Late in 2022, Michael Schmidt‘s Ein-heit, which had been long out of print, was reissued. The book is not only a masterpiece of photobook making, it also directly addresses what has remained Germany’s most monumental historical event over the course of the past 50 years, the unification of West and East Germany. With the many historical images used throughout the book, vast parts of the country’s history in the 20th Century are addressed, including World War 2 and the Holocaust. Furthermore, the different types of government under which Germans lived can be found in the book as well.

Up until Schmidt’s Waffenruhe — published roughly a decade earlier — and the 1996 Ein-heit, unlike their artistic peers — writers, painters, movie makers — German photographers had largely avoided dealing with their country’s history. How or why I still don’t understand, and I find it reprehensible. Unfortunately, Schmidt died in 2014, meaning that there is no opportunity for me to speak with him about these particular books and his thoughts about the country and history they were dealing with.

Thomas Weski was a close collaborator of Schmidt’s, and he has been in charge of the Michael-Schmidt-Archiv. He curated the retrospective that traveled to a number of major European museums and he produced the catalogue. Thomas also initiated the re-release of some of Schmidt’s books, of which Ein-heit is the latest example.

Given how close they were, I approached Thomas to see whether I could get insight into some of the things I was interested in. He kindly agreed to speak to me over Zoom in February this year. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity, and it was translated from its original German.

Jörg Colberg

I am currently working on a project that revolves around German photographers who have dealt or are dealing with contemporary German history. After the Second World War, there were writers like Heinrich Böll or painters like Gerhard Richter or Anselm Kiefer who dealt with German history. In photography, however, for a long time nothing happened. I have always been curious about that. Michael Schmidt was one of the first and most important photographers to deal with this history in Waffenruhe and Ein-heit. You knew Michael. You are also mentioned in the book. That’s why I wanted to talk to you.

Waffenruhe was published in 1987. Two years later, in 1989, the Wall came down. Suddenly, the book had become something completely different. It almost became a document because it dealt with something that had now ended. How did Michael react to the fall of the Wall?

Thomas Weski

Unfortunately, I don’t know where Michael was when the Wall fell. So I can only speak for myself. I was very surprised the morning after the Wall came down, because I hadn’t even noticed it the night before. At breakfast I followed the coverage first on the radio, then on TV, and of course later at work it was the main topic. For the time being, Michael had lost the topic of his life with the fall of the Wall.

