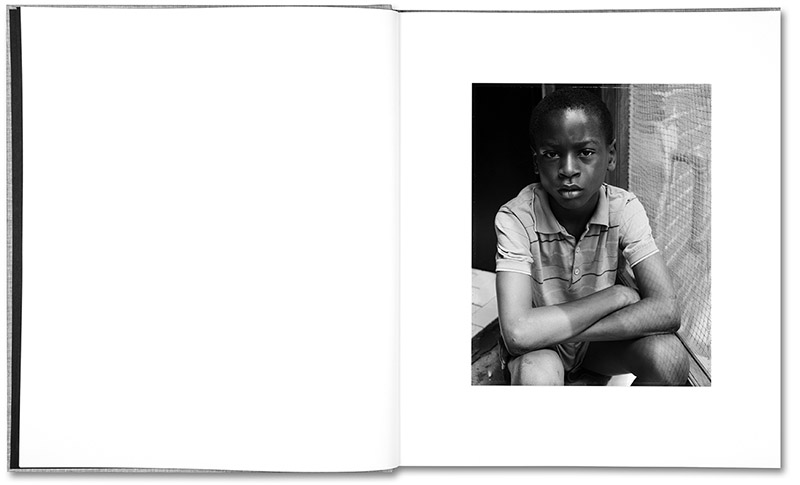

I’m looking at the picture of a young boy. He is sitting on what might be the front step of a house: to his left, there’s a screen door that he’s holding open with his knee. The young boy’s arms are crossed, resting on his knees. Maybe it’s the pressure from the screen door that has him slightly tense, maybe it’s the fact that there’s a stranger with a camera in front of him, to take his picture. There’s defiance in his look, the kind of defiance that boys his age often share: they’ve discovered the fact that they’re their own people in this world, a world that they need to push against. Eventually, they will be men, and as a young boy you become very conscious of the role of men and the way they appear to have to act.

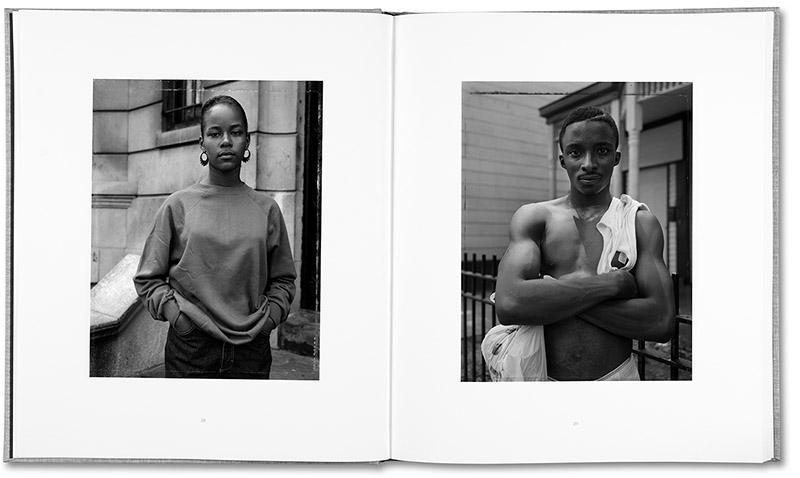

I’m looking at the picture of a young women. I am slightly undecided whether I should call her a girl or a young woman because I can’t tell her age. But there’s enough for me in the picture to decide that “girl” is the wrong word. Much like the boy, she is physically constrained by her environment. At first, I thought it was another door. But now I see that she is leaning against the frame of a shop window (given what I can see, it looks like a deli to me). Much like the boy, she meets my gaze (or rather the camera’s, but of course I’m bypassing that detail) while holding her right arm in front of her, pressing it against the shop window’s timber frame. I can’t help but see a slight hesitancy in the way she looks at the camera: she knows something that I will never know.

