How can pictures and text interact? How do they function sitting next to each other, sitting with each other? These are complex questions for which some answers already exist. For example, there’s the standard photojournalistic model in which short factual text supports a picture in the form of a caption. This model, and the somewhat more relaxed one used for documentary photography, accepts the shortcomings of both text and pictures, and it has them each operate within their own boundaries.

And then, of course, there’s the struggle between text and pictures, which more often than not is perceived as a competition, if not a conflict. Many photographers don’t like working with text because they are afraid it might take something away from their pictures. To some extent, I understand what this might be getting at; but at the end of the day, the form a piece of art can take should not be driven by one’s hang ups or insecurities, should it?

Consequently, if you want to use text next to photographs, you will have to understand what both do — can do as much as cannot do. This requires a solid understanding of both — text and pictures. You understand pictures by looking at as many as you can with an open mind and a sensitivity for what is being conveyed (and how). The same is true for text: you understand text by reading a lot of it, again with an open mind and with a sensitivity for what is being conveyed (and how).

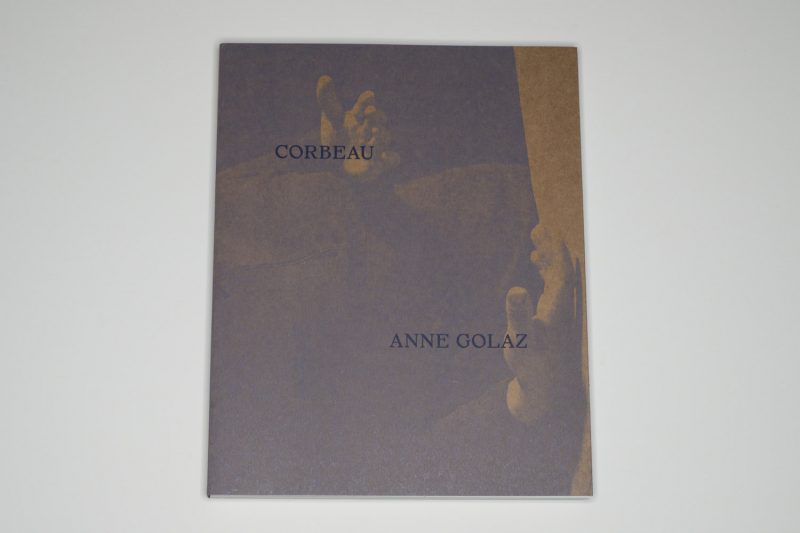

In many ways, Anne Goldaz‘s Corbeau (which was already published in 2017 and which has been lying right next to me ever since I received it) should serve as one of the prime examples of how text and images can interact very successfully. In a nutshell, the book centers on familial obligations, here in the form of a family farm that is to be passed down from one generation to the next (more accurately from a father to a son).

To be perfectly honest, I grew tired of seeing family projects probably already a decade ago. We all have families, and all families have problems. OK, fine. I also have no problem with anyone working through their family history and/or problems photographically. That’s cool. The main question for me is where or how any family project becomes art — that, after all, is not a given. Most family projects remain basic descriptions of situations thousands of people find themselves in, and I personally don’t look at art to have my expectations fulfilled.

So I was a bit reluctant to engage with Corbeau when I received it. To pretend otherwise would simply be disingenuous on my part. The book won me over — this was actually a slow process — not just because it is done so well. It’s mostly because while ostensibly centering on family, its real focus is the universal struggle to make sense of one’s life in light of the various forces that keep pulling one into different directions. How does one deal with that?

Obviously, there is no simple one-size-fits-all answer here other than paying careful attention to one’s own needs as much as to others’. And that’s not much of an answer, it’s more like the very first step in a process that has many more, with none of the following ones being provided. So it’s like art or rather good art. Good art doesn’t provide answers, it might not even provide solace. All it can do is to make one more aware of one’s own fallibilities, of one’s own being fragile and vulnerable, to then nudge one to make a move.

In Corbeau, this is done through a smart combination of images and text. Both come in a variety of forms — there are different types of images (photographs, drawings), there are different types of photographs (archival and more recent ones), there are different types of text (poems, brief short-form essays, text messages, etc.). Given the variety of the source material, it actually shows the vision and strength of its maker that the book succeeds so well.

But, as I noted above, as a viewer/reader, you’re not going to fully understand the book in one sitting. With picture-only books, this typically is seen as just the way most of those go. With text added, I think there is the expectation that one ought to get it in one go — after all, that’s exactly why and how text was and still is used in many books of such type: the text is intended to make the whole palatable and easily understandable (c.f. pretty much all classic photojournalistic books).

Given that the text here does not merely play the role of supporting cast, this expectation needs to be dropped. The book works so well because it unfolds with time, allowing the viewer/reader to dive deeper and deeper into its layers. It’s a complex book, but it’s also an emotional, felt book. In fact, that might actually be the most important achievement here, namely that the viewer is made to feel something.

Highly recommended.

Corbeau; photographs, drawings, and text by Anne Golaz; text by Antoine Jaccoud; 196 pages; MACK; 2017

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.1

Ratings explained here.