“The book consists of images and words”, writes John Berger in A Note to the Reader at the very beginning of A Seventh Man. “Both should be read in their own terms. Only occasionally is an image used to illustrate the text. The photographs, taken over a period of years by Jean Mohr, say things which are beyond the reach of words. The pictures in sequence make a statement: a statement which is equal and comparable to, but different from, that of text.” (my emphasis)

These few sentences succinctly summarize how this photo-text book works, how it is to be approached. They apply equally to many other instances where text is used in photobooks. If you were to make such a book — or maybe collaborate with someone, printing these sentences and hanging them in a prominent spot would do you no harm: these are the pictures, this is the text, this is what they do on their own, and here is how they’re made to dance together.

When we lost John Berger, we lost a man who was able to express complicated things in a simple, concise manner. We also lost a man who was not hiding his convictions. In the Preface of the 2010 reissue of the book, he talks of the “global economic order, known as neoliberalism”, and he clarifies: “or, more accurately, economic fascism.” After all, Berger was a Marxist. If you want to learn more about the man, read Joshua Sperling‘s marvelous A Writer of Our Time: The Life and Work of John Berger.

Right before the Preface, there is a page with a little bit of text. It says: “This book was made by: Sven Blomberg, painter; Richard Hollis, designer; Jean Mohr, photographer; John Berger, writer” (I condensed the text into a single line). Mohr was the main photographer, but Blomberg also contributed photographs and, with Richard Hollis, helped build the book’s visual structure.

Hollis, of course, famously designed Ways of Seeing, but he also wrote a lot about design. If you’re interested, you can’t go wrong with About Graphic Design. Not that this fact should really matter but A Seventh Man was created by a few giants in their respective fields.

When I called the book photo-text above, I maybe should have been clearer. In all likelihood, someone opening it will approach it as a text-photo book. You could merely look at the pictures, and that would give you some idea of what’s going on. But it really is the text that carries the book, despite Berger’s initial implied insistence that text and pictures are equal. Or maybe it’s not implied at all, and I’m reading this into his words.

In his 2010 Preface, Berger points out that many elements of the world as we see it now are absent from the book. It is true, economic migration now looks a lot different than it did in the late 1960s or early 1970s when various Western European countries (including my native West Germany) invited “guest workers” to temporarily migrate north and to work in factories.

Nowadays, economic migration is mostly unwelcome — in Europe as much as in many other parts of the world. What is more, many of those who migrated to Germany (to take this case) stayed there, having children, and forming a community that is still struggling to be fully accepted as being an equal part of contemporary Germany.

The fact that these details have changed shouldn’t get in the way of the overall focus of the book. We could easily surmise that a migrant’s overall motivations and background now are very similar to those a migrant might have experienced almost 50 years ago. Also, as the title page informs us, A Seventh Man is “a book […] about the experiences” of migrant workers. It is, in other words, a form of humanistic Marxism.

Such an approach promises much. It invites the reader/viewer to participate in these experiences, to the extent that that is actually possible. Such a participation could possibly bridge the gap that exists between readers/viewers faced with purely documentary work, where more often than not someone else ends up as a scientific specimen than a fully formed human being on their own (obviously, there is the big possible problem of othering).

However, it’s not entirely clear to me to what extent Berger and Mohr actually succeeded in arriving at their goal. Actually, the onus here is on Berger, because by construction, the photographer cannot depict his subjects’ mental state. The writer, however, attempts to do so, writing about the migrant in an omniscient fashion. There’s the “he”, the archetypical migrant whose motivations are laid out as if the writer had had full access to them.

(Berger acknowledges the omission of the experiences of women in A Note to the Reader: “Among the migrant workers in Europe there are probably two million women. […] To write of their experience adequately would require a book in itself. We hope this will be done. Ours is limited to the experience of the male migrant worker.”)

As much as I appreciate the book, it is these “he” passages that to me feel a tad too paternalistic, however well Berger actually meant. Even if every word in these “he” passages was created from something a migrant might actually have said to Berger (or Mohr), I find the conversion into an omniscient narrator’s description of another person’s motivations troublesome. In the end, while these millions of migrants might share very similar experiences, taking away their individuality and turning them into a generic “he” ultimately serves a purpose that could easily be compared with, let’s say, the way they’re inspected by doctors at the beginning of the book.

Sentences such as “He is not aware of his historical antecedents.” (p. 115) rub me the wrong way. I find myself surprised that someone as astute and political a writer as Berger would not pick up on what he was doing with his words. Even if the migrants had no idea of “historical antecedents” (and, let’s face it, Berger’s Marxist thinking), to phrase it this way only reinforces their overall standing. Other examples are more benign, yet often hardly more endearing.

So A Seventh Man is not without its problems. Still, it’s a book that deserves to be read and viewed and studied by all those who want to use the combination of text and pictures. It’s a book that is overtly political when so many text-photo books now shy away from that.

What is more, migration, whether economic or any other, still is a very big topic, albeit one with a variety of changed circumstances. The book’s basic premise concerns us as much now as it did back when it was published.

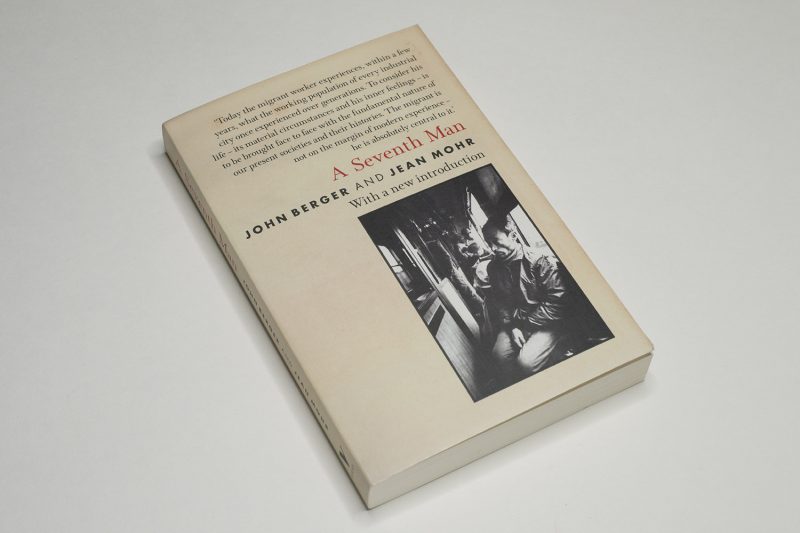

A Seventh Man; text by John Berger; photographs by Jean Mohr (and Sven Blomberg); 248 pages; Verso; 2010 (reissue)

In Hindsight dives into the existing world of the photobook, specifically into all those books that were published years ago and that now exist in libraries — or somehow were forgotten and are thus never talked about. Much like wine (or the rest of us), books age — some become more meaningful, while others betray their age, leaving a sour taste in everybody’s mouth. In Hindsight is an attempt to pull a few old books off the shelf, to see if and how they hold up to scrutiny.