If we are going to be remembered at some stage in the future, in all likelihood it will be one thing or aspect out of the many others that constitute our lives. In the case of Dorothea Lange, that’s the photograph known as “Migrant Mother”. The image has become iconic, meaning it has transcended the narrow confines of photoland and is now part of the collective myth that underpins the United States. The woman in the photograph, Florence Owens Thompson, has become a cypher — as has Lange herself.

This particular photograph aside, one of the main reasons for why photographers usually end up as these rather one-dimensional creatures is because there usually is so much control exerted over their legacy, meaning both their work itself and their image. More often than not their estates control every aspect of what can and cannot be done with the photographs they own, essentially cementing narrow views and preventing genuinely new discoveries or re-interpretations.

Of course, this system is not restricted to photography, but I do think it’s particularly harmful here: after all, for most photographers, there exists a large pool of unknown work in the form of pictures that were never used, never seen before. With access to such material usually being very restricted, estates (in collusion with curators) guarantee that most photographers are never being re-discovered. Instead, they become part of some sort of canon, while also becoming more and more irrelevant for a contemporary audience.

In the case of Dorothea Lange, the Great Depression photograph “Migrant Mother” speaks of a time long gone while the associated myth makes it even harder to create connections to our present time. After all, what does Florence Owens Thompson have to tell us for our own neoliberal era, where more and more people have to rely on working two or three poorly paid jobs? In much the same way, Lange’s own sensibility has disappeared as well — the things she might have cared about, things that would be communicated to us through her work, assuming we’d have the right access to it.

Photographs are only alive if they are allowed to exist in new contexts, contexts that possibly force a new meaning onto them. Where such new contexts are not a chance to arise, photographs wilt like flowers deprived of water. The history of photography essentially is mostly a collection of dried flowers that have become too brittle to exist as anything other than something to be gawked at, something that doesn’t speak to us any longer.

A new book entitled Day Sleeper now lifts Lange’s work out of the stasis it has found itself in for too long. For the book, Sam Contis used the archive housed at the Oakland Museum of California (plus images from the Library of Congress and the National Archives). In her afterword, Contis writes that “[t]he more I spent looking through her contact sheets, the more I started to feel an unexpected kinship. […] I formed the idea of making a book that would show her in a new light and also reflect a shared sensibility.”

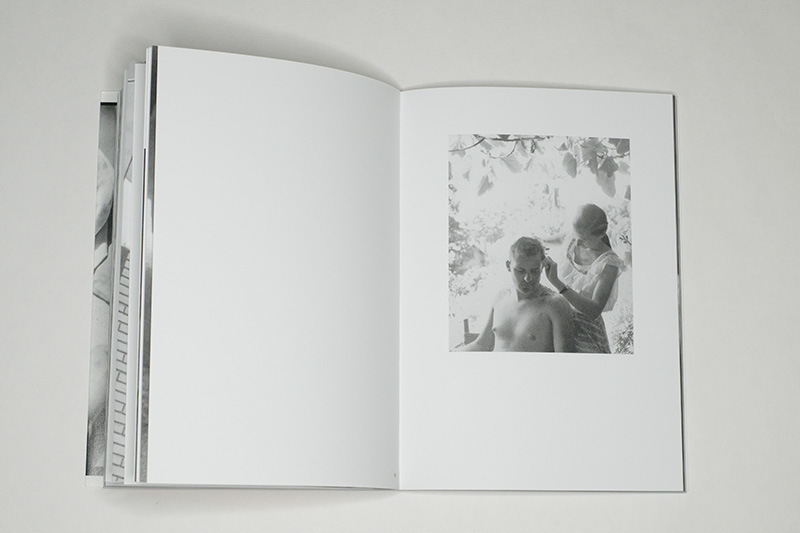

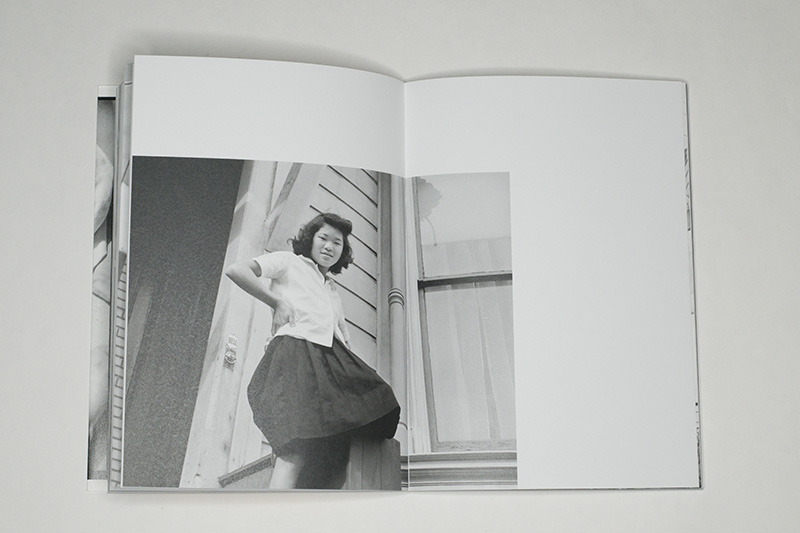

There are two words here that I find absolutely crucial, namely kinship and sensibility. Through her deft choices, Contis has allowed the rest of us to partake in her own discoveries, essentially giving Dorothea Lange a contemporary life, a contemporary incarnation. To begin with, we get to see aspects of Lange’s work and personality that I don’t think we were familiar with. A touching tenderness pervades the book. With very few exceptions — a crucified eagle being maybe the most drastic example — the photographs are very tender and far from the open expressiveness found in “Migrant Mother.”

At the same time, because visual markers of time are largely absent these people and places from the past could have been captured just the other day somewhere. It is tempting and easy to think of Dorothea Lange as that Great Depression era photographer. But underneath, there was a human being whose aspirations, dreams, and feelings were at least in part shared by Sam Contis. And it is those aspirations, dreams, and feelings that are being communicated by Day Sleeper, allowing for Lange to reemerge in a new light.

If anything, the book demonstrates how much can be gained from the radical reinterpretation of a photographer’s work that we are given here. These photographs, taken decades ago, speak to us about our times. It is as if they were being made for us, to be seen by us, to have their maker urge us to look at this world. And it is Contis who we have to thank for this; after all, she could have decided to create just another edit of the work that would follow an art-historical approach, picking different photographs of already existing ideas.

Despite the lack of the open expressiveness we might have come to expect from Lange, the book clearly is not without an edge. There is, as I noted already, the photograph of the crucified eagle — the bird of prey strung up on barbed wire. I think this picture is absolutely essential; had it not been included, it would have been too tempting to dismiss the book as a contemporary apolitical exercise. And there are other photographs that hint at something being profoundly wrong in the land. What is wrong is not being spelled out — does it have to be? Isn’t it completely obvious if you just look around?

I’m hoping that Day Sleeper is going to become the seminal book it deserves to be, followed by many others in which someone will reinterpret the work of a photographer long gone. There are, after all, many artists whose work is in dire need of a reinterpretation, of a rediscovery. As this book demonstrates, it’s not just the artists who benefit from such an effort, it’s all of us.

Highly recommended.

Day Sleeper; photographs by Dorothea Lange, edited by Sam Contis; MACK; 2019

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.