Photography is often used to communicate the essence of a community, the feeling of what it might be like to be immersed in it. For very good reasons, a lot of discussions have centered on this very idea. Can an outsider, someone who was and is no member of the community, arrive at what an insider, someone from the community, will be able to see? In all likelihood, the answer is no.

In the very worst cases, which more often than not can be found in photojournalism, helicoptering in an outsider will at best paint a surface picture and at worst perpetuate harmful stereotypes. This is not to say that an outsider by definition will be unable to arrive at a deeper truth of the community. But to get there, a lot of careful work will have to be done. A recent example of how this can be done masterfully would be provided by Anders Edström’s Shiotani.

Given that photography is a visual medium, the feeling of community has to be communicated visually. Unless there is added text, the sense of community has to come across through the combination of photographs: in essence, a viewer has to be able to feel that they are in the presence of a community, even as they might be experiencing things far, far away and mediated through the artifice that is the photobook.

Colby Deal‘s Beautiful, Still. provides a very good recent example of a portrait of a community made from the inside. In its second picture, which comes right after a short poem by Hakeem Furious, two Black women in bright white clothing are depicted standing in what looks like the backyard of a house. They are turned away from the camera, and the taller woman is holding the other one in a caring embrace. It’s a photograph of intimacy and care, and it sets the tone for much of what is to come in the book.

The next few pictures sketch out more of the larger environment, an environment that depicts a genericness that is very distinctly a feature of the United States, even as there are variations based on class and regions. As someone living in the Northeast, the book transports me to a locale somewhere further south.

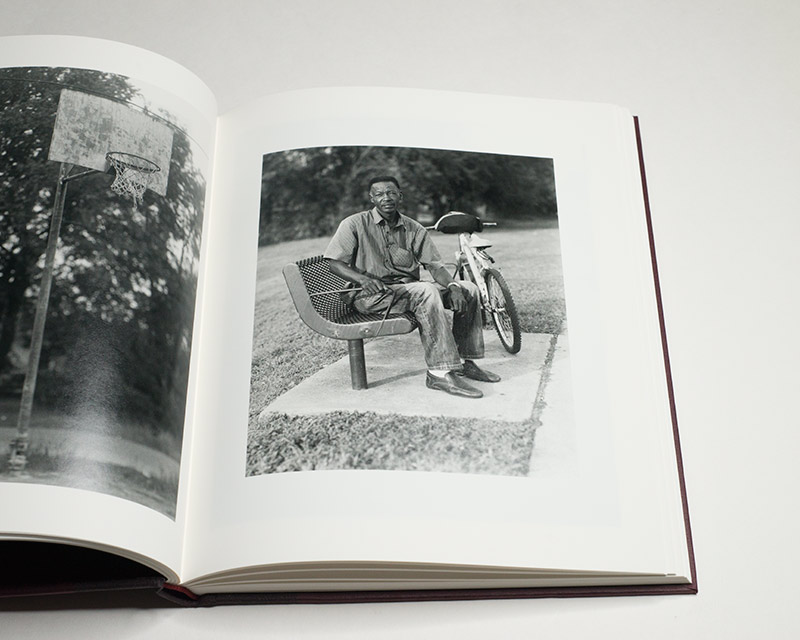

While there are people in some of the first pictures, it is the first photograph that gives unconditional attention to a young woman that jolts the viewer, letting them know that this is a book about people forming a community rather than a description of place. The photograph shows a young woman in a white, laced dress. She’s holding her hands folded in front of herself. Her gaze is directed at the camera, projecting a combination of calmness and confidence.

A number of photographs of other people follow, a mix of more formal portraits and pictures taken while life was going on. From there on, the book develops the themes thus introduced, fleshing out life in a Black community (in the Third Ward in Houston, Texas).

