A lot has been said and written about the civil unrest that has gripped the United States at this particular moment in time, much of it smarter than anything I can hope to aspire to. But maybe I can contribute a little by giving my impressions concerning photography and its larger implications, singling out one particular photograph.

(To be honest, I don’t know if I have succeeded in expressing my thinking clearly with the following. Sometimes, what is so clear to me in my mind at the same time is very hard to be clearly put into words.)

The list of names of African-American citizens murdered in cold blood by those who drive around in cars that often spot the slogan “to protect and serve” is long. Its length is made a lot more worse by the fact that such murders usually end in an acquittal in court — assuming there even is a court case after police departments’ “internal investigations”.

It’s important to realize that for many of those on that list there isn’t just a name. There also is a video taken by someone who happened to be on the scene. We have been able to watch the murders of George Floyd, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Philando Castile, and many others with our own eyes. We’ve heard their voices as they were killed: “I can’t breathe!” We’ve heard how they pleaded for their lives, which were then callously taken away.

These videos — and associated still photographs — make the talking point that trust in images has been eroded by digital media look silly. We can see with our own eyes! And we take the veracity of these images over the press statements released by police departments — and mayors who, more often than not, side with the police, regardless of what political party they belong to (systemic police violence in the US has broad bipartisan support).

A brief aside: there is an article yet to be written about how the United States’ recent history has been understood and defined through relatively short film clips, clips that for better or worse have become integral parts of the public’s visual culture. The video showing the murder of George Floyd has now been added to this library (if we want to call it that), to exist alongside those of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the moment Neil Armstrong descended from his capsule onto the moon, and others.

Once protesters flooded America’s streets to yet again demand change, to once again assert the fact that Black Lives Matter, hoping that this time there will in fact be a change, a large number of additional images arrived, videos and still photographs from the many demonstrations. I was going to write about those pictures, but John Edwin Mason just did so in a stellar article that for sure you’ll want to read (if you haven’t done so already).

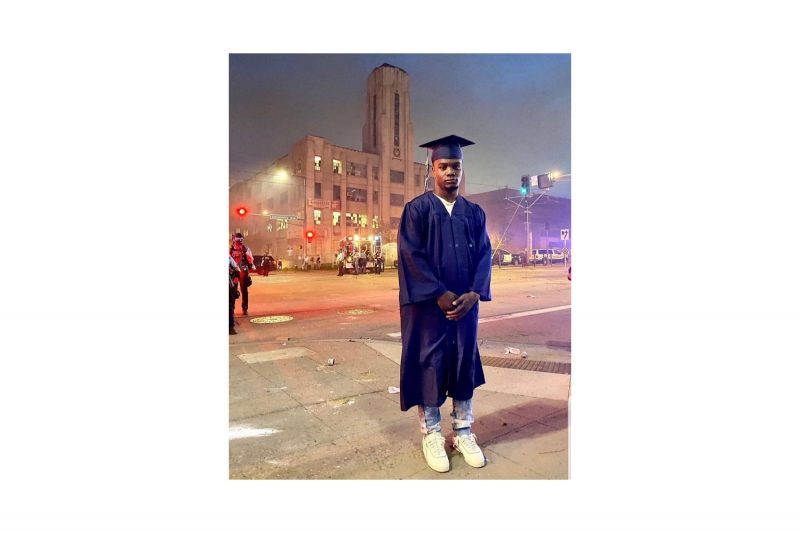

In his article he covered the photograph of Deveonte Joseph, taken in Minneapolis by Nathan Aguirre. The photograph was also discussed by in a very good article by Connie Wang that includes a lot of details. Read it.

This particular photograph stopped me in my track when I came across it. I think it’s extraordinary, and I feel the need to tell you why.

In their articles, Mason and Wang discuss a number of photographs made by news photographers or photojournalists. In particular, Mason discusses how these pictures work and why some of them feel problematic, despite the fact that they are all very good pictures.

Photography made of protests have a long history, and so have the various categories they can be put into, the types of things or events they show, and how they do that. Often, it is simple to project readings onto such photographs that can run counter the ideas of the actual protests.

Typically, the most dramatic pictures, the ones showing the looting or some fire burning somewhere, are being picked by editors to accompany articles about protests. I’ll have to admit that I’m weary of protest photographs because of this dramatization. Aguirre’s photograph was so interesting and mesmerizing to me because not only is it such a perfect picture, it also completely stays away from any dramatization.

In fact, it manages to be two types of pictures at the same time. When I look at this photograph, I see two stories — that typically employ very different photographic approaches — come together as one. I see protest photography, and I see the type of portrait photography done at the occasion of graduation ceremonies.

This observation itself is very obvious: that’s what this looks like. But this is not something we see running through the history of protest photography. This is not your standard news/photojournalistic ware. It’s more than that. It is a photograph of an event as much as a photograph that speaks about the larger issue.

In my mind, there’s a duckrabbit effect going on. One moment, I see a photograph of a protester. The next moment I see a young man who like all of his peers was robbed of the graduation that I’m sure he had been looking forward to for a long time. These two aspects connect, in much the same way as there is civil unrest in the US while there also is a pandemic raging (the combination, one must fear, will lead to explosion of new Covid-19 cases).

Deveonte Joseph has been robbed twice. All of his white peers were robbed of their graduation ceremonies, of being in the same room together with proud family members, to receive their well earned diplomas. The same is true for all students who are people of colour (poc).

But much like his poc peers this young black man has already been robbed of enjoying the same rights, the same privileges that his white peers get to enjoy (often without even noticing). On paper, he has the same rights, but in actuality that’s not the case — if it were so there wouldn’t be huge protests. In this photograph, he stands in for all other people of colour in this country, whether they’re students or older.

Back in (then West) Germany I didn’t graduate from high school wearing cap and gown. I have to become accustomed to their role in the United States, a role that has very little to do with the associations I originally made based on German history (where such caps and gowns had been removed to break with traditions that had not served the country well).

I don’t know to what extent Americans would see it this way (I never asked), but I see this outfit as a promise to those wearing it: you not only succeeded with your studies, you also have all the opportunities that we as a society can offer you.

Seen that way, cap and gown here remind us of the fact that all students graduate with dreams of making a good life: of going to college, getting a good job, etc. Historically speaking, we know that the promise I spoke of is usually very hollow if you’re a person of colour. With the protest background in the picture, cap and gown here ask us to consider whether we want the promise to remain hollow.

So this is a picture or a particular moment in time, a young black man in an American city in the middle of a civil unrest. But it also is a picture about the fact that behind all the names in the news, the names of all those black men and women killed by the police, there were all those aspirations and dreams killed with them.

When I first saw this picture, I felt that by posing for this picture, Deveonte Joseph was imploring us to think of the dreams and aspirations every human being has, regardless of the colour of their skin. For me, his cap and gown are the equivalent of the “I am a Man” signs held by protesters in 1968. James Douglas, a sanitation worker, spelled it out: “we were going to demand to have the same dignity and the same courtesy any other citizen of Memphis has.”

The same dignity and the same courtesy, the same rights — the call for that is in this pictures itself, much like it is the protesters’ demand.

Nathan Aguirre’s photograph of Deveon Joseph is a call for a just society that finally fulfills the promises made to all of its members.

There is a GoFundMe fundraiser for Deveonte Joseph, intended to help this young man with his next steps. I hope you’ll consider chipping in.