It was roughly halfway through a conversation with Polish photographer Rafał Milach when I realised that my original premise for this piece was misguided. But let’s start at the very beginning.

Poland’s ruling neofascist party, PiS, understands that for it to destroy the country’s democracy and cement its power it needs to undermine the judiciary. Finding majorities for its far-right agenda is sometimes difficult, especially since the courts might stand in the way of implementing measures that violate the constitution. Thus, a few years ago PiS set out to “reform” the courts. “Reform” here means stuffing them with lawyers who aren’t interested in the law but who instead do what they’re supposed to do (this might sound very familiar to Americans).

A huge fight erupted with the European Union (EU). The rule of the law is the main basis of the EU, and the EU would have none of PiS’ judicial manoeuvres in Poland. But the EU was powerless to prevent Poland’s “reformed” highest court from declaring that abortion was illegal (again, this might sound very familiar to Americans). In late 2020, Polish women thus became second-class citizens.

All over the country, huge demonstrations erupted. There had already been large demonstrations against the judicial “reforms”. But the abortion ruling triggered the largest wave of demonstrations since the fall of Communism. A large group of photographers joined in and took pictures of what was happening in their communities. This is where the situations in Poland and the US diverge.

The Polish photographers decided that their separate work needed to come together and live in a shared space: the Archive of Public Protests (APP). In addition, the work would be shared not only online but also in physical form, as a mass-produced newsprint publication that was going to be handed out at demonstrations: the Strike newspaper was born.

There quickly was a succession of these publications as the political situation in Poland spiralled out of control while a number of other crises popped up. There were additional Strike issues about climate protests and the migrant crisis at the border with Belarus. After the war in Ukraine started and a huge wave of refugees arrived in Poland, there was a newspaper about that as well.

As you might remember from a number of articles on this site, I have been extremely interested in APP and the Strike newspaper. I don’t believe in the idea that photographers should set themselves apart from the societies they live in. I also don’t think that it’s a good idea that photographers are only making work for their peers and a small select group of curators (typically trained in art history or curatorial studies, whatever the latter might be) and wealthy collectors.

Karolina Gembara handing out Strike newspapers in Warsaw

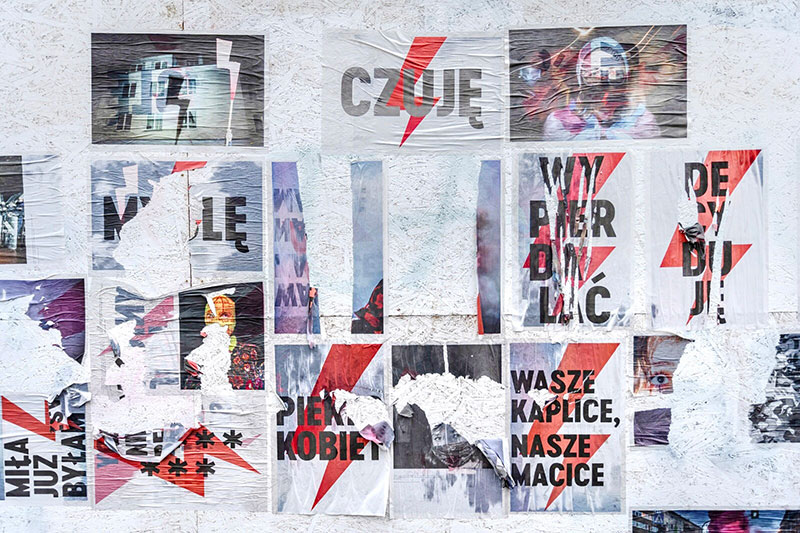

The Strike newspapers made these Polish photographers active participants in the protests. Not only did they share their photographs for free, they also incorporated slogans from the protests. Someone picking up a newspaper might use it at a protest or maybe hang it in their window for other people to see.

Now that about three years had passed, I was curious about how things had evolved. I decided to approach two of the members of APP that I know well, Rafał Milach and Karolina Gembara (I spoke with them separately).

Specifically, I thought, it would be great to learn about the impact of these newspapers. And that’s where I had it all wrong. Or rather I realised that while seemingly rejecting standard photoland thinking — where the impact of something is measured by how many copies it sells and by how much of a commotion it triggered, I had internalised that very thinking after all.

“We never had a plan,” Rafał tells me, “we were aiming for one edition of the first issue. I was receiving so many good images. I knew that they’re going to disappear, even if we put them in the Archive. It’s possible to find them, but it’s difficult. So when you have this tight edit of very strong images, that can bring you back to this time and energy around the protests.”

I suppose the lack of a plan cuts both ways. On the one hand, you’re driven by your energy, and you push things a lot faster than if you were to proceed more cautiously. And how could you be cautious if there’s a civic emergency right outside of your kitchen window?