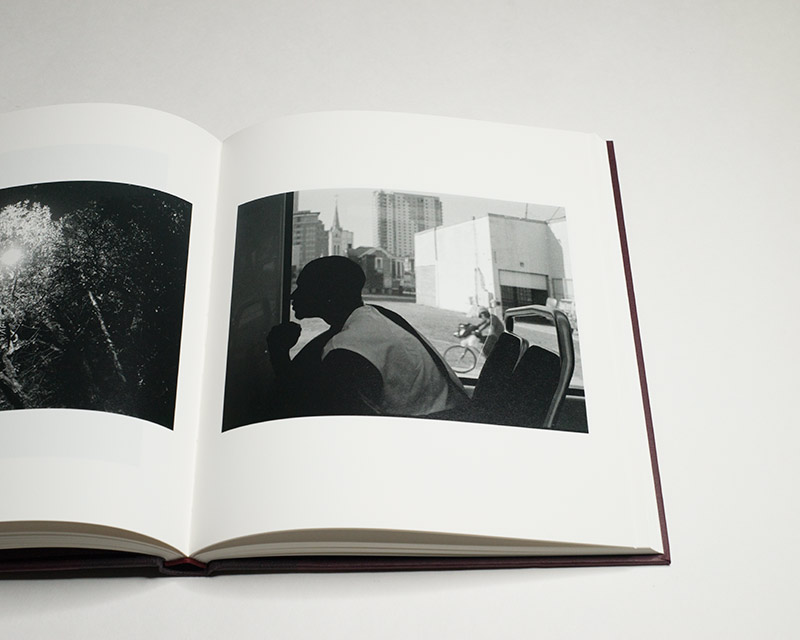

For the work, a number of different cameras appear to have been used, resulting in differences in formats, with square photographs and rectangular ones being present. Different tools allow for approaches catered to different situations, enabling the photographer to mix a formal setup with a more fluid approach. This is very effective.

However, I am not sold on the inclusion of so many photographs that are technically imperfect in the book. This is not to say that I’m oppose to imperfect pictures in general. But in the context of the book, they have to work in support of the book’s overall message. A good example for that is provided by Sabelo Mlangeni‘s Isivumelwano where the use of technical imperfections is deliberate in a Brechtian sense.

Here the imperfections feel photographic only — which would be fine if the book centered on what photography is or can do. Alas, that’s not the focus of the book. As a result, the imperfections feel like too simple a device for an otherwise very sophisticated and visually beautiful body of work. In general, technical choices should not be allowed to focus the attention on themselves — instead of on the larger ideas.

The end result of this all is an impressive debut monograph by a photographer whose voice is now added to the growing canon of American photography. We ought to pay careful attention to Colby Deal, in particular given his ability to both convey what being a member of a particular community means and to have outside viewers partake in it visually.

Beautiful, Still. contains all the beauty that will forever be elusive to photographers that helicopter into some community, regardless of whether they want to “bear witness” or “paint a portrait”.

To take good pictures means to be able to feel a moment shared with others. That, and only that, is what can make photography art.

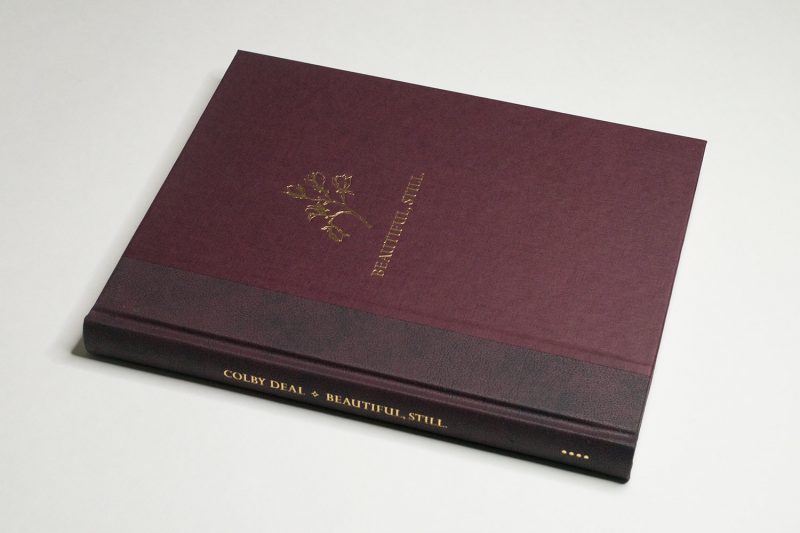

Beautiful, Still.; photographys by Colby Deal; poem by Hakeem Furious; essay by Garry Reece; 160 pages; MACK; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!