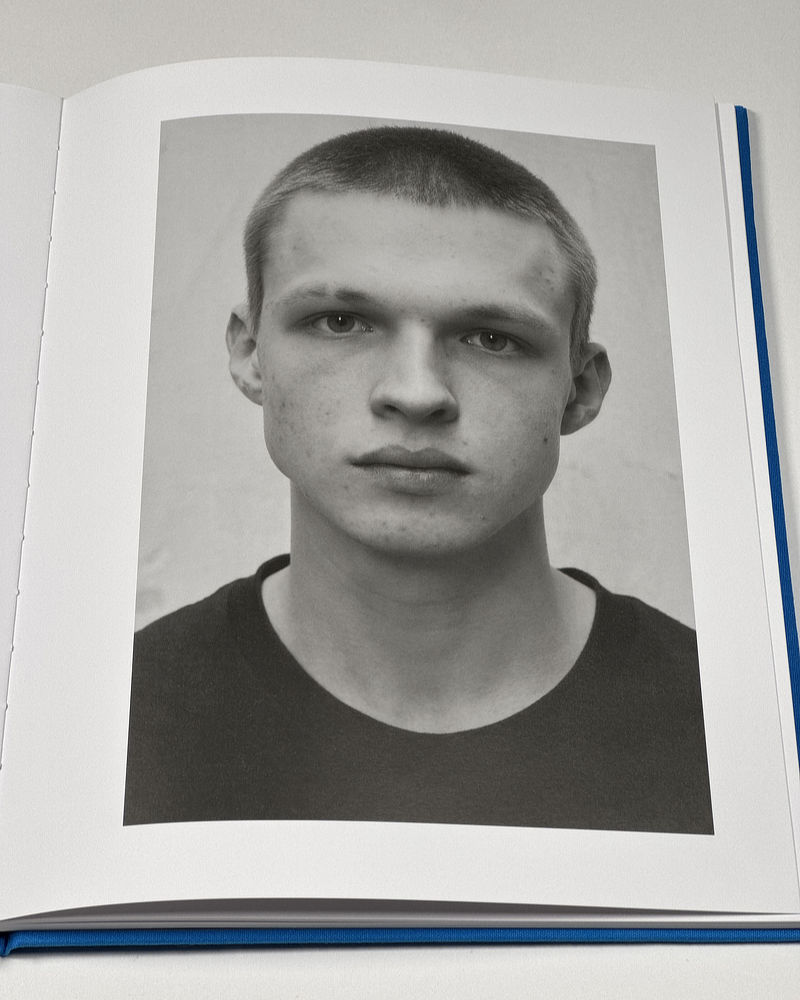

And their anonymity stood in the way of what young people strive for the most: a sense of belonging to a unique community, a sense of feeling seen (while not being seen too much).

District is filled with depictions of those buildings and their surfaces. It’s difficult not to imagine being among them on a cold day, with the wind howling and diversions being absent.

Seen that way, the book’s story (if we want to use that word) is one that is experienced all over the world and that could have been told anywhere.

I’m writing this not to diminish Andrievsky’s book in any way. Instead, and this is important to note a few days after the current US president and his lackeys betrayed Ukraine, we need to see the people living there in the same way we see our neighbours across the street: as human beings who are just as deserving of safety, protection, and our care as we are.

Their stories, in other words, are our stories as well, even if the details might differ. That young people growing up in banlieue (to use the French term that seems most well suited to describe what I’m after) all face the same struggle is worthwhile mentioning; of course, it’s only the ones in Ukraine (or Lebanon, Gaza, and elsewhere) who also live under the threat of death arriving anonymously from the skies.