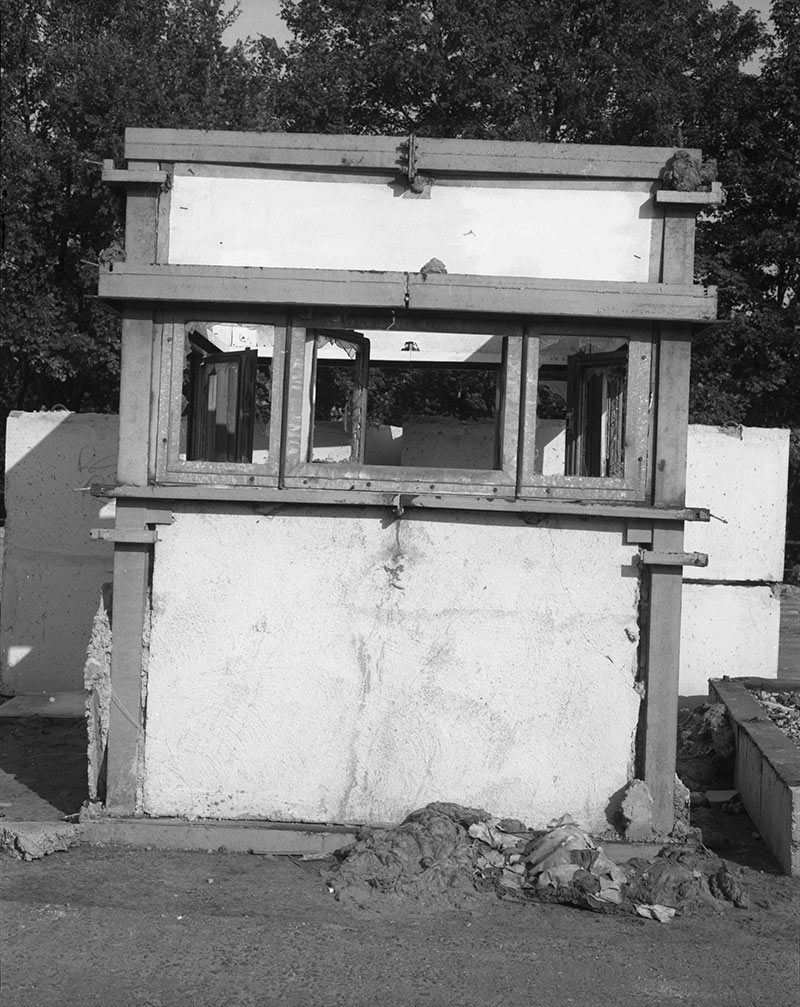

However, he did photograph the process of change, the signs of dissolution, and the visible removal of the border installations in Berlin. He spent a lot of time in the former area of the Wall, now an empty zone in the middle of the city that had a dystopian character all of its own.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, 89/90, ©Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, 89/90, ©Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, 89/90, ©Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

From this work, the book 89/90 emerged. However, he only published it in 2010 for the exhibition at the Haus der Kunst, which I curated. So there was a delay of 20 years. Before that, the work lay dormant in his archive. But in parallel to the project he later called 89/90 he started working on Ein-heit. He immediately took advantage of the situation by traveling to East Germany to photograph there. He also went to East Berlin. There were some photographers who regretted that the Wall had fallen. That was not the case with him. But I don’t really have a clear answer for your question.

I have always read Waffenruhe as on the one hand a documentary work describing the past. On the other hand, though, Waffenruhe voices a premonition in addition to an atmospheric psychogram of the still-divided city. I find it interesting that he addressed this theme with its different aspects at this particular point in time in a way that goes beyond a depiction of the concrete situation and that formulates something like an artistic conception. I always had the feeling that West Berlin photographers tried to photograph the city without the Wall in order to achieve something universal, metropolitan, rather than something specific, uniquely historical. There were only a few photographers who dealt directly with the Wall. For example, at the end of the 1970s, the Berlin photographer Hans W. Mende walked and photographed the entire course of the Wall in his project Grenzbegehung – 161 Kilometer in West Berlin [Border Walks – 161 kilometers in West Berlin]. But in the world of photography, apart from Michael no one dealt with the psychological significance of this dividing wall. In literature that did happen, I’m thinking of Uwe Johnson or Peter Schneider, for example.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Waffenruhe, 1987, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

JC

Michael always worked a focus on on projects, didn’t he?

TW

Yes. In the catalogue of the retrospective you can see that well. There, we listed the various groups of works chronologically. At the beginning of his photographic work there were commissions. Michael adopted that structure for his artistic work. He always worked on very clearly defined projects that were limited in terms of time and topic. He maintained this way of working, which also gave him a structure for his everyday life, throughout his whole life.

For each project, he changed or evolved the particular method he used to approach the particular subject matter photographically. This is an aspect of his work that younger photographers find interesting. It’s a constant pulling back, questioning, finding new approaches, and not an implementation of a successful method all throughout one’s life. It’s taking risks and accepting failure — otherwise, there is no growth of the artistic work itself. Time and again, Michael was impatient and dissatisfied with himself. His goal was to always find a specific and unique form of expression for the themes we has working on.

JC

Working on Ein-heit he added the photographing of historical documents..

TW

There already is an image that shows a photograph of a photograph in Waffenruhe. That was the beginning of his appropriation of images that had already been disseminated through the media. The Siemens Kulturprogramm, for which I was working at the time, financed Ein-heit. I was responsible for the project there, so I visited him regularly to work with him as he was developing the project. There was a phase where he was doing a lot of these photographs of photographs. So I was a bit afraid that he would get stuck in a pure repro project. Around that time, Richard Prince also started talking about sampling, meaning ways of artistically re-appropriating existing visual material in the style of music-production techniques. For a while, I was worried that Michael might be getting into a too fashionable direction. So sometimes I was a little concerned when I went back to Munich from these Berlin visits, wondering where things were going.

