“The object of our mind can be a mountain, a rose, the full moon, or the person standing in front of us. We believe these things exist outside of us as separate entities, but these objects of our perception are us. This includes our feeling.” I had to think of these words by Thich Nhat Hanh while spending time with Petra Noordkamp‘s Better Not Move, a book of photographs and text that is an expression of grief.

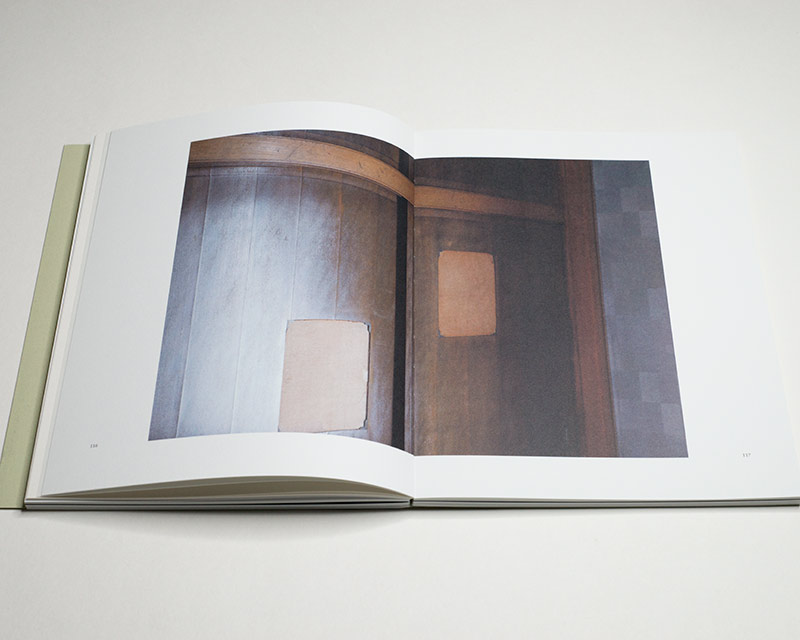

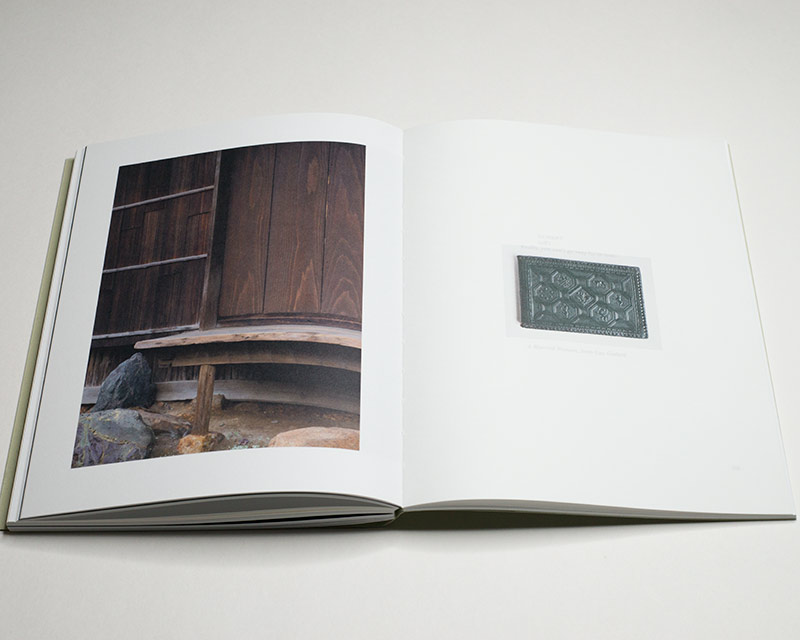

The bulk of the photographs in the book were made during a residency in Japan shortly after the artist’s partner had died unexpectedly. They are photographs of the ground, of the roots of trees, of rocks, of the insides of traditional Japanese houses. In addition, there are a few photographs of personal items that have nothing to do with those. These pictures come before short pieces of text that are sourced from a number of movie screenplays (none of which, I admit, I was familiar with).

The short texts focus on men and women as partners in relationships — marriage and the like. Noordkamp added a couple of longer texts of her own, one obliquely describing her time in Japan during the residency (there is a fear of earthquakes), the other outlining the larger situation: there had been the man who had died, and the three months in Tokyo were spent dealing with that fact. “Photographing the lines, structures, shapes and patterns,” she writes, “gave me something to cling onto and offered comfort.”

Ever since a number of artists photographed the possessions of people who had died — Christian Boltanski might have been the most prominent example — photographers have been focusing on treating such pictures as traces of their presence. In fact, one of the most common projects for photography students centers on taking pictures of typically a grandmother’s or grandfather’s possessions.

Interestingly, Boltanski never believed that his Inventories said anything about the person who had been in their possession: “Their only interest is that anyone who looks at them sees his or her own portrait in them, since we all own pretty much the same objects […] We learn more about ourselves than about the person behind the inventory.” Had Thich Nhat Hanh been a photography critic, he would have easily agreed with this. But he didn’t have to play that role, because his Buddhist teachings make the point very clear: the objects of our photographs, to adapt his words to this context, “are us”.

“Do not lose yourself in the past,” Thich Nhat Hanh continued a little bit further down in his essay on Right Mindfulness (in: The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching), “Do not lose yourself in the future. Do not get caught in your anger, worries, or fears. Come back to the present moment, and touch life deeply.”

In the end, all photography is a combination of paying attention to something and trying to have other people partake in that: the attention itself and not so much whatever it is that is its object. Different types of photography do this differently. In a simplified fashion, we could say that the world of art photography is mostly centered on the former, while the much vaster world of social-media photography focuses on the latter (hence the often absurd admonishments produced by photography critics attempting to deal with how ordinary people take and use pictures).

The problem, of course, is that looking at photographs as — for a lack of a better word — documents is a lot easier than to view them as relatively unimportant aspects of a social gesture. You can write a detailed critique of what a photograph looks like, how it was made, or how you engage with this aspect. But it’s a lot harder — and yet a whole lot more rewarding — to try to understand other people’s pictures as part of their attempt to navigate their place in this world.

As much as I typically try to be aware of the different ways photographs can operate, when looking at art books, I always start out with focusing on what is being shown. As it turned out, this made my job when dealing with Better Not Move harder. After a while, though, I started focusing less on the photographs and more on the person who had made them. I started to imagine myself in her place, looking intently at what is on view.

Operating a camera can and usually will divert our attention away from what we see through the viewfinder to how we see it that way. As photographers, after all, we are craftspeople who are worried about our pictures’ form and content. As viewers, though, we don’t necessarily have that problem. The pictures have been made, and we can access them in ways similar to how Noordkamp accessed the stones or roots or walls, as the objects of our perception that Thich Nhat Hanh spoke of.

I have no way of knowing whether thinking about photography this way will be helpful for a world of photography that still is so focused on ideas such as indexicality. Still, art always is about its makers and about the connections we, as viewers, can establish with them. I see Better Not Move as a meditation on what it means to still be there while someone else is not, with each photograph being its own small assertion of that fact.

The more I looked at the book, the more I ended up focusing on the moments in which I did that. My looking became my being.

This idea led me to deeply appreciating this book, which, I should add, has been beautifully produced with just the right amount of careful attention to detail.

Recommended.

Better Not Move; photographs and texts by Petra Noordkamp, with text fragments from a number of movie screenplays; 192 pages; Architectura & Natura; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!