How do you re-narrate the totality of someone’s life, whether your own or someone else’s? It would seem that providing as much detail as possible will help an audience understand the person in question. But as Édouard Levé demonstrated in his book Autoportrait, the accumulation of the most precise and minute statements only produces an incredibly compelling and magical piece of art, without bringing a reader any closer to the lived reality of the author’s life.

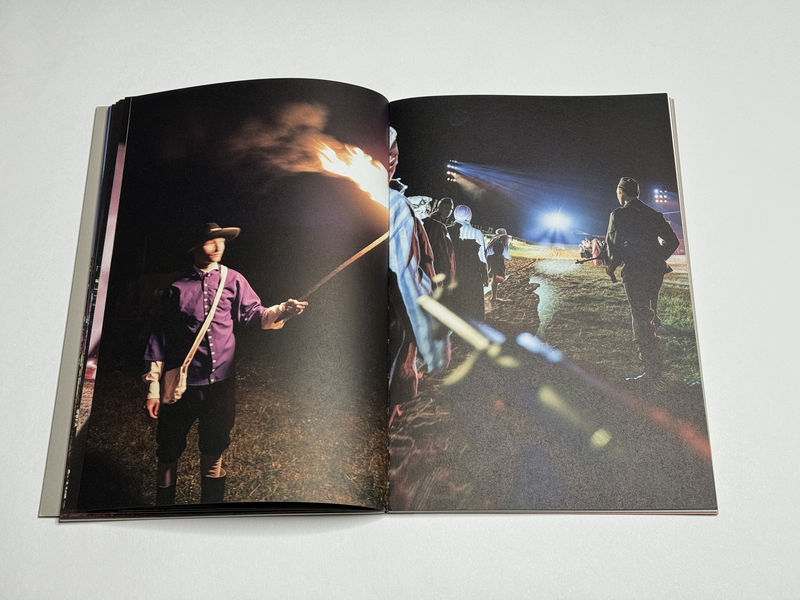

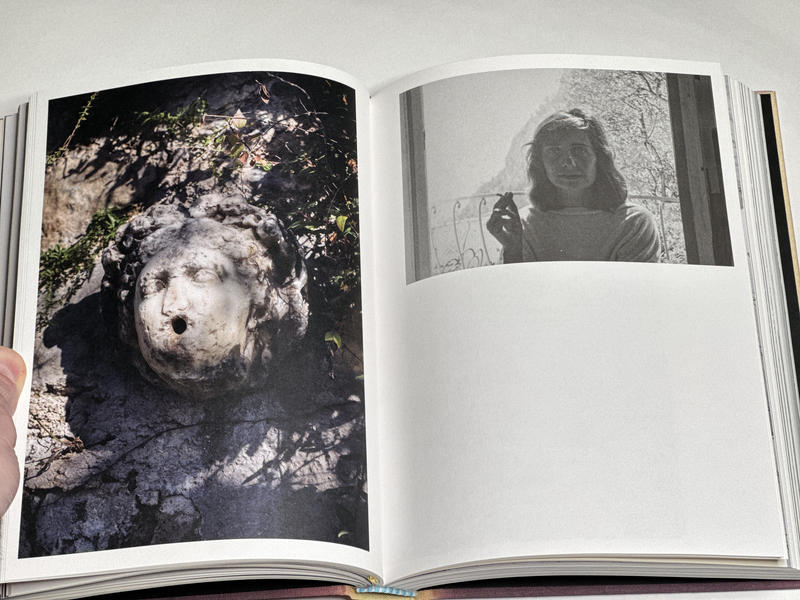

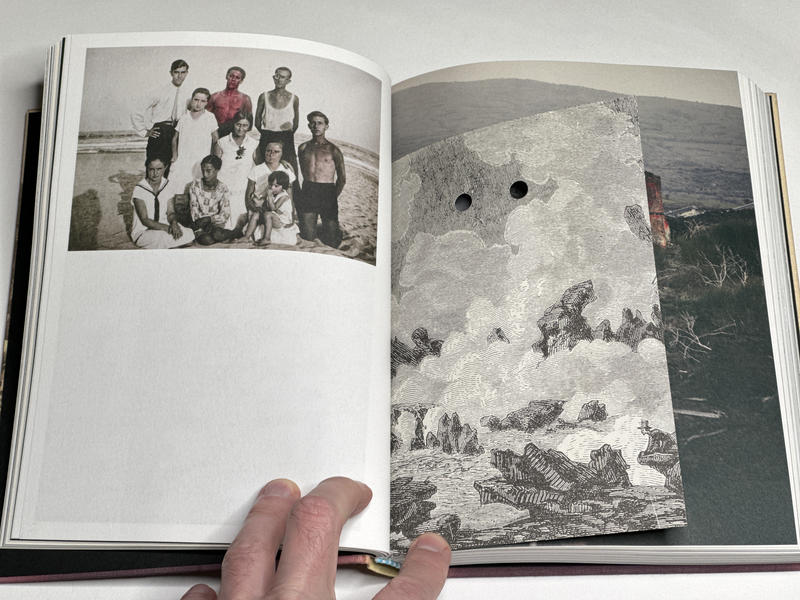

Photographs add a complication to the already fraught task of narration, given how mute they are. It’s not the trite fact that they only show surfaces; instead, it’s their completely fragmented nature that makes them such cumbersome entities to work with when biography is the intended end result.

Photographs are puzzle pieces that typically do not connect with each other. The best you can hope for when working with them is the creation of a mosaic.

There is much to be said for such mosaics, though, especially in light of the ultimate futility of attempting to re-narrate someone’s life: if, as is obvious, a life cannot be re-narrated truthfully, whether on an atomic Levé level or a much larger one, the deliberate exclusion of a life’s aspects (“facts”) can serve to create the larger whole. And words — written text — can fill the role that plaster plays in a physical mosaic.