I once succinctly called these pictures “repros”. He immediately sharply rejected the notion of reproduction, saying “I take photos of photos. For a portrait I need a person to work with, I need a building for an architectural picture. And so here I use a photo for a photo.” To be honest, in the beginning I didn’t really understand that for him a printed image was part of reality and thus could be a subject for a photograph. He found historical motifs in books he bought at flea markets or second-hand bookshops. He then decontextualised them in his photographs by cropping them extremely in such a way that they take on a completely new meaning and, moreover, are resolved as an image.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Ein-heit, 1996, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

There is an image showing a group of young people. The American art historian Michael W. Jennings wrote about it that they were members of Kommune 1 in West Berlin. But instead it is an FDJ party meeting with young students somewhere in the GDR. Michael took a very small part from of the group picture. This way, the picture opens up. It detaches itself from the historical situation and becomes open to individual interpretation. This is the method that he then applied when photographing photographs.

JC

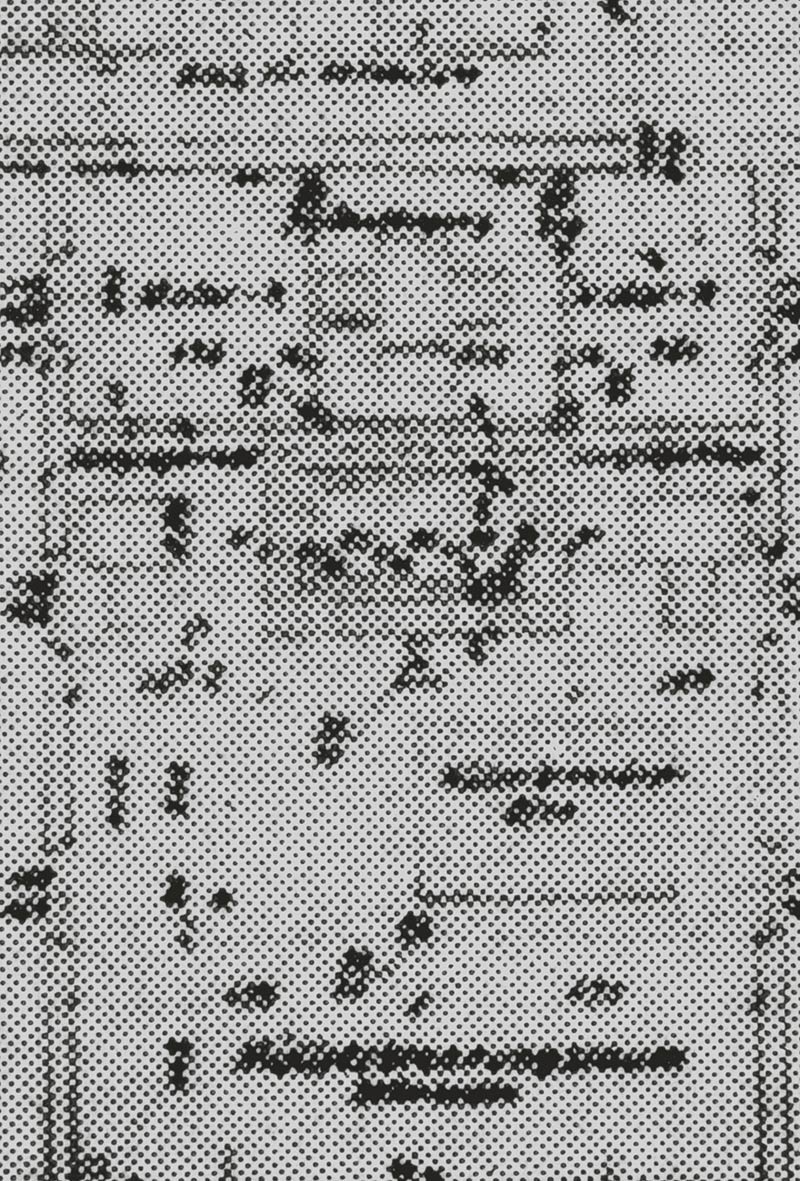

By chance, I was made to look at this the other day. I came across the source material of one of his pictures. The Auschwitz Museum has a presence on social media and shares all sorts of documents and photos there. It showed a blueprint of a crematorium at Auschwitz. I had always thought that Michael Schmidt’s picture — really just a small section — came from there.

