For the longest time, humans have collected and sorted and organized entities to make sense of the world, whether physical or abstract ones. Not surprisingly, ever since it was invented photography has become an essential part of this endeavour: where pictures themselves aren’t the entities to be collected, sorted, and organized they have been produced to provides visual aids. This has become such an obvious facet of our daily lives that we don’t even realize its presence any longer.

By construction, photobooks are sorted and organized collections of photographs. Given that the purposes of most photobooks extend beyond this basic aspect, we hardly ever notice. And in many cases where that purpose does not extend any further, it usually becomes such an essential part of the work in question that there is no need to question it — or expect more.

For example, nobody in their right mind (well, we’ll come back to this) would expect a photobook by Bernd and Hilla Becher to be anything a very dry collection of monotonously photographed industrial installations. The point is exactly that: through the accumulation of things that look very similar (whether in real life or in photographs) their internal characteristics are exposed, and they are revealed as “anonymous sculptures”.

Of course, someone a little bit less enarmoured with art hierarchies might find the Bechers’ life work to be good but lacking, given that its understanding of the word “sculpture” is rather limited. Those collections do their job and, I’m told, a lot of people do not find them as dreadfully boring as I do. I don’t mean the good boredom, the one that opens the senses; I mean the kind of boredom you experience, say, when you have a long international flight, you barely got any sleep, and there are those 30 minutes to spend before the landing: your senses have become almost fully dulled.

I don’t mean to argue that the Bechers’ life work isn’t art; it’s just that I personally prefer art to take me to a point where I wonder “what if?”, where, in other words, I see the world anew — instead of marveling over some mundane details of a world that isn’t that exciting to begin with. (Your mileage might vary.)

Maybe it is my background in the sciences that has me ask artists for more than a mere collection of facts (let’s call it that). As a scientist, that’s what I was doing: collecting facts and coming to the only conclusions that were supported by those facts. There’s nothing wrong with that; but with time I found it wanting, especially since it put a limit on what I think of as my creativity.

Thus, now I want artists to get me more: as I already noted above, I want them to make me imagine something that’s not supported by the facts, or maybe something that’s supported by the facts albeit in a fashion that has me reconsider what I thought I knew.

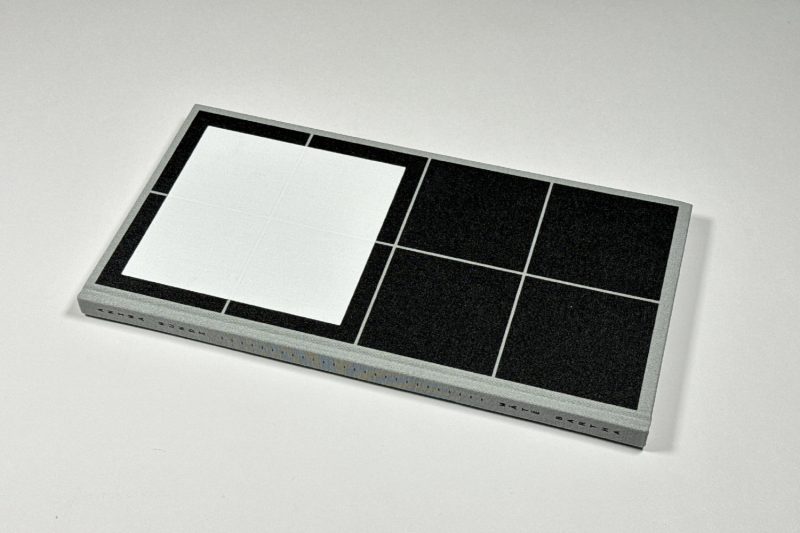

It’s along these lines that Máté Bartha‘s Anima Mundi operates. Designed very attractively by Carel Fransen, the book is an exercise in making sense of the world through patterns either observed in it or placed onto it (design, of course, is information of visual material towards an end: communication).

