Now that I have spent decades looking into the past of the country I was born in, Germany, I’ve come to realise that the greatest threat to humanity is not posed by lunatics such as Hitler, Goering, or any of the other main characters from the Nazi era. These people undoubtedly were evil in the most basic sense of the word. However, without the active help of not only perfectly ordinary people but also, crucially, of a group of highly talented individuals whose moral compass was completely absent Hitler would have been unable to lay waste to an entire continent and kill millions of Jewish people in an industrial fashion.

To begin with, there are the likes of Adolf Eichmann, capable administrators who will apply their organizational skills to any task they’re given. When pressed, they will say that they were merely “following orders” and thus somehow are not responsible for the consequences of their deeds. And then there are the likes of Albert Speer or Wernher von Braun who operated at higher levels but who also were cut from a different cloth than Eichmann. Or take Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl. All were extremely gifted people who happily put their talents to use for their regime’s murderous purposes.

After the war, surprise!, surprise!, they claimed that they had not known about the crimes they had contributed to. Obviously, this was the default defense for most Germans. But especially with individuals who were that gifted at solving even the most complex problems, the excuse rings particularly hollow. Von Braun was smart enough to develop the most advanced rocketry the world had seen until then, but somehow he was not smart enough to literally see the slave labour that was used to produce it?

After the war, Speer spent two decades in jail. Von Braun, in contrast, ended up as an employee of the US government, developing its space program. It is von Braun who thus makes for one of the most interesting cases. Here is why. Monstrous lunatics such as Hitler or, to use a contemporary example, Vladimir Putin are fascinating because they are obviously completely evil. At the same time, they are so different from most people’s lived experience that there almost appear to be from another planet (or from a movie — the go-to image people often use). In contrast, people like Eichmann live in our midst.

People like Speer or von Braun not only live in our midst as well, they are also very much visible. They’re the brilliant operators that any country relies on to keep it running. Which is fine — there is nothing wrong with brilliant operators per se. The real problem is twofold. First, it’s how morally compromised they can be (and often are). But second, and this is what really gets me, is that we don’t appear to have a problem with that. Let’s use a contemporary example. John Yoo, the person who wrote what became known as the “torture memos” still teaches law at UC Berkeley.

One of the most disturbing aspects of all of this is that in our democratic societies, we have no problem with employing people whose moral compass appears to be completely broken or absent, and we allow them to do their work for us even when their problematic past is openly known. Or we lionize billionaires who very obviously and openly voice their contempt for the democracy we live and act accordingly.

When I grew up, the standard tale was that Nazi Germany had been completely different than the West Germany I was living in. I was basically led to believe that after the war, the Nazis had all magically vanished into thin air. I was unable to understand how this could have happened. Now, I know that I had been lied to left and right. Now, I know that perfectly ordinary people not only have the capacity to do evil, they also have the capacity to tell themselves (and others) that there’s no problem with that.

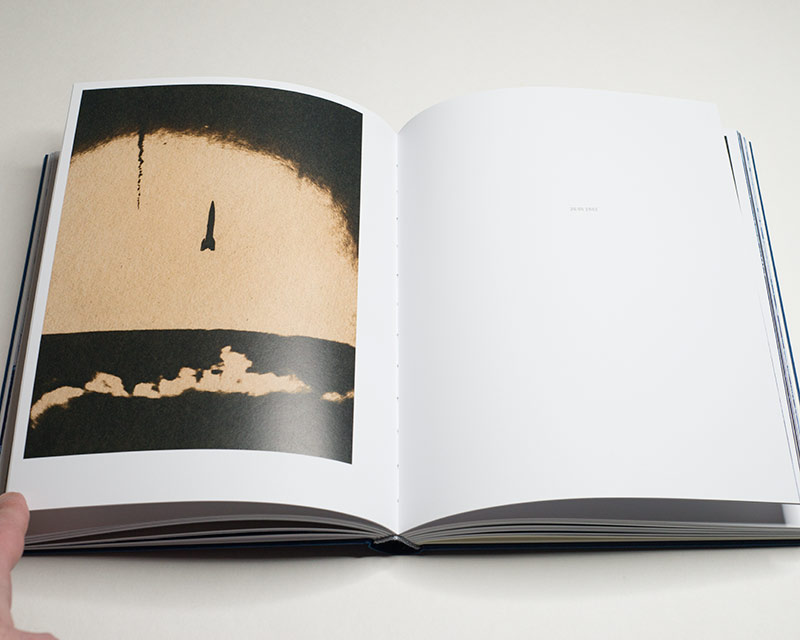

The life and career of a Wernher von Braun provides a perfect example. If you don’t know much about him, you can learn a lot more from a new book by Lewis Bush, Depravity’s Rainbow. The book basically chronicles the man’s life story. But it does so in a very smart way that helps bring focus to von Braun’s life, his work, and the way two very different countries happily used his expertise.

In a nutshell, the life story is wrapped onto itself. As a viewer, you see von Braun’s greatest US success, the successful landing on the moon, and his birth and upbringing first. As the book unfolds, it moves back in time for the US space program and forward in time for von Braun’s German life. This way, two seemingly very different aspects of the man’s life are being brought together, as are the ways the two different countries he lived in engaged with him. Later rocket launches now sit next to earlier ones, and a variety of other material is brought into connection.

Late in the book, you get to see a copy of von Braun’s ID from Nazi Germany’s Oberkommando des Heeres (Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht), issued in early 1945, followed by an ID of the US Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Huntsville, AL, issued in 1949. It’s the same man, the same face, staring into the camera. The switch, it would seem, was easily made. Just a few pages later, the final photograph in the main section of the book shows dead inmates at the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp where von Braun had had his rockets built.

Apart from von Braun’s life work itself, there obviously is another topic that is being explored in the book, namely the problem of dual use. Actually, as I’ve argued above, the problem isn’t so much dual use itself, the fact that the same technology can be used for productive and destructive purposes. It’s that most people don’t appear to have a problem with that. But mine might be a different interpretation than Bush’s. There is an excellent essay at the end of the book in which he dives into the details of many of the aspects I alluded to here.

Depravity’s Rainbow combines a lot of archival material with photographs taken by Bush in various locations that played a major part of von Braun’s life story, in particular locations in Germany that probably are mostly only known to people looking more deeply into the country’s history.

The book makes for an excellent example of what at some stage I termed the research-based photobook because it manages to present a rather complex story in an engaging and insightful fashion, focusing both on space programs and the moral inadequacies of an incredibly gifted human being.

Bush has his reasons for using the cyanotype process for his imagery. I’m not sold on those. I find the blue and brown tones distracting; but that’s just a minor quibble.

In any number of ways, the life story of Wernher von Braun has lessons for us today. In Ukraine, for example, Russian forces are using contemporary missiles in the V2 fashion, indiscriminately bombing civilians in Ukraine. At the time of this writing, the latest example comes from Sloviansk where one dozen people were killed in their apartment buildings.

Putin, a cartoonishly evil character, would be unable to wage his war without all those people who have no problem with sending off their missiles (many of which originally were produced for air defense). I’m sure that when this is all over, they will all say that they didn’t know anything or that they couldn’t have done anything. I’ve heard all those excuses in the different context of Germany already.

One final comment. Depravity’s Rainbow was self published. Making a book is a difficult task even when working with a publisher. Doing it on one’s own is even harder. Getting a copy of the book will not only add a real treasure to your library (at £40.00, the book is a total steal), it will also support its maker directly.

Highly recommended.

Depravity’s Rainbow; photographs and material collected by Lewis Bush; essay by Lewis Bush; 250 pages; self-published; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!