This got me thinking. On the one hand, he appropriates the image. On the other hand, it is very important that it is related to Auschwitz. If you don’t see that or don’t know that, then the effect might be completely different. So I was wondering what he was thinking. Did he want people to know that it is Auschwitz? Or maybe not?

Michael Schmidt, Untitled., Ein-heit, 1996, ©Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

TW

Is it this picture? [shows the fourth picture in the book]

JC

Wait, that’s also Auschwitz?

TW

It could be so; I suppose so. It’s a technical blueprint. So there is a suspicion that is triggered. Given our collective historical knowledge, we read the picture as part of this machinery of destruction. But we don’t know whether it really is. And of course, in the context in which the image is placed by Michael the motif becomes charged, opening up to all kinds of interpretations.

JC

In this picture I managed to decipher two of the text fragments. One is “Müllverbrennungsofen” (waste incinerator). The other text says“Müllverbrennungsraum” (waste-incineration chamber). I haven’t been able to find anything else, yet.

TW

As with many images, this leaves us on thin ice, if you will. We can only guess. I would say that this uncertainty is part of the concept of this work. When interpreting the work you can’t find stable ground under your feet. I find this phenomenon of different possibilities of attribution interesting because you don’t expect that in the field of documentary photography. Instead, it turns everything that you from documentary photography upside down. Comprehensibility is missing, connections are not provided, and clear insights are made impossible. In other words, instead completely subjective interpretations are fuelled.

There is a motif in the book that we know as a photograph of the clothing left behind by concentration camp inmates. Schmidt’s close cropping makes it very abstract, almost indecipherable. But when you take a longer look the terrible trace become obvious, because at least for my generation the visual DNA of this motif has been burned into us.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Ein-heit, 1996, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

In another image, the perhaps unambiguous content of the initial is again reduced so much and thus charged up by Schmidt that one must involuntarily think of the scene of an execution or a summary court martial. But it is probably not that at all. That’s what’s so strong in this work. The potential of a subjective interpretation based on a collective memory is triggered.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Ein-heit, 1996, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

I think that a different cultural group reads things quite differently and may not even understand the references. That was the criticism voiced by some people when the group of works was shown at MoMA in New York. The question arose whether their audience would be able to follow the work at all? I think they would. Ein-heit has two sides. It is specifically German. At the same time, it is universally valid because it deals with different social systems, their power structures, representatives, visible signs, even propaganda. During that process, it raises the question of perpetrators and victims.

JC

Is there a collection of the source materials at the Michael Schmidt Archive?

TW

We can trace certain sources quite accurately. There are some books where we can see that he used them. Maybe a dozen. One publication is an anniversary book of the SED, the state party of the GDR. He photographed quite a lot from that book. But there is no huge library or a huge amount of original materials that he used. I was surprised how few there are.