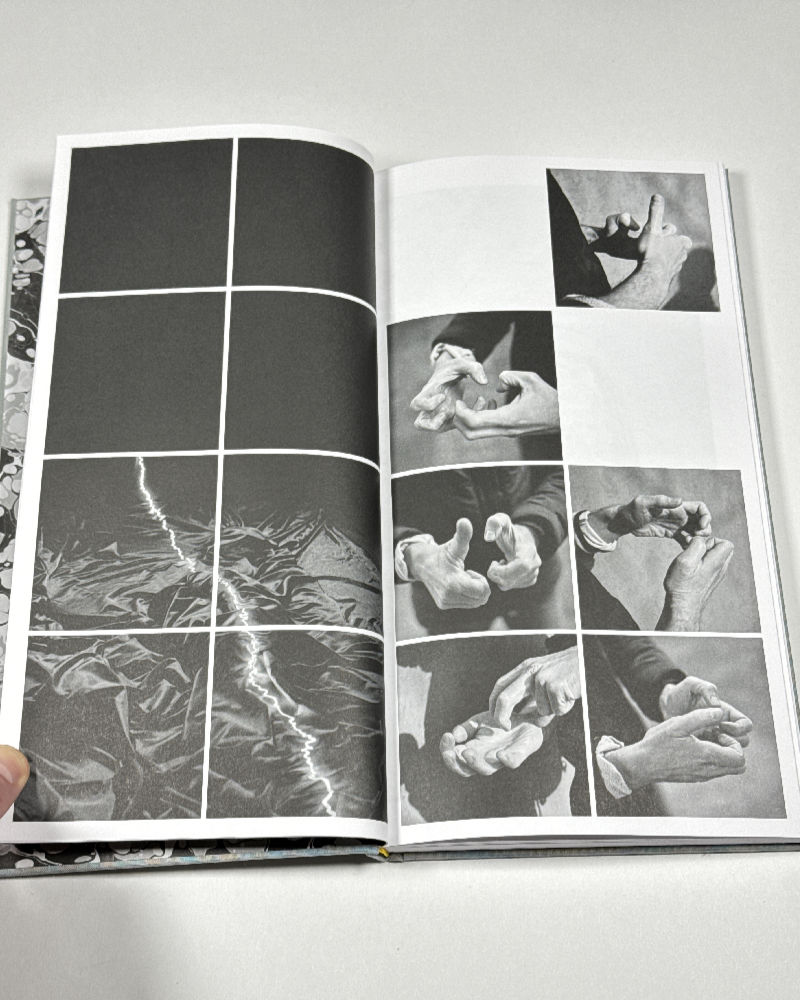

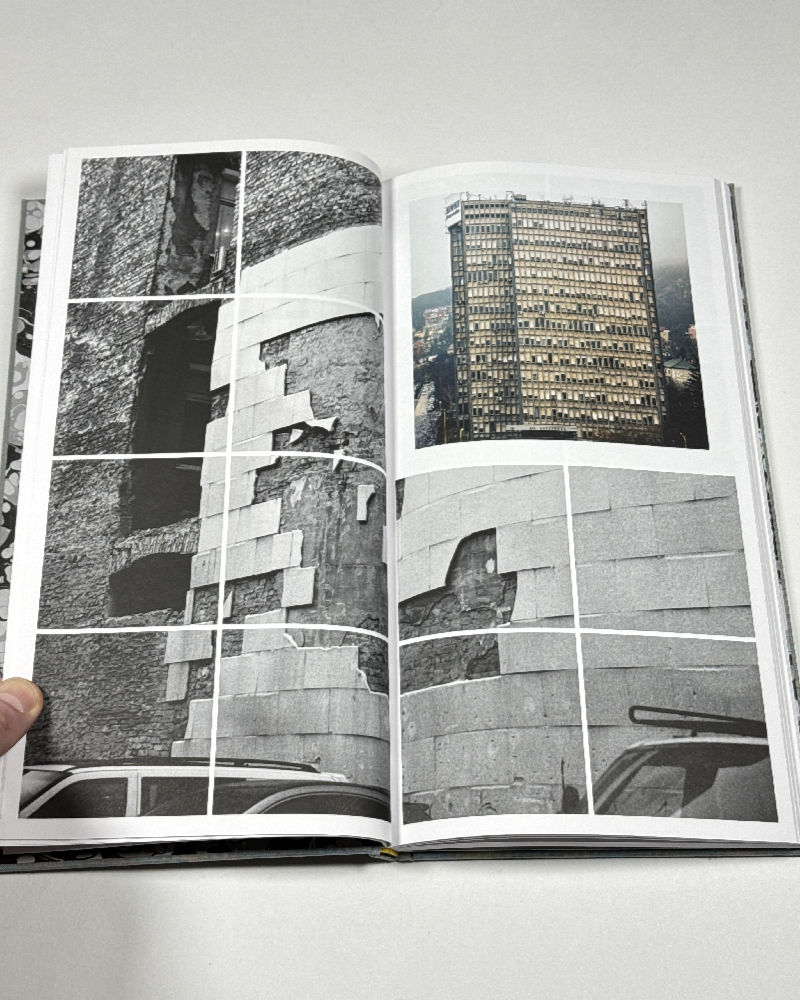

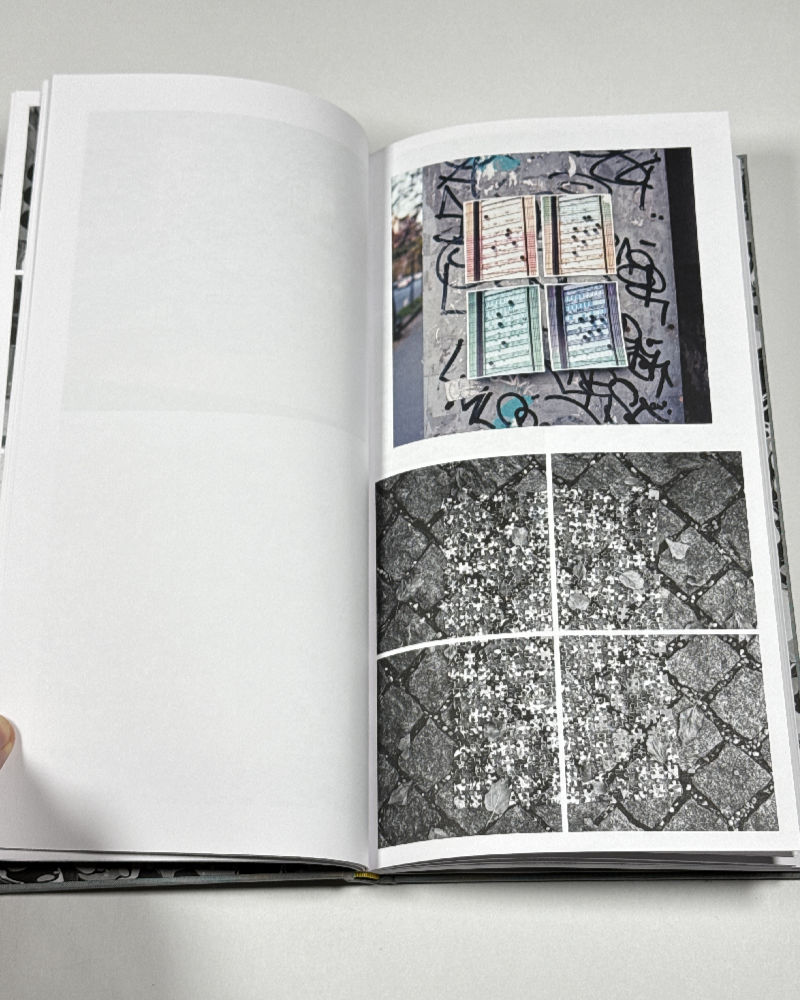

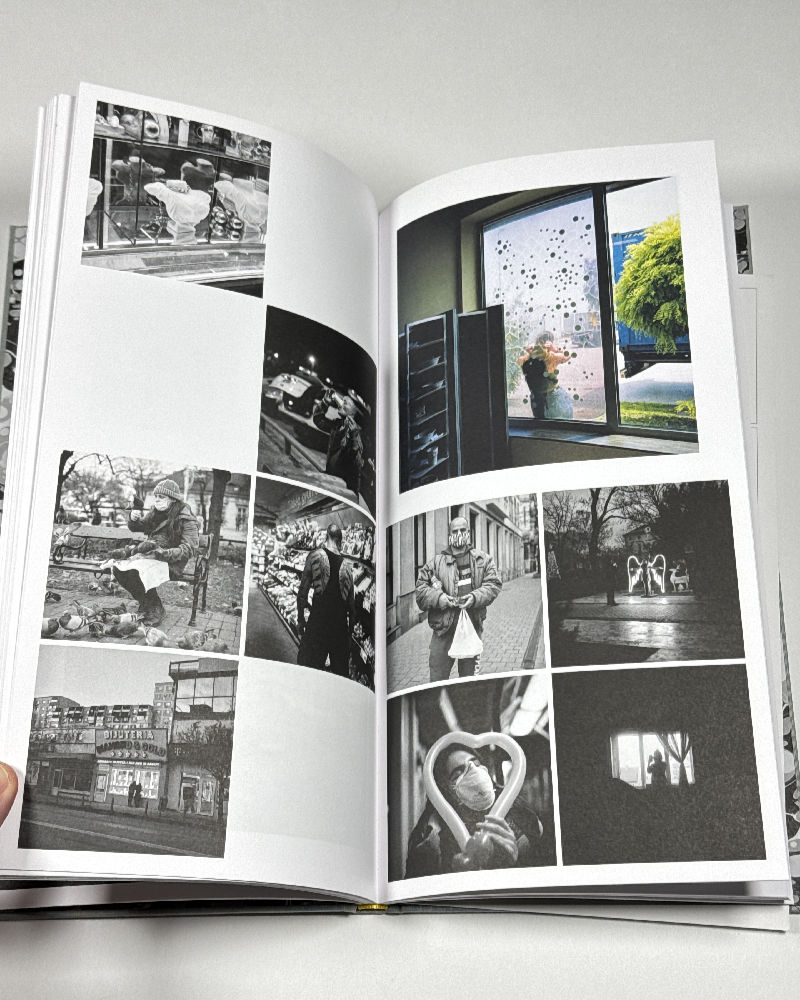

Here, it mostly relies on a pattern of eight square-shaped boxes on each page, into which photographs are being filled. The individual photographs either fill a square, or they might fill a larger number. Where they fill four, they might be presented as four individual segments, or they are shown as a whole (but slightly smaller than the grid of four).

None of this would work if many of the photographs themselves did not depict patterns: the fragmentation of information serves to re-shuffle what is on view and its accumulation hints at a logic that might or might not be one we are not familiar with. I suppose this latter part strongly depends on who the viewer is; someone trained in the sciences might experience this book very differently than someone who is not.

