The world of documentary photography adheres to rules that borrow heavily from traditional journalism. With few exceptions, the (typically outside) observer enters a space or approaches a topic with the idea of providing as objective as possible a picture. Obviously, true objectivity cannot be had — humans aren’t robots. The smart documentarian will acknowledge as much and proceed with this inherent contradiction of her or his endeavour in mind. Conclusions and/or judgments might be offered, but even they tend to usually end up being on the cautious side.

There is much to be said for that model, as we are all learning these days as alternative hyper-partisan outlets undermine everything traditional journalism has come to stand for, to disseminate what can only be described as blatant propaganda.

At the core of all this stands the idea of truth. Absolute truth is unattainable — this might be the only thing even the most extreme poles of human endeavour, religion and science, can agree on. In a nutshell, aiming for as much objectivity as possible is an attempt to get as close to a incontestable truth as possible, without ever being able to fully reach it. Ignoring those hyper-partisan outlets (which act in bad faith as far as the greater good is concerned), objectivity is not necessarily the only way to reach a — note: not the — truth. After all, there are many kinds of truths: human life is too complex to make do with just one.

I’m personally very interested in expanded explorations of the documentary form because I believe that insight into the human condition needs to acknowledge the many grey zones. This is not to say that I deny the value and/or validity of traditional documentary work — quite on the contrary. But I’m intrigued by having what I believe in challenged not just through facts but also through an exposure to the unexpected.

Christian van der Kooy‘s Anastasiia is a prime example of a recent book that pushes the boundaries of the documentary form. It does so by explicitly incorporating aspects that I suspect many documentarians would shy away from. On a trip to Ukraine, the location explored in the book, the photographer met a young woman who for reasons that aren’t entirely clear picked him up at some metro station. They fell in love. The developing relationship immediately becomes part of the overall narration — a long-distance relationship, sustained through the exchange of messages and through Skyping.

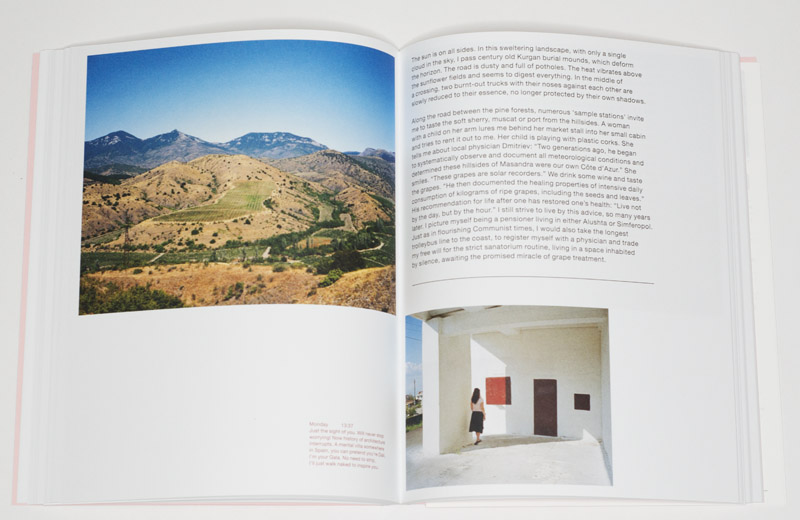

While the relationship plays a large part, the book does not center on it. Instead, its focus is the country, Ukraine, and its recent (and ongoing) turmoil, caused by the overthrow of a corrupt regime and the subsequent Russian invasions in Crimea and eastern provinces. Throughout the book, both the photographer and his girlfriend attempt to come to grips both with the country itself and their relationship, both providing their own voices through text (curiously, Van der Kooy’s messages to Anastasiia are absent). For the photographer, it’s an attempt to come to grips with another country that, while being part of Europe, feels alien. For the young woman, the challenges are not that dissimilar as what used to be taken for granted is now being challenged, and old ideas and norms are being replaced by new ones.

The mix of the intensely personal with what one would consider documentary material in addition to the mix of two clearly distinct voices (that also try to make sense of each other) lends the book a dimension absent from many (actually most) other documentary photobooks I know. There is a clear red thread running through the book, but it’s one of human uncertainty and of longing. It’s a book about life under specific circumstances, two people living their lives while being close to each other — mentally close when not being physically close. Can a country be understood by any one person at any moment in time? It’s doubtful. There can always be a picture painted (or written — should historians read this review), but inevitably, the picture will change.

The material in the book is presented and organized through some very basic and simple design choices, making the viewer’s/reader’s job very simple. Skype screengrab images are monochromatic — the pinkish hue that can be seen on the cover. Anastasiia’s writing and text are presented in the same colour. In contrast, Van der Rooy’s photographs are shown in full colour, and his writing is black.

I was unable to read Anastasiia in one sitting, something that would have been easily possible, simply because I didn’t want the experience of spending time with the book to end. I can only say that for very, very few photobooks that arrive at my doorstep. As much as I am tired of the seemingly endless barrage of very personal work in photoland — to give just one example: how many more family-photography projects do we need?), here I felt I was in the presence of something not only unexpected but also deeply engaging, deeply affecting.

It’s very likely that my placing of the book into the larger context of documentary photography will have a lot of people disagree. In my photobook taxonomy, I placed it under subjective documentary. But I do think there’s a time and place for an expansion of the idea of what the documentary form is and can be, in part because of the propaganda counter push by the hyper-partisan outlets: one of the most problematic aspects of the documentary form is its insistence on as objective a truth as possible. Hyper-partisan outlets have been deftly using this Achilles heel by pointing out minor inconsistencies in other people’s reporting while themselves pushing blatantly false if not outright nonsensical material. Whether or not the fight against those acting in bad faith can be won remains to be seen.

One way to disarm the partisans and professional liars might be to opt out of playing this one-sided game and to, instead, embrace forms such as the one used in Anastasiia. This not only expands ideas of the documentary to include other voices, here that of a person living in the area in question, but it also acknowledges the inherent shortcomings of the documentary form while not giving up on the quest for a larger truth anyway.

Highly recommended.

Anastasiia; photographs by Christian van der Kooy; text by Christian van der Kooy and Anastasiia [last name not given]; 160 pages; The Eriskay Connection; 2018

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.2

Ratings explained here.