“Most people are nothing,” Fran Lebowitz told Helen Molesworth in a short clip on Instagram that I came across today, “by which I mean they’re of no consequence to anyone but themselves.” If you wanted to, you could see these words as the impetus behind making art: to create something that is of consequence to other people, even if you might not know who these people will be or, for that matter, whether there actually will be such people.

But the above also is the viewpoint of those who can have such conversations in a million-dollar art space or those, like me, who have some sort of relationship with them, however imagined and/or tenuous and certainly inconsequential it might be.

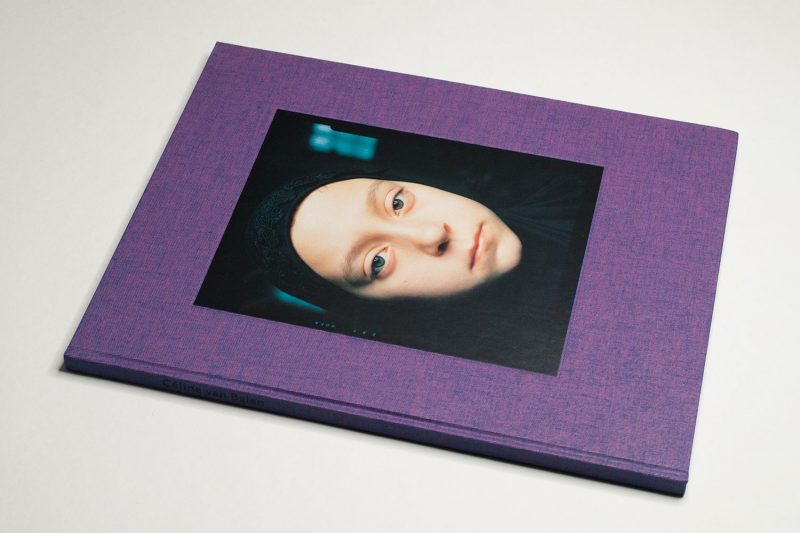

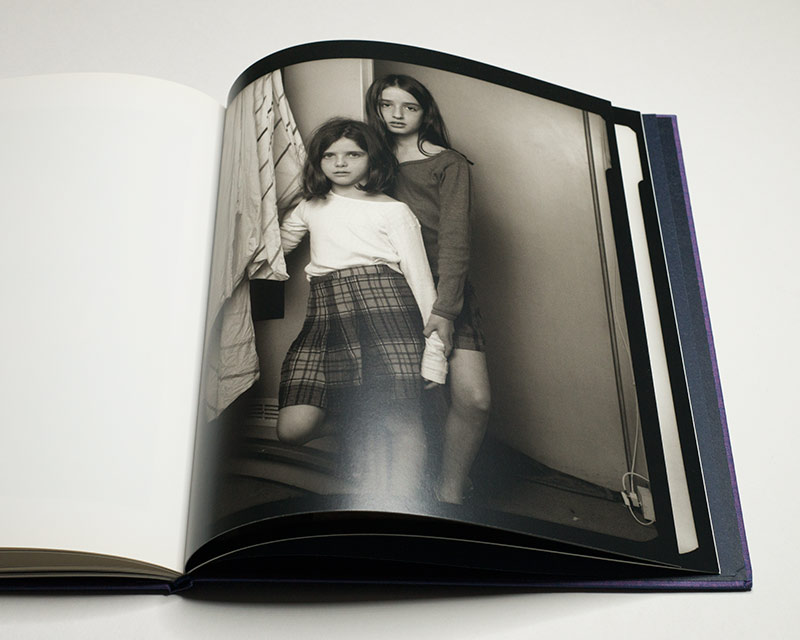

There is another viewpoint, expressed by Remco Campert in the foreword of Céline van Balen, a book that accompanied a large exhibition of the photographer’s work in 2002. “We go unnoticed,” he wrote, “because that is better for everyone. We are of no further use. The rest of the world has pushed us aside, untouchable. By not seeing us, they mean to deny us. But we live on.” (You can read the full text on the publisher’s website.)

Campert wrote these words about the people in Van Balen’s portraits. Just a little bit later, the photographer would join them. “She retired from photography in 2004,” Kees Keijer wrote in an article published on 28 July this year, “after finding it increasingly difficult to cope with the pressures of producing, exhibiting and performing. Her mind was ill-tempered with the success and the vague promises and high expectations that accompanied it. She struggled with a drug addiction that slowly crumbled her social life.”

(Please note that wherever the text is in English but a link goes to a Dutch language text I’m relying on machine translation. I corrected minor translation errors where needed.)

“Céline van Balen died of cancer on April 1,” we also learn, “and was cremated on April 8 at De Nieuwe Ooster. The fact that the news has only now become known is indicative of the way in which Van Balen had turned her back on the art world.”

“The city asks nothing of us,” Campert wrote, “the city is indifferent. The city is our best enemy.”

The art world asks nothing of us. The art world is indifferent. The art world is our best enemy.

If you have ever seen the photographs made by Van Balen, you will probably find it hard to believe that they’re not more well known outside of the Netherlands. Then again, if you know anything about the art world that the photographer decided to leave, you will not find it hard to understand why that is not the case.

After I heard of her death, I did a quick Google search and found an assortment of links to auction houses — money is still being made with her work, money she would never see because of the way the art world operates. There was one link that shows one of Van Balen’s iconic photographs with a short, yet insightful text about the work. If there are others, I didn’t see them.

Most people are nothing, we might add to Lebowitz’s words, not because they create “no consequences to anyone but themselves”. It’s because it takes two for those consequences to arise, in particular the people who decide to pay attention.