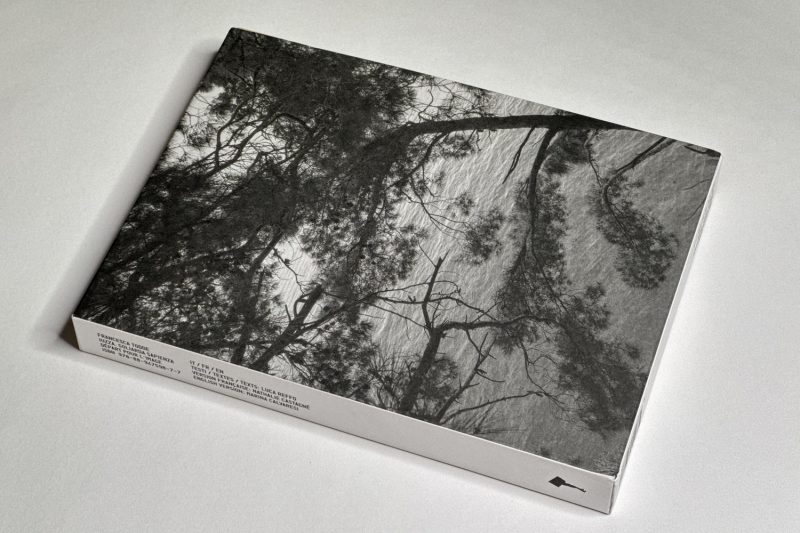

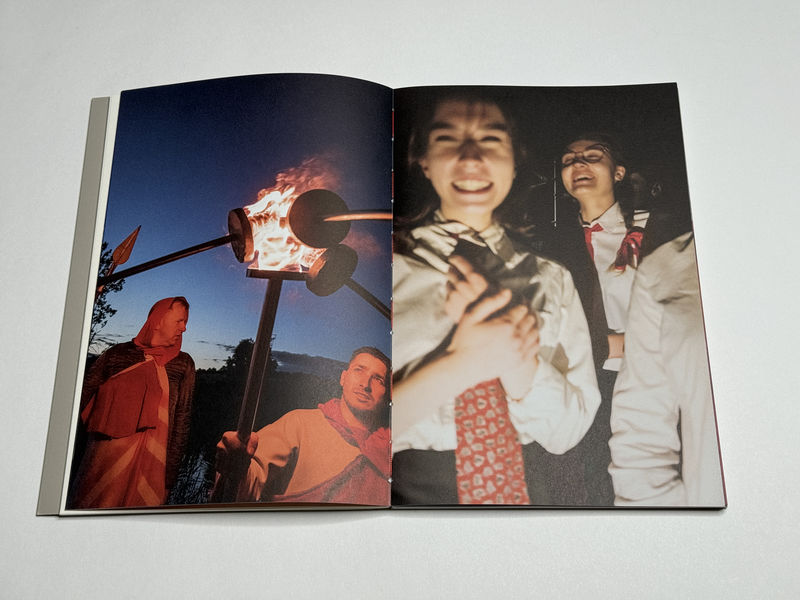

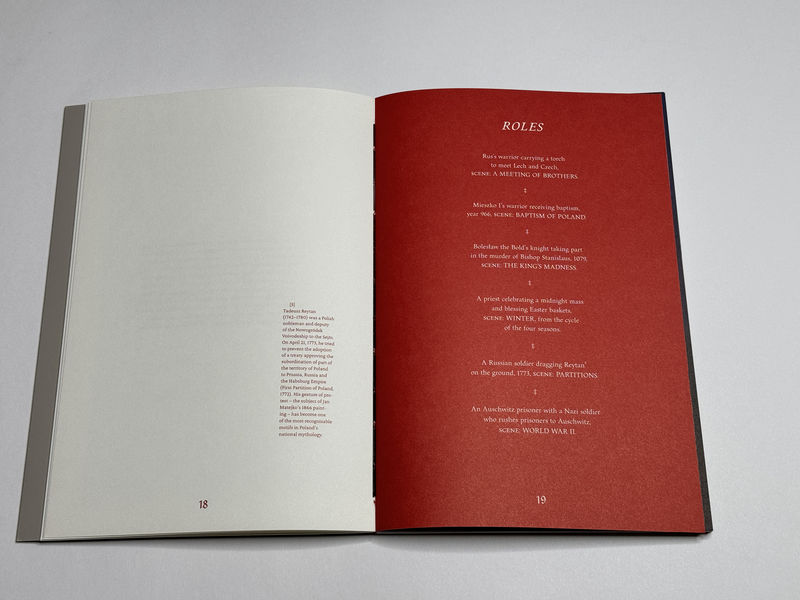

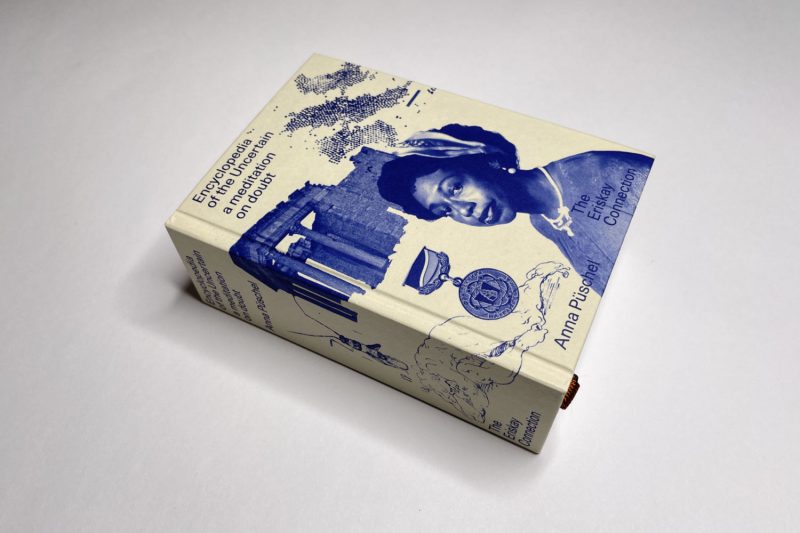

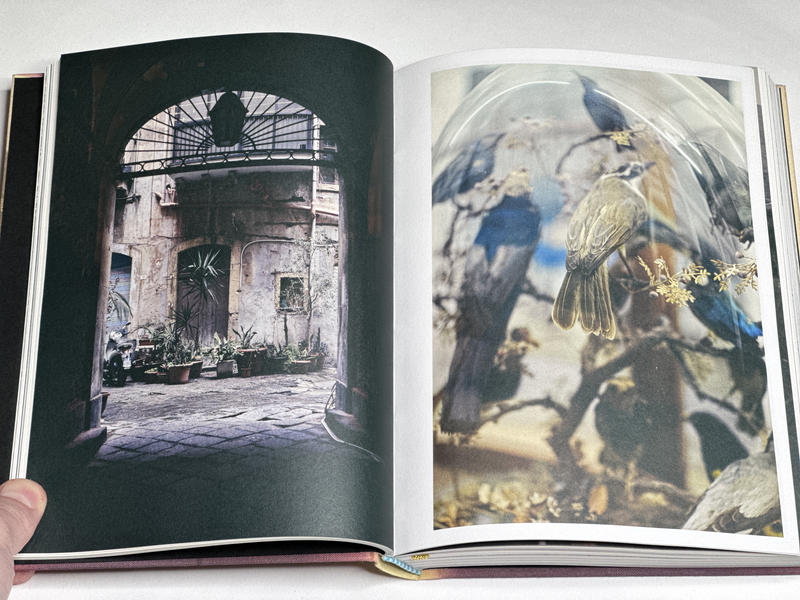

Francesca Todde‘s Iuzza relies on photographs and text to re-narrate aspects of the Italian actress and writer Goliarda Sapienza‘s life. There are seven chapters, each with its own particular focus. The bulk of the text comes at the end of the book, even as it refers to some of the visual elements presented earlier.