JC

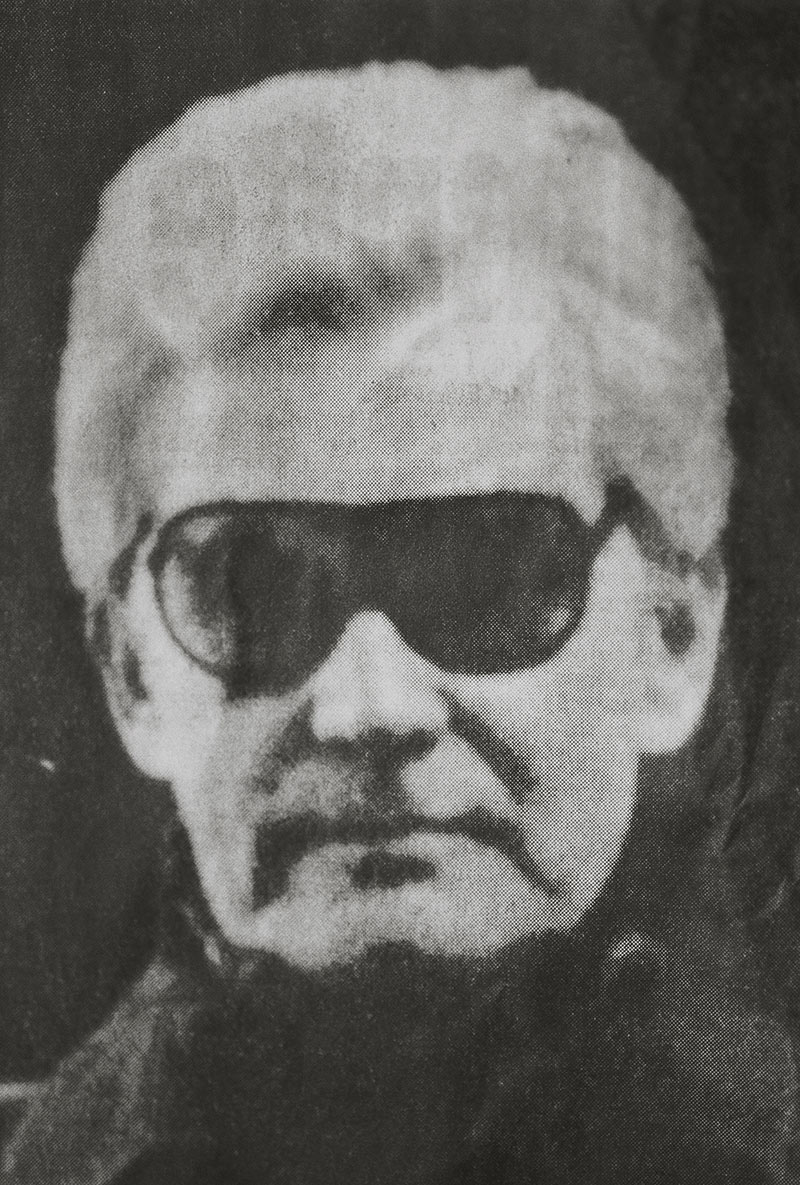

I know many of the people in the photos. I know who they are. But there are some pictures where I think I know them. But then it turns out to be someone completely different.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Ein-heit, 1996, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

TW

[laughs] Exactly! There are also some people from his circle of friends in the book, Wilmar König [shown above] or Joachim Brohm, for example. Schmidt himself also appears with the portrait from his ID. And there are portraits of people from the circle of his daughter from his first marriage, who at the time was active in the subculture of West Berlin. In the photographs of photographs, there are politicians like Lübke, Adenauer or Mielke. But I can’t identify all of them, either. In that case, I read them as types, as representatives.

I’ll show you a portrait where everyone thinks they know. Here. Do you know him from back in the day?

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Ein-heit, 1996, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

JC

I thought that was Heino.

TW

No. I think that’s Wilhelm Wieben, who for many years was news anchor at Erstes Deutsches Fernsehen. But I’m not 100% sure, either. [laughs]

JC

I was thinking about that. On the one hand, it’s interesting for find all the references.

TW

Yes, of course.

JC

On the other hand, there is the risk that the impact of the work will be limited because it may become too specific. It might not be so important to know exactly every person in every pictures. The real topic is the underlying mood.

TW

Yes, I also believe that the quality of the work is formed by its vagueness, by it being unfinished and open ended. Sometimes, you lose this magic when you commit too deep to an interpretation or research.

JC

My research into the details is about finding out more about Michael and his intentions.

TW

Maybe I can tell you a bit about the reception of the project and why it was first exhibited in New York. Around 1987, Michael met Peter Galassi, who at the time was still curator at MoMA’s photography department under John Szarkowski. He had sent him Waffenruhe on the recommendation of Lewis Baltz. There is a response letter, which we showed at the retrospective, in which Galassi thanks him for sending the book. In 1988, Michael was part of New Photography 4 at MoMA, in which he was represented with Waffenruhe. In preparation for the exhibition, Galassi visited him in Berlin. I translated for Michael, who didn’t speak English very well. After the meeting, there was regular contact between the two of them and me.

In the mid-90s, Michael showed him a dummy of Ein-heit. Galassi then expressed his interest to the Siemens Kulturprogramm. He said that he would like to exhibit this project. At the time, that was important for me because the Kulturprogramm had financed the creation of this project without what would come out of it. Galassi’s interest and the announcement that the project would have its premiere at MoMA was very reassuring, not only for Michael and the cultural programme, but also for me.