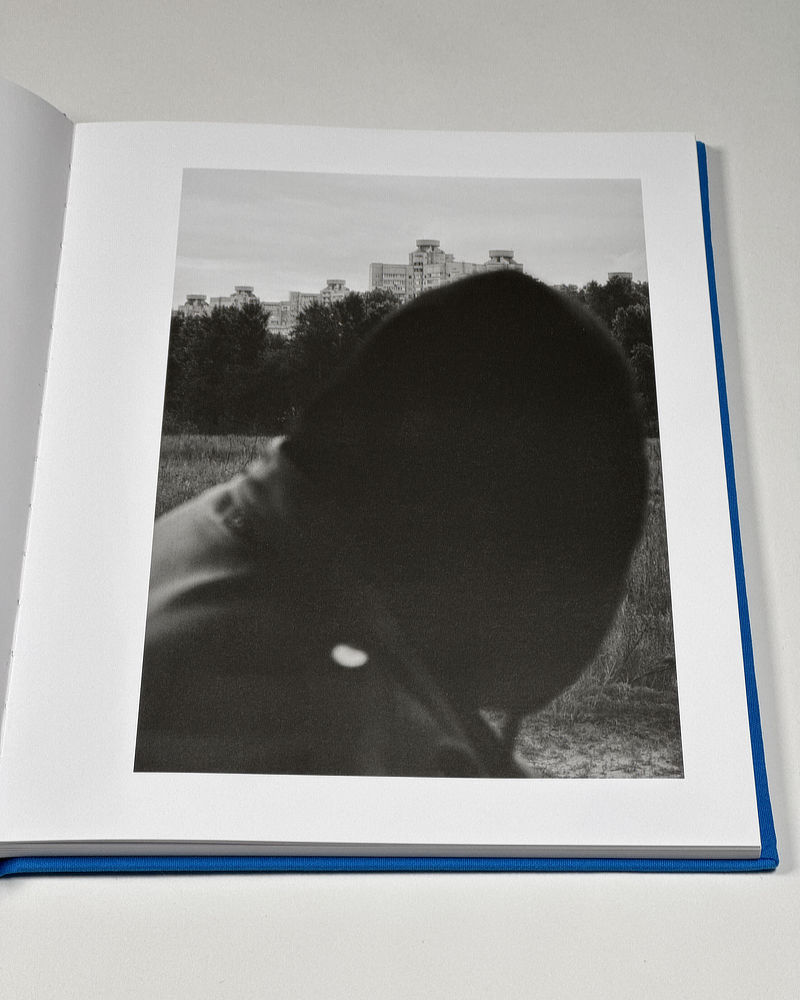

District breaks with the conventions of telling such a story through its inclusion of a very smart detail. The bulk of the photographs are in black and white. But there is a small number of colour pictures: a view of the sky, with the sun coming out behind an impossibly dark cloud. The pictures appear to have been taken moments apart, and there is more and more sun.

More and more sun. It’s not clear whether the hooded figure who in the first photograph gazes towards apartment towers in the distance will notice it. But in the final picture in the book, his head has turned, and there are traces of a face to be seen.

District shows a gifted photographer at work, one of a number of young Ukrainians who now are slowly becoming more well known outside of their home country.

It’s a brooding book for all the reasons I outlined above, but who am I to tell a young person not to brood? (Especially since I’m still spending so much time brooding myself.)

Recommended.

Слава Україні!

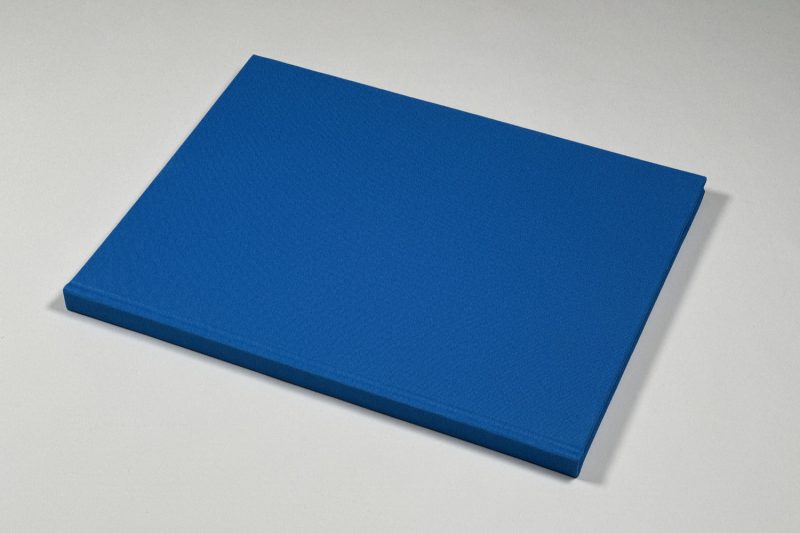

District; photographs by Vladyslav Andrievsky; essay by Olha Pavlenko; 100 pages; Syntax contact; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!