There are many artists working with found/vernacular photographs. At this stage, it would probably be possible to compile a rather large book around the topic. While I enjoy looking at vernacular photography, I don’t think that most of the art produced around it is all that interesting. The main problem is that the source material already is so interesting than adding anything on top or doing something with it is really difficult. An image or two typically might look interesting — whether it’s some graphic-design exercise or some embroidery on top. However, once you’ve seen more than a handful, the “oh, I get it” factor kicks in, and whatever was layered on top of the source material turns into a shtick.

If I had to pick an artist as an example who doesn’t fall into this trap it would be Cai Dongdong. In a number of ways, the Chinese artist has more in common with, let’s say, John Baldessari than with any of the other artists working with vernacular photos who have made a name for themselves. Much like Baldessari, Dongdong is smart and often very witty in his work. Whereas other artists are content with assembling large sets of vernacular photographs, the collection of such pictures is his jump-off point. Just like in he case of Baldessari, the occasional designs that are being constructed with or on top of photograph are means to an end — and not the end itself.

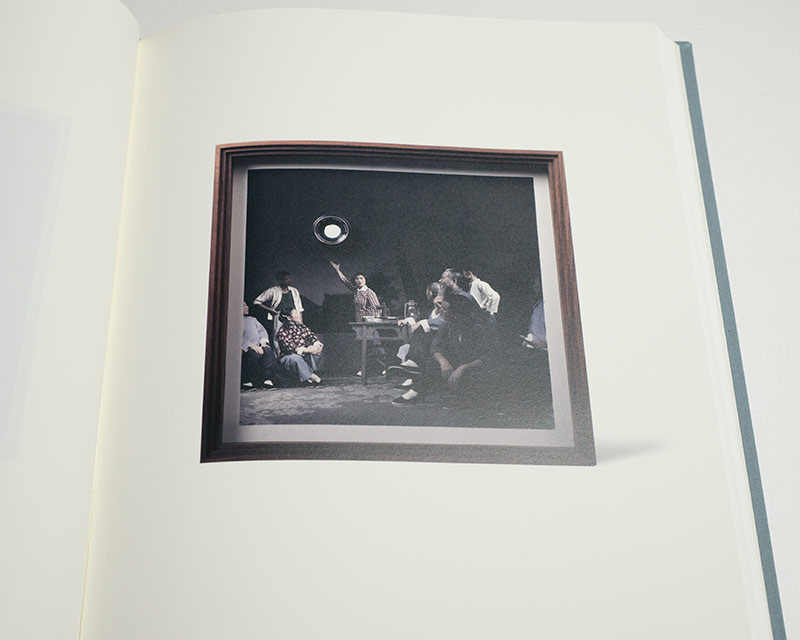

There are a number of strategies employed by Dongdong. One of the most Baldessarian is to use part of a source photograph’s element and to amplify it in some fashion. For example, a photograph of a group of young men engaged in a rope-pulling contest is framed and then hung on a wall with a rope in such a way that the rope in the picture and the one in the gallery appear to connect. This example includes another element, namely the use of space and the photograph as an object. Often, the photograph’s content is made to extend out into the world (such as when in front of a photograph that shows some rocks, there is a small platform with little rocks placed on it). Alternatively, the fact that what we are looking at is a photograph is driven home in some way.

Photography as a way of looking and of creating an image is another very prominent strategy. Camera lenses appear both as added (Photoshopped) elements of photographs themselves, or they are added to a photograph. For example, one source photographs shows a naked man and woman in bed. The scene must have been photographed by the men, who is looking down towards his crotch. The woman is holding his erect penis, which has been replaced with a camera lens.

In many of his works, Dongdong essentially connects many of his photographs back to the world from which they were taken. Whoever is depicted in them is brought back into our three-dimensional world. Our and their looking are connected. Staring into that camera lens grabbed by the naked women makes for a strange experience: how can the picture (or maybe the penis) stare back at us? Or maybe observe us observing it?

In all of these cases (and much like in the case of a lot of Baldessari), it would be asking too much to read a deeper, more profound meaning into the work — a meaning beyond what the work itself gets at. The wit is the point; the amplification of what a camera does (and all of the consequences arising from that) is the point. It is not for nothing that a new catalog of the work is entitled A Game of Photos.

Much like how Baldessari played with conventions of film and photography to make us look at what we actually believe in and how we tell stories, Dongdong uses a similar approach to have us look at what photographs do on their own. The childish delight in both artists’ work appeals a lot to me. Much like children, both are not afraid to employ serious photographs for decidedly unserious means. But that is exactly the strength of these two artists, in particular given how devoid of humour the world of photography is and how seriously it takes itself.

But the interventions of looking also remove the source photographs from — for a lack of a better word — the history to which they seemingly are confined. We are used to looking at photographs as these entities that show us people or things that were and now are not any longer. Breaking this idea gives the photographs, and by extension the people in them, a strange power that ordinarily we don’t expect to run into when looking at photography.

In the Baldessarian sense, this results in the ideas and thoughts we have about photography being broken, to have us re-engage with pictures. In some strange and rather light-hearted sense, this is a form of critique, whose target is the audience — and not the original photographers (whoever they might have been). Seen that way, there is considerable profundity behind all the visual mayhem after all.

A Game of Photos; photographs and installations by Cai Dongdong; essays by Karen Smith and Cai Dongdong; 214 pages; self-published; 2021

NB: I haven’t been able to find a link for the book. I will add one if I can find one later. The book lists the artist’s studio email — if you’re interested in the book try it.