It quickly became clear that the exhibition would then also be shown at the Sprengel Museum Hannover, where starting in 1992 I was curator of photography. For the presentation in New York, Galassi generously listed me as co-curator. But he did the work all by himself, together with Michael. At his request, the light in the exhibition galleries was very bright. At the pre-opening, a few fuses blew, which was quite funny. [laughs]

JC

Michael created the concept for the book on his own?

TW

Entirely on his own. My function was more like being a sparring partner when you do boxing. He showed me the work or later the dummy again and again and was eager to see my reaction. Often, I had to form an opinion first. Therefore, couldn’t tell him so much at the particular moment. I was only able to do so later. But it was still important for him to have a regular exchange. Of course, I was curious to see what would emerge.

JC

Did he communicate what he wanted to achieve with the work and what his ideas were? Or did he show the work, saying “Have a look. What do you think about this?”

TW

He told me the basic idea of the project. But it changed over the course of the work on his photographs. As did the title. Initially the working title was Daheim. Of course, the term Heimat was being discussed in Germany at the time, because it had been contaminated by the Nazis. Turning back to Heimat — that was already considered problematic.

JC

I’m interested in the fact that the book is very political. What were Michael’s opinions, what was his politics? Do you know something about that?

TW

Michael was a political person. Looking back on his service in the West Berlin police force, he always made the point that he had been on the right side of history. It was consistent for him to resign from the police force at the beginning of the 1970s. He must have been suffering there. After all, he was in the police during the student movement and at the beginning of the RAF. Furthermore, there was his longing to be able to concentrate exclusively on photography. All of this led to the end of his work in the police force. He didn’t talk much with me about those things. When someone mentioned that he used to be a policeman, he was always annoyed by it.

Michael Schmidt, Untitled, Ein-heit, 1996, © Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

JC

I thought that maybe he’d talk about it in private or as an artist.

TW

Not really. He taught himself to talk very precisely about his work. In the beginning, he was unable to do that. He grew up in very modest circumstances and taught himself everything. I always admired his self-education. Apart from a few lectures, there is very little written material from him. Even from conversations I can’t remember any fundamental political standpoints except for emotional expressions.

JC

I was interested in his general attitude towards the subject, the fall of the Wall, reunification. At the time, that was a hot topic. I remember that many people in the SPD said that reunification was not an immediate possibility and that we had to wait and deal with history.

TW

Right.

JC

That didn’t work out. History simply developed more quickly. The conservatives wanted reunification right away. I was curious what he thought about that. Everyone had an opinion.

TW

I would say that he had the hope that there would be a third way, which we as the left had hoped for at the time, namely that one would take the best from the two social systems and try to create something new.

But I also realise that I can’t really answer your question. We did talk regularly and often on the phone over a long period of our friendship. But it was a lot about getting each other’s daily problems off our chests.

JC

In the end, this leaves us with possibly the best solution, the work itself.

TW

For sure. It’s quite hefty and really hard to grasp. Ein-heit is not a book that you can understand quickly. As a viewer, you are initially thrown back on yourself. Usually, photographs open up relatively quickly. In certain contexts in which they are used they have to be quickly readable. Otherwise they would not be successful — I’m thinking of advertising or photojournalism. With Ein-heit it’s just the opposite. Since I first looked at the book, it has become more and more complex for me. Questions always remain. Of course, that is interesting. I only know the same feeling from very few other photography books, for example William Eggleston’s Guide or Walker Evans’ American Photographs.

In Ein-heit it is also remarkable how many interpretations a picture can allow. There are many more of those than there are pictures in the book. Often the content does not arise in individual images but only through the sequence of images in the book. Sometimes it arises between them. Michael Schmidt reduced this idea to the simple formula 1+1=3.

JC

A younger generation certainly will see the images differently now, because they may not even know all the references.

TW

Yes, I agree. If you take collective memory as the basis for understanding something like this work, then it’s always generational and limited to a culture. Americans will read the book differently. Someone who now is 20 years old also sees it differently. They might see certain types in the portraits, but they don’t recognise the people. They don’t make any rediscoveries.

JC

Perhaps there will be discoveries that are denied to us.

TW

That would be great. Then the book would remain timely, and it would not just be a work with a historical reference. That would be ideal.