I have never been particularly interested in street photography. Of course, I am aware of its dominant past practitioners. Their work speaks of a certain moment in time (and space: mostly New York City) that has long passed. I find it difficult to ignore the very strong whiff of machismo around those photographs.

Street photography today mostly reminds me of what reenactors do: instead of donning some old uniform to re-stage some battle (let’s not get into the baggage of that), you put a camera around your neck and re-imagine the glory days of the photographic discipline you admire so much. It’s fine if that’s your thing: who am I to argue with that?

Except that today, many (most?) people do not want to be photographed without their consent. The US defense of the public space in which you operate and that gives you the legal right to do so does not address the ethics of it. The European Union has stricter laws and protects its citizens’ right of their own pictures. There are legal exceptions for artists (that differ from country to country), but the ethical aspect remains.

Of course, what defines an artist is not that they do what they want to do. The defining criterion of a real artist is that they create something around and against the restrictions they find themselves facing.

The following is a relevant and important question not just for street photographers but for many other practitioners as well: how do you create a form of whatever type of photography you’re using that does not merely reproduce simulacra of bygone eras? The idea is not to create the new for the sake of the new (in a neoliberal, consumerist sense), but instead to create the new for the sake of it speaking to the moment artists are finding themselves in?

Maybe it is no surprise that one possible answer for street photography would come from Japan. Tokyo, after all, has been undergoing changes since, say, the 1960s that are a lot more massive than the ones you’d be able to observe in New York City, both in terms of what the built environment looks like and the overall embrace of technology and public investments into civic infrastructure. At the same time, consumerism plays an outsized role in both cities.

What might a street photography look like that accounts for all of these massive changes and that brings the genre into our own time? If you’re curious, Fumitsugu Takedo will show you in his book Ambience Decay (the artist’s website is almost entirely in Japanese, but there is enough English text for a viewer to understand what’s going on).

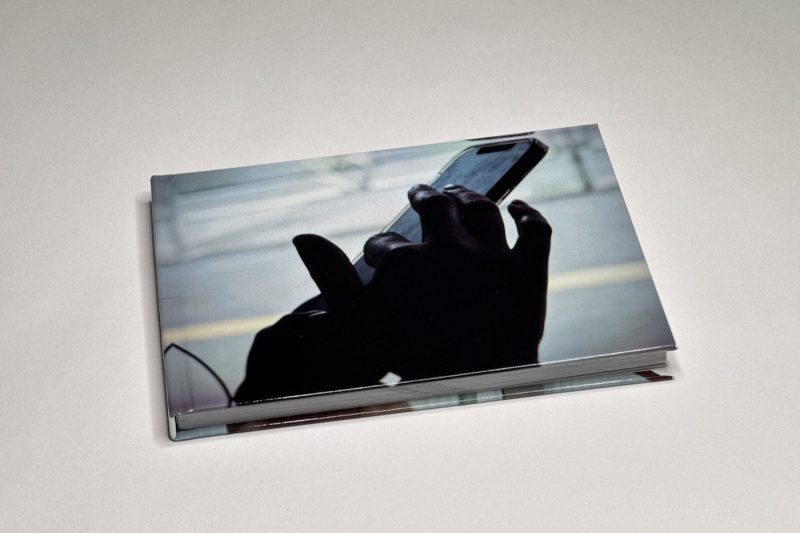

I can’t tell whether the book was produced using a mass-market printing service (some equivalent of Mixam). For most photography applications that I can think of such services don’t do a particular good job. But here, the production matches the world presented in the book really well. I have seen my fair share of books produced this way, and I’ve always come across being underwhelmed. Not here.

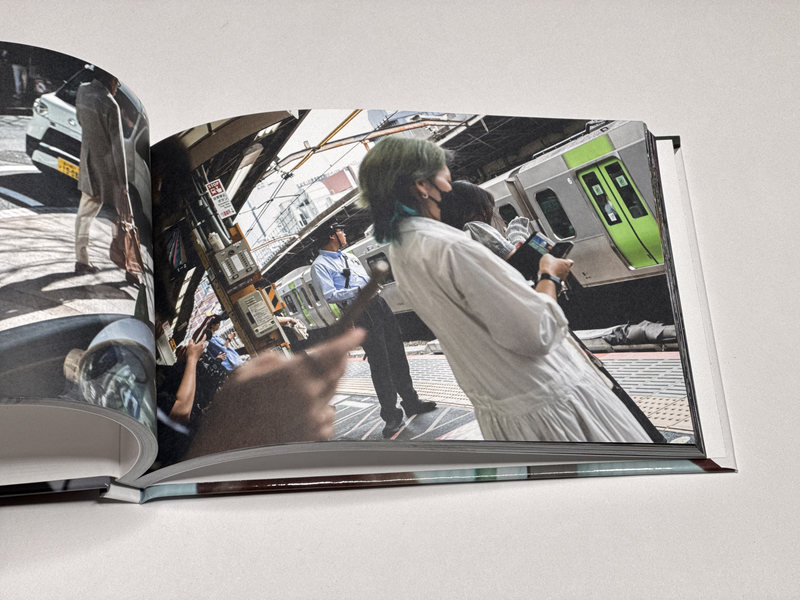

One of the defining aspects of Ambience Decay is not only an embrace of different types of images and image sources, it’s also its rejection of old-fashioned ideas of image quality. By that I mean that blown up details of digital images (that might or might not betray compression artifacts, screen-raster details, or gaudy overly processed colours) exist next straight photographs of a mostly completely helter-skelter kind.

Looking through the book, I was immediately transported back to the busiest and most crowded sections of Tokyo, with its throngs of people on their ways to whatever destinations they were heading towards. The whole book is filled with the city’s nervous energy.

Interestingly, the most prominent aspects of the book are hands, many of them holding and/or operating smartphones. It’s the hands of people encountered in the streets. There barely are any depictions of them following the tradition of the genre. Instead, they’re lost in the urban jumble around them, cut off through the cameras’ framings, obscured by ubiquitous reflections created by store windows and the displays of advertizing.

If traditional street photography portrayed life through its skillfully seen temporary arrangements of individuals navigating their city, here the city has overcome its own inhabitants. Whatever individuality the people in the photographs might have within the confines of their own homes, there is nothing left in an environment that not only culturally negates the individual: capitalism, despite its hollow promise of iThis and iThat, does so as well.

We have all become expendable, and nothing but the content of our bank accounts is of interest.

I find it unlikely that the practitioners of traditional street photography will recognize a contemporary version of their beloved genre in this book (I could be mistaken). But for the rest of us, Ambience Decay demonstrates that as a medium, photography can be driven forward and brought into this moment — not through snake-oil style offerings coming out of Silicon Valley (such as “AI” image making) but through the ingenuity of its practitioners.

There is a lesson here, even though I do not want to overstate the case: if you believe that you will create good art by seeing which prompts will deliver you the best images, you might be operating under the wrongest possible definition of what art is. Operating within the confines of a box is not what makes good art (and that’s not even getting into the many deeply problematic aspects of “AI” image making, such as the plundering of visual resources and the many biases against people who are not straight and white).

Good art that pushes the boundaries and that drives its own media forward is made by operating outside of the confines of the boxes, whether the ones created by the technology available to you or the ones created by whatever society you might find yourself living in.

To reinvent the moribund genre of street photography by bringing it into our time, both in terms of image making and looking, is no mean feat. But here it is, Fumitsugu Takedo‘s new street photography, produced in sterile consumerist Tokyo.

Highly recommended.

Ambience Decay; images by Fumitsugu Takedo; 120 pages; Photobook Daydream Editions, 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!