A disclaimer: I was not familiar with Sapienza. While I know a few things about Italy, I ended up feeling that I probably do not know enough about either the actress/writer or the country to be able to fully understand the book. I do think that the book probably relies on an audience that has more knowledge about its topic than I am able to bring to the table. You will want to keep in mind.

This is not to say that I did not enjoy spending time with the book. I did. As is the case for all of the books made by Départ Pour l’Image, a relatively new publisher based in Italy, the book has been produced with a lot of attention to detail, and it features wonderful photography.

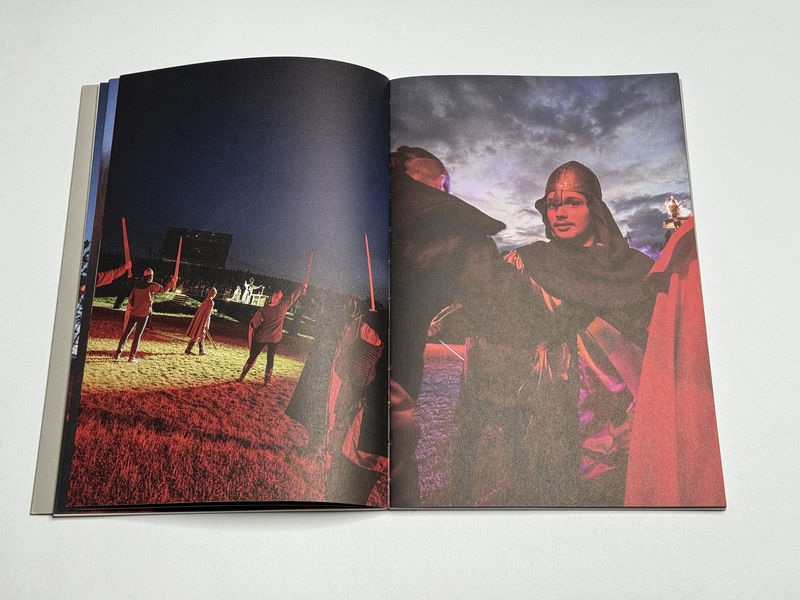

Given my relative ignorance of the main topic, I probably picked up a few notes more than others. In particular, there is a pervasive feeling of sadness throughout the book, a feeling of melancholia. At any given moment, I thought, it could tip into something much more severe.

I have been to Italy numerous times. As much as I enjoy the country — how could one not when surrounded by so much culture and a real appreciation for good food and drink? — the inevitable presence of the country’s past always had me on edge. You might imagine the country being a gigantic theme park, and there certainly are areas that feel like that. But historical sites and buildings are so common that outside of the very touristy areas, they still cast their shadows.

Maybe there is something to be said for the stereotype that if you are born in Germany, some of the ideas of Romanticism will inevitably become ingrained in your psyche: the idea that decay and beauty combine in a fashion that might reveal a dark side any time soon. Maybe that is what I connected with on my trips to Italy and when looking at this book.

Some of the text in the back of the book informs me that Sapienza did indeed have periods where her mental health deteriorated, with severe depression playing a role. This is not sadness, and it is not melancholia. It’s something else entirely.

Thus with this book, I am bringing certain aspects to the table — a history of depression and that German Romanticism I mentioned above. What I’m connecting with is something that the work attempts to communicate. I can see it in the pictures, and the words are clear as well.

I suppose all of the above also must acknowledge the crucial fact that the final part of a biography — anyone’s, whether Levé’s or Sapienza’s — is always formed in a reader’s/viewer’s head: you respond to what you can and want to respond to. That’s the beauty of it all.

As I said, only a person who is more immersed in the world presented in the book can probably more fully appreciate and enjoy it. But that’s OK. In the end, with all pieces of art we’re limited in what we have available when facing them. The purpose of art cannot be to serve those fully in the know. Instead, art needs to reach out to those who are not.

That is what Iuzza does.

IUZZA. Goliarda Sapienza; photographs by Francesca Todde; texts by Luca Reffo; 280 pages; Départ Pour l’Image; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!