In photography, all too often the tristesse of contemporary life is given an expression through equally sour photographs that often are devoid of a direct human presence. I can see the appeal of such photography — for a while, I was drawn to it myself. Might one not describe vast parts of the so-called Düsseldorf School as operating along those lines? Even where there literally are thousands of people in the photographs of Andreas Gursky, the effect is the opposite: it’s as if nobody is there.

I can see the point of such work, but I now view it as one of those many dead ends that the history of photography is filled with, where a photographic approach first turns into style and then into mannerism. Lest you now send me emails with your latest “street photography” – that’s not much better, merely exchanging one mannerism for another, the differences in styles notwithstanding.

Maybe that’s the struggle every photographer has to face: how to arrive at something without having that — whatever it is — exhaust itself as an ultimately empty formula. For a variety of reasons, that’s difficult, because who is happy to abandon what might have been so hard to reach? And who wants to tell their gallerists and/or publishers that more of the same just doesn’t cut it for anything other than paying the bills?

I’ve been itching more and more to see a human presence in photographs, ideally one where I can feel a real connection between the person in front of the camera and the one behind. And when I use the term “real connection” I’m explicitly excluding the macho approach to photography, which, sadly, is still all-too common (older male goes out into the world and sticks his camera plus flash into the faces of the most vulnerable — you know what I’m talking about).

I suppose what this all comes down to is that I want to look at photographs where I can sense that their maker cared about more than their own ego. Obviously, all art is rooted in the artist’s ego; but it doesn’t have to stop there. As an artist, one can — I’d say: one should — move beyond one’s own ego.

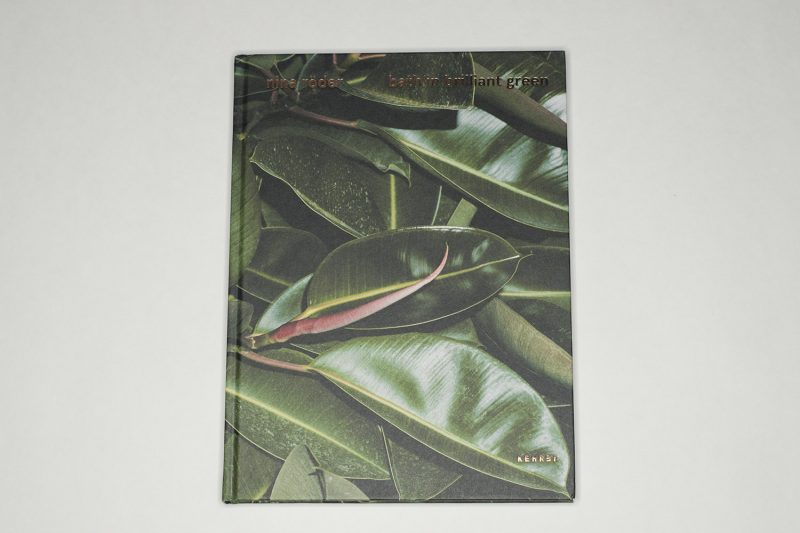

The above might read like a strange introduction to Nina Röder‘s Bath in Brilliant Green. But it is what I arrived at, thinking about what was going on the background of the work. There are, after all, plenty of photographs in the book that look like some form of collaboration between a person and the photographer. People are shown engaging with part of the land, often in the nude, or they are seen adorned with materials that stand in stark contrast to the softness of their flesh.

It is that very softness, and its rosiness, that hint at the vulnerability of the human condition that rests at the center of the work. The world is depicted as being what it is, harsh and unforgiving, and we humans have to deal with that, whether literally or figuratively.

I sense loneliness and longing in these photographs. To what extent that read is based on what I bring to these pictures I couldn’t say. In the photographs, the figures are always on their own, and for the most part their faces are being hidden or turned away. They are, in other words, nobodies. But they’re not nobodies in a social sense, they are nobodies as human beings in an environment that is hostile to them being there. This fact points at why we collectively ought to take better care of each other: there is nothing else in this world that could do that for us.

Bath in Brilliant Green mixes landscapes with still lifes with studio photographs and more, and it does that well. For sure, there is that clear thread of feeling going through the work that I spoke of above. It’s edited and designed well. However, for my taste, the book’s printing falls on the lifeless side, with shadow detail sorely lacking. This means that images dominated by dark tones lose a lot of definition, at times resulting in muddy flatness. I think that’s unfortunate.

But all in all, it is the human presence in the work that carries most of its meaning. Working with people in front of the camera is hard. It requires work, dedication, passion, empathy. And obviously the performative style of photography used in the book isn’t the only way to do it. Still, what a difference it makes to see human figures — and not just landscapes devoid of a human presence!

Bath in Brilliant Green; photographs by Nina Röder; texts by Sarah Frost, Nicolas Oxen; 144 pages; Kehrer; 2018

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 2 – Overall 3.1

Ratings explained here.