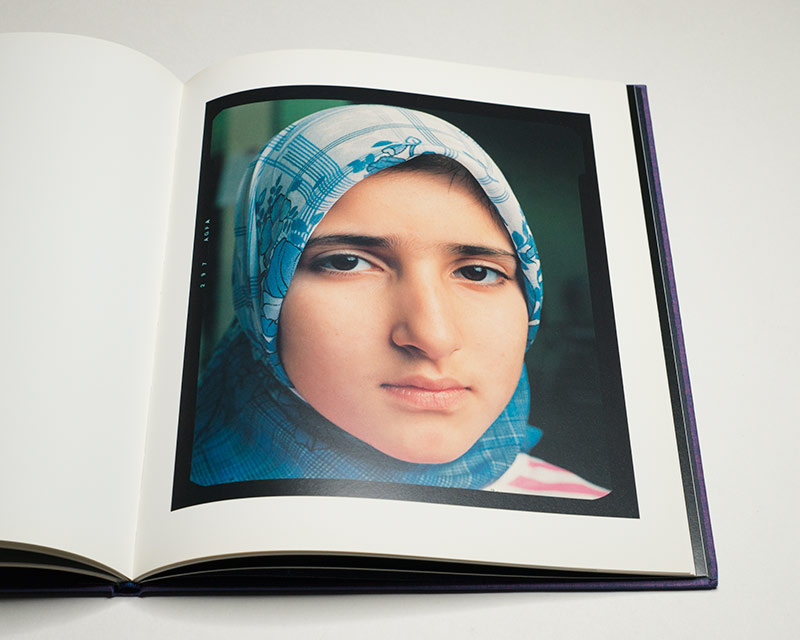

This is not merely an art-world problem (even though in an obvious sense, it is very pronounced there). Collectively, we have decided to treat large numbers of people as nothings, whether they’re not well-off people or migrants or refugees or chronically sick people… The list goes on and on.

As Van Balen demonstrated, it doesn’t take much to break that mechanism. In her photographs, she consistently placed people in front of her camera that art-world denizens would probably view as nothings.

How the art world is incapable of seeing its own massive contradiction — being an insular society of mostly wealthy people that betray a shocking disregard for those less fortunate, while ogling photographs of the very people considered as nothings — escapes me.

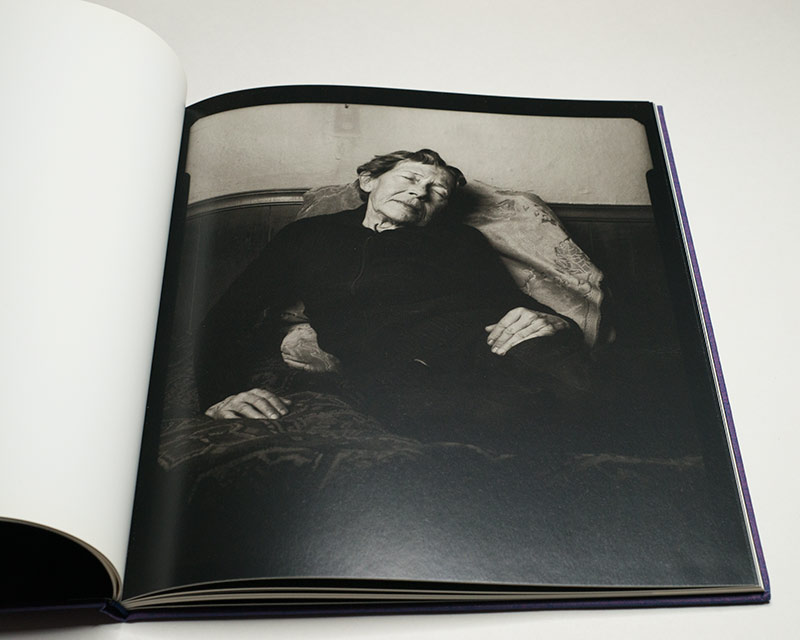

The art world loves nothing more than looking at photographs of underprivileged people, ideally male drifters with long beards or middle-aged women whose faces document the many hardships they have already gone through. Scores of photographers have built their careers on this. It’s not even that poverty is picturesque. It’s simply that poverty creates the preconditions for good pictures for them.

But less fortunate circumstances can also produce photographs that ennoble — rather than expose. Céline van Balen is filled with such photographs. I suspect that even the fans of Richard Avedon’s poverty porn from the American West might admire Van Balen’s tender portraits.

In the end, the reason why these photographs are different than Avedon’s mighty simply be because Van Balen cared for the people in front of her camera — and Avedon did not. We can’t know that for a fact; but we can see it in the pictures. “When you’re taking photos,” Kazuo Kitai recalled advice he received from Ihei Kimura, “put yourself in the position of the weakest.” Van Balen would’ve understood. Avedon? Not so much.

What the exact reasons might have been for Van Balen’s retirement from photography (if we want to call it that) I have no way of knowing. I’m thinking, and this is just a wild guess, that the photographer also saw through the way photographs — and by extension those in them — were and are treated and considered in the world of art. I’d like to think that she was going to have none of that.

What’s left is the book, and there are photographs in some collections. Part of the photographer’s archive has gone to the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam, where it will be in very good hands.

“The work goes on,” Ted Kennedy ended a speech from a completely context (but I might as well use his words here), “the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die” — the dream that we’ll stop thinking of people as nothings. Whether or not the art world will come along, though… Let’s not get our hopes up on that.

RIP Céline van Balen