As I’m making my way through Dawoud Bey‘s Street Portraits, I’m looking at a lot of boys and girls, young women and men, older women and men. Almost all of them look back at me, which has me curious about them and their life experiences. Some smile, many more are serious. A lot of them must have thought about how they wanted to present themselves to the photographer’s camera, while others look like they were just happy to be in the picture. Where all-too-often, art photography falls on the serious side — people tend not to smile, here the pictures are not that. They’re serious, but I’m sensing that the photographer was more interested in his subjects being themselves than in shaping them for his pictures.

I couldn’t take these pictures. To begin with, I’m usually too timid to ask strangers whether I might photograph them. But I’m also someone different in more ways than one. All the portraits in Street Portraits show African American people, and I’m a white German guy. There’s more than one world between the people in the pictures and me. There’s the world that’s between me and any person who was born and grew up in this country (I’m an immigrant; legal lingo: resident alien). And there’s everything that over the course of the past few years has been brought to the forefront by writers such as Ibram X. Kendi or Ta-Nehisi Coates. I am, to use Michael Rothberg‘s term, an implicated subject — like many people in more ways than just one.

The camera is a terrifying tool. Simply by pressing its shutter button when taking a picture of another person, a photographer will place her or his subject somewhere on the spectrum that has the Other at one extreme end and whatever the complete opposite of the Other is at the other. It’s tempting to think that this is a big problem only for photographers. But as Maggie Nelson makes clear in The Art of Cruelty, it’s too easy for an audience to place the onus only on the maker. “As Susan Sontag has justly observed […],” she writes, “focusing on the question of whether or not an image retains the capacity to produce a strong emotion sidesteps the problem that having a strong emotion is not the same as taking an action.”

Over the past few years especially, as I’ve seen a great many discussions about photographs play out on social media (obviously not the greatest environment for such discourse: you can and usually will have strong emotions, but what or where are the actions?), I’ve ventured more and more into the territory explored by Nelson when approaching photography in general (not just when dealing with what I perceive as cruelty). Photography is a great tool to work with if you want to engage with the world as an implicated subject: its visual immediacy can force you to strongly challenge your beliefs (even if occasionally you end up confirming them later). If the act of photographing can make a person vulnerable (because they’re in front of a camera), the same is true for the act of looking at photographs (albeit in different ways).

It is the sheer humanity on display in Bey’s Street Portraits that has had a profound effect on me. I remember feeling the same way when, for example, first encountering Ernest Withers’ photographs from the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike that would later be echoed by some of the imagery coming out of the Black Lives Matter movement. Even without a person holding a sign that says “I am a man” (as in the 1968 strike) or “I am a woman”, “I am a human being”, photography can remind us of the fact that by depicting a person’s face and body in a picture we, as viewers, are facing another human being whom we might be indebted to in however indirect a fashion.

After all these years of looking at pictures, of making them, of teaching others to look at them or make them, I still couldn’t say with certainty why people fall where they fall on that spectrum that I spoke of earlier. I have a good idea what you have to do to other people. But how to avoid that, or rather what to do to avoid it — it’s not clear cut. Good intentions, for example, help, but they don’t guarantee anything.

Maybe, and this is the possibly most useless explanation I could offer, it’s the feeling of a shared humanity beyond the very broad one that we all have in common. There will have to be something that has the photographer connect very deeply with the people s/he is photographing. The quote by Maggie Nelson continues as follows: “‘You do not necessarily feel [compassion],’ Buddhist teacher Chögyam Trungpa once warned a student who was worrying about how to act compassionately without feeling it first. ‘You are it.'” I’m not a Buddhist, but this makes perfect sense to me.

This is the essence of what I see in Dawoud Bey’s photographs, and it is what the photographer shares with all of us. We ought to be very grateful for that.

Recommended.

Street Portraits; photographs by Dawoud Bey; essay by Greg Tate; 120 pages; MACK; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article about photobooks, you might enjoy my Patreon: longer, in-depth essays about books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.