For a while now, I have been looking into photography that moves away from the single-image paradigm. Per se, there is nothing inherently wrong with showing single photographs and building up larger units from those (in the form of the usual editing and sequencing). However, the approach is also oddly limited/limiting. Why should any one thing or any one person be shown with merely a single image?

I can see a number of problems with the single-picture approach, especially since it is too tempting to pick the photographically “best” picture from the source pool (whatever your definition of “best” might be). This approach, in turn, reduces depicting the world as seen through photographic gems — essentially working with the world (if it’s lucky), but usually mostly against it. Unfortunately, the model of the artist as the the brooding, singular genius still is too prevalent for the discussion of what photography is and how it can be used to open up more.

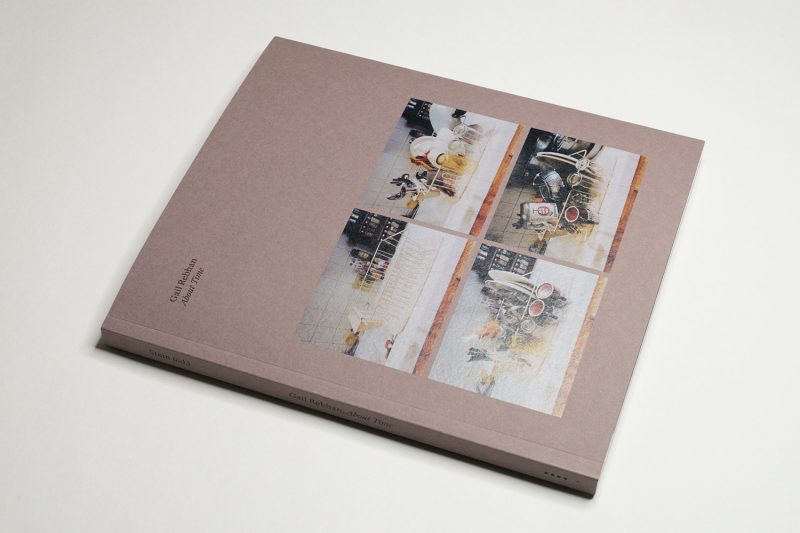

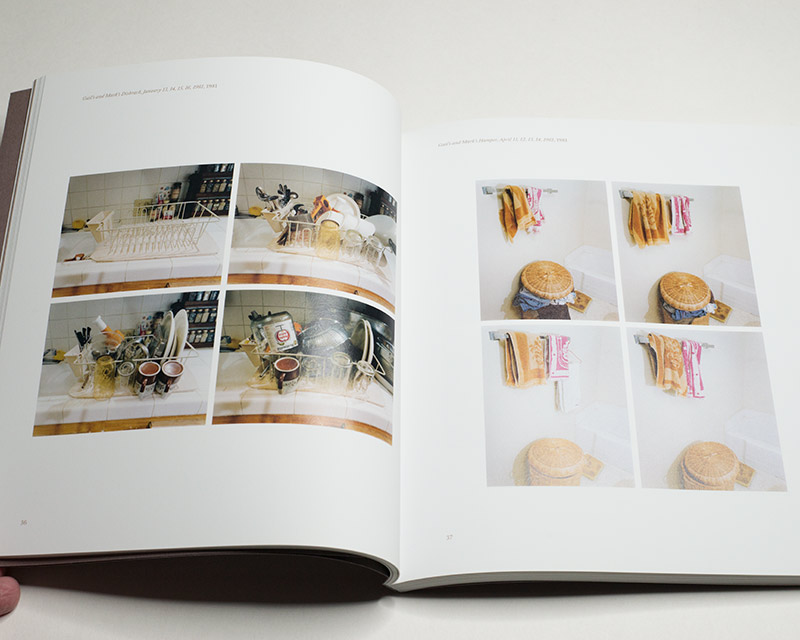

With that in mind, it’s probably no surprise that I was pleasantly surprised to see Gail Rebhan‘s About Time, a career retrospective edited by Sally Stein. The cover shows a grid of four photographs of a dish rack in various stages of its existence — empty and filled with assortments of dishes left to dry. This, we learn in the book, is a piece entitled Gail’s and Mark’s Dishrack, January 13, 14, 15, 16, 1981, taken from the very first section of photographs in the book.

There’s nothing particularly remarkable about any of the individual elements of the piece; you might even argue that that’s the case for the piece itself. Were you to do so, though, you’d basically arrive at a conclusion based on your original premise, namely that photography ought to be remarkable to warrant our attention.

It’s not necessarily that I want to argue that we ought to spend our time on the unremarkable. Instead, my point is that things can be remarkable if we pay closer attention without asking for exposure to singular photographic gems; and that is the point of most of the photographs in About Time.

As Stein makes clear in her writing that goes alongside Rebhan’s photo pieces, the photographer emerged at a time when second-wave feminism was at its heyday in the US. This sets the stage for the bulk of the work. The domestic setting here plays a major role — perhaps not surprisingly, because this is the most immediate ground where many of the issues feminism centers on play out in their first, most immediate fashion. In a heterosexual relationship, the task of taking care of the children (and, as is often the case, the male adult) almost inevitably falls to the female partner. If that partner also is a photographer, that poses a challenge for her, given she now has to juggle domestic work and her own work career.

This is a theme that I have encountered speaking with numerous photographers, some of whom had to put their career on hold when their children were so little that taking care of them took up all the hours of every day. As an aside, this is also the reason why the age limits that are still in place in many European countries for competitions and prizes are so toxic: they disadvantage women photographers even further — if you need to put your career on hold for a few years, something that many (most?) male photographers can simply avoid, how can you conform to an age limit of, say, 35? I find it infuriating that there is so little awareness of this basic problem in Europe.

Coming back to Rebhan’s work, the earliest pieces employ multiple images. They are either short sequences (for a lack of a better word), or they are the kind of collections (ditto) that show the same small detail from the photographer’s domestic life at different times of the day or on different days. There is very obvious feminist critique in many of these pieces, even if it is more obvious in some than others.

From late November 1983 until mid-July 1984, Rebhan recorded the progression of a pregnancy by taking a picture every day, the camera set up in front of a mirror and the photographer standing right next to it. There are a few blank frames where apparently, the camera malfunctioned. Given that the piece itself was designed to be the set of contact sheets, no second picture was taken. In light of the previous multi-picture work, this piece is an obvious consequence of the photographer’s thinking, and it’s most effective.

Later work shows Rebhan work with images and text. While I very interested in the ideas and themes explored in those pieces, my overall impression is that most of these pieces are too reductive. In most cases, the image elements serve as illustrations of what is expressed in the often very powerful text. As a consequence, the pieces themselves feel more flat than they might have been, had there been a different relationship between the text (which here clearly is the driving force) and the images.

I felt myself wanting to be able to read the text without the distraction of the pictures. I also felt that different pictures might have served the work better, especially if they had been given the space they could have used. Cramming everything into single panels doesn’t work for me.

We should all be so lucky to have a sympathetic and deeply insightful observer such as Sally Stein look into and write about our work. If you don’t know anything about Gail Rebhan and the world she grew up in, Stein has you covered. In much the same fashion, she unearths the ideas and themes in Rebhan’s pieces.

All of this is done in elegant writing that doesn’t attempt to bamboozle the reader with unnecessary jargon. As a consequence, About Time allows easy and pleasant access to a photographer’s world that, I think (or at least hope), will serve as inspiration for others.

About Time; photography and text by Gail Rebhan; text by Sally Stein; 144 pages; MACK; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!