On the other hand, once you roll the boulder down the hill (to use a rather imperfect metaphor), the hill — not you — will decide where it will go. “Recently,” Karolina says, “I participated in a workshop for activists with a focus on the theory of change. This is a theory where you sit down with your colleagues and discuss the change you want to make. There are certain steps and one of them is to establish the goal: what would be the outcome of our activity? And how do you measure it? How do you know that we achieved the goal? I realised that we applied none of this to our work at A-P-P.”

A simple way to measure impact would be to look at the numbers of newspapers produced. Rafał: “It’s certainly above 30,000 [newspaper copies so far]. Maybe more. It’s a lot when we think about the photobook world. It’s even a lot when you think about mainstream print media. Print runs are dropping because everyone is cutting costs. In the Polish market, weekly magazines that used to have 300,000 copies now operate at the level of 50 or 60,000 printed copies. Of course, we have a total of 30000. And I’m not saying that we compete with mainstream media outlets. It’s a relatively small, but relevant number of printed newspapers that can be used in the Polish context.”

“I would say that the newspapers contributed to the visuality of the protests in Poland,” Karolina says, “we see them in windows, in people’s houses, in cars. A lot of people send us pictures of these displays. They use them as a way to communicate — to their neighbours, to the streets, to pedestrians — what they stand for.”

It’s exactly here where my original idea for this piece stopped making sense. Looking at numbers of newspapers, thinking about a direct, measurable impact — this thinking reduces the whole idea to only a narrow utilitarian aspect.

Both Karolina and Rafał were a little stumped when I asked them about the impact their work has had. “The best feedback that we can possibly get,” Rafał tells me, “is that people are sharing images of the newspaper on social media. And we see how the newspapers are used in different locations, how they are reused. Very often, it’s in the background of mainstream TV broadcasts.”

The larger impact is hard to assess, though, as Karolina explains: “Sometimes we would send 100, 200, or 300 copies to a place that requested those newspapers, such as a university or a photography festival. We trust the people, we trust the kinds of events that the newspapers were used for. But their impact is hard to measure. Maybe newspapers got stuck in someone’s basement? Having said that I wish we had more resources, both in terms of people and money, to send it to more places.”

I suppose what this all comes down to is that if your work becomes a part of a civic engagement that explicitly rejects some of the mechanisms from the bubble you operate in, that engagement follows its own, larger societal rules. You drop the big stone into the pond and you allow for the ripples to move outwards — without expecting too much back in return. After all, real civic engagement lives exactly off of that: actions that are the means to an end that exists in a different sphere altogether.

Both Rafał and Karolina made it clear that there were a number of other aspects that in part were unforeseen (possibly in part because they might have been unforeseeable). “Photography has a handicap as a medium when it comes to communication,” Rafał says, “text is so much stronger. All the electricity is about the text, about the language, about the slogans, about something that is very much verbal and non-visual. I’m not saying that the visual representation [of the protests] is not important. But the most electrifying things are connected with the language and with the text. That is something I learned from these publications.”

I think in the world of photography we often think that our pictures will do more than they actually do, in part because we overestimate what they can do. Can a photograph compete with the symbol of the red lightning that’s part of the women’s rights movement in Poland? It would seem that the answer is no.

And there were other insights. “To me making a newspaper is a way of coping mentally with the problem it raises,” Karolina notes, “when the war in Ukraine stared I responded to almost every request: finding transportation, accommodations, hosting, or simply making sandwiches for people arriving at the train station in Warsaw. I was really terrified and exhausted as there was no end to the needs. Then we started making the newspaper, and although it felt less practical, I knew this tool and I knew it worked. Some people are simply far more effective when it comes to psychologically taking care of others.”

Maybe this is the big lesson from the APP newspapers: What matters is that they were made and brought out into the world. Whatever ripple effects might be produced is something difficult to predict — unless, as Karolina noted earlier, you adopt the tools and methodologies of activists.

But there is another aspect: locale. I had long been wondering why the idea of the free newspapers had not been adopted by people outside of Poland. After all, there are plenty of problems in many countries.

As it turns out, for a number of reasons, things might not be as simple as that. “My personal experience with the newspaper devoted to the humanitarian crisis at the Polish-Belarusian border in Berlin was quite upsetting,” Karolina tells me, “I went to some protests because we had published that particular issue also in German. People didn’t want to take it from me. There was an argument around the paper. They didn’t want the waste. But I also felt that there was no trust in what it is: maybe a propaganda? I was trying to explain what the newspaper is about but a very few people actually took one from me.” As a consequence, she says, “it is maybe fair to notice that in Poland the newspapers are known, requested and used. But abroad they get more attention in the institutional context.”

This might also explain why we haven’t seen similar initiatives outside of Poland. The US protests against the abortion ban were much briefer, and there was no equivalent of the Strike newspapers.

I will admit that I had some naive hopes that APP and their newspapers would trigger similar initiatives elsewhere. But this does not appear to have happened, which might say more about different civic cultures and societal differences than about photoland itself. Given that the newspapers are now finding their ways to Western cultural institutions and festivals, there always is the chance that their spark might light a local fire after all.