There always is the curse of that one famous thing – album, novel, photobook, movie. Then what? I suppose the choice is to either agonize over your success so much that you kill off your own creativity or to simply do something else. (Let’s face it, though, the second-album problem really is only a problem if you agonize over your choices.) In this day and age, where the hype around photography and/or photographers has reached levels previously only witnessed in the larger sphere of popular culture, this decision increasingly has to be faced by those who, well, strike the jackpot. Cristina de Middel is one of those photographers. Her self-published book The Afronauts has quickly reached cult status, and deservedly so. If you take away all the hype, it is an incredibly endearing book, a prime example of how you can truly bring to life photographs in book form (I saw the work on the wall of a gallery, and I didn’t like it nearly as much).

When I met Cristina last year in Ireland, I was a little bit surprised to see her so unfazed by all of this. Or maybe unfazed isn’t the right word. She clearly enjoyed the success and having an opportunity to show the work in so many different places, to so many different people. But somehow, it didn’t look like she was overly worried about what to do next. In fact, when we spoke, she told me about what she had been working on, what was to be the next book.

Doing something like The Afronauts would have been incredibly tempting. But once you walk down that path, things can turn into a shtick pretty quickly. And there’s no shortage of photography that has become a tiresome shtick, isn’t there?

But of course, at the end of the day a photographer has to do what s/he has to do. It’s not up to the public, certainly not up to critics, to demand anything, the hype over a body of work notwithstanding. As a photographer, you really want to do what feels right, which, I think, includes doing something that challenges you at least to some extent.

Cristina told me about a trip to China that had resulted in photographs. And she wanted to incorporate those photographs into a copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, the “little red book.” With Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin‘s Holy Bible lying on a table nearby, I asked her how about that. Of course, there was absolutely no need to ask that question, given that two different books made by two different groups of artists in all likelihood will be quite different. But then, adding pictures to a very specific culturally loaded book – in how many different ways can you do that?

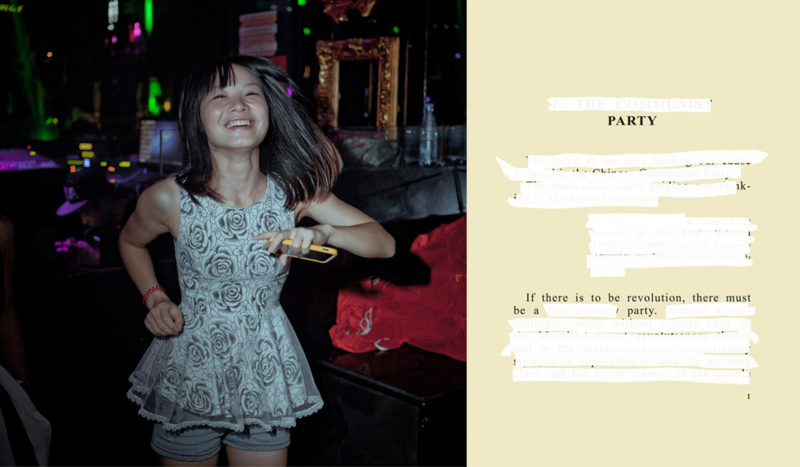

Turns out, if you have two such books, you can do it in two different ways. I’m glad that Cristina did not do what a lot of people (me included) would have done when she learned about Holy Bible: not pursue her idea. So here is Party. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (or “Quitonasto Form Chanmair Mao Tungest” as it says on its cover).

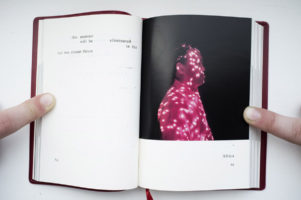

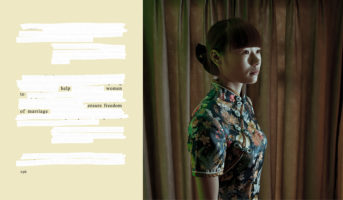

Holy Bible and Party roughly follow the same ideas: take a book and add pictures to it. But there are crucial differences as well. Holy Bible (which I reviewed here) uses archival imagery from the Archive of Modern Conflict. In contrast, in Party, Cristina used her own photographs, taken on a trip to China. In Holy Bible, specific phrases are underlined and matched up with photographs. In Party, the vast majority of the text has been covered up (with white correction fluid), to leave behind short phrases. In Holy Bible, photographs are superimposed on the original text. In Party, they’ve been added as separate pages.

Holy Bible is a profoundly political and ultimately very angry book. Party, I’d argue, ultimately is equally political, but at the same time it’s often almost dada.

If you know about the history of China under Mao, you know about the millions of people who lost their lives (see, for example, Jun Chang and Jon Halliday’s Mao: The Unknown Story). How do you then adequately go about the “little red book”? Well, for example, you white out most of the text so that what is left is “people can talk much nonsense” (p. 212), “the real heros are ignorant” (p. 118), or “intellectuals tend to be thinking” (p. 292). I’m tempted to think the artists organizing Berlin’s 1920 Erste Internationale Dada Messe (First International Dada Fair, see this article), people like Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, or John Heartfield would have accepted Party in a heartbeat.

Given our times have become so strange, given our responses to all these problems we’re dealing with right now appear to have become so inconsequential, bringing dada back seems like a pretty good idea to me.

Party. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung; photographs by Cristina de Middel; original text by Mao Tse-Tung, heavily edited by Cristina de Middel; 306 pages; Archive of Modern Conflict in association with RM Verlag; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 5, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 4

Ratings explained here.