(Which fact of course might make me the wrong person to write a review of this book. But now that I have started the job I will finish it.)

Without the inclusion of photographs of the human form, Anima Mundi would be a dreadful affair. Thankfully, there are quite a few of them, including a number of pictures of two hands used to form what might be symbols of some kind. Meaning, this says, is being communicated here and in what follows. What that meaning might be is up for the viewer to find out.

In many ways, you could view the book as a fairly representative example of a lot of work that is being made these days. It’s cerebral and very well made (I don’t mean “cerebral” as a criticism), and it talks about a bigger loose scheme while ignoring all the very concrete ones that surround us (and that I do mean as a criticism).

At some stage, photographers collectively will have to decide whether re-arranging the pixels of the deck chairs on the Titanic really passes the test of our times. Then again, Bartha lives under the Orbán regime in Hungary, so my comments are really directed at all those photographers who are still able to enjoy their civic and artistic freedom.

With that said, Anima Mundi certainly is one of the best recent photobooks that operates around the idea of (loosely) using the scientific method to make us re-consider the world. Looking through the book makes for an interesting experience: with some photographs, I felt that seeing them only in the grid made them lose some of their inherent value. But with others, it was the exact opposite.

Which only proves that when it comes to the photobook, the only thing that matters is the whole — and not the constituent parts. And that’s more or less the point of the book as well, even as it’s not announced what that whole might be: it’s up to the viewer to create it in their head.

Anima Mundi; photographs by Máté Bartha; essays by Emese Musci and Paul Dijstelberge; 136 pages; The Eriskay Connection; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!