I’ve lost track of the number of photo festivals and photobook/photobook-dummy awards. Typically, these events come with shortlists. Often, these shortlists stretch the actual meaning of the word “short” quite a bit. For example, the Arles Book Awards 2024 “shortlist” contains 122 books in three categories. I became aware of this after stumbling across Instagram posts by publishers who “humbly” reported how three or four of their books had been listed.

It shouldn’t be necessary to explain how a shortlist of 122 books is ludicrous. Somewhere, I read that it was compiled from 800 books. But even if it had been compiled from 80,000 books, a list of 122 books is meaningless. It’s little more than an exercise to inflate 122 CVs (actually, since there are publishers and photographers and occasionally also writers, the number of inflated CVs is likely much larger).

It’s not even that mind seeing people rewarded for their achievements. That’s not the point at all. My point is that it’s not a reward to be on a list that has no discriminatory power. It is a lose-lose situation for everybody involved: the people who somehow don’t get shortlisted get to feel like real losers, given that so many of their peers were shortlisted. And the shortlisted photographers find themselves in some huge company.

I don’t mean to only single out Arles. That list is bad enough, but it’s hardly the only offender. Dummy Award 2024 recently announced that they had shortlisted 50 books out of 420 submissions.

With often very extensive shortlists and so many different shortlists, it sometimes feels as if every book has been shortlisted somewhere.

You can see exactly that effect with a number of photobook workshops that result in photographers producing dummies. Afterwards, the photographers flood all the various festivals with their dummies, inevitably some of them get shortlisted, and then the workshops advertise how beneficial the process is.

The larger problem is the following: the idea of awards for outstanding work has run its course. After all, while the number of shortlists (and “talent” listicles) has exploded, critical writing about photography has become rare. That can’t be a good development: instead of critical praise, people now mostly get semi-anonymous recognition in the form of being on a shortlist or — the lucky few — some award.

This development does not only apply to photobooks. You could say the same about Western (“World”) Press Photo (WPP), an award that every year reduces the (relative) complexity of photojournalistic work into some categories, each one with a winner. Inevitably, the overall winner then triggers the same conversation as the year before, which only proves that a) the makers behind WPP are either unwilling or unable to learn anything and b) in a world that is saturated with photographs picking one that satisfies a Western audience’s need to feel good about itself is absurd.

It would be straightforward to modify WPP to honour photographers and their work: simply don’t pick individual photographs. Award the photographers, and showcase their work. For example for this year’s winner, Mohammed Salem, the larger selection of his work around the carnage in Gaza would be much more challenging for an audience than that one single picture that sanitizes way too much and that too obviously caters to Western expectations.

After I posted a few very short words about “shortlists” on my own Instagram account (I had created a meme about the Arles shortlist earlier), I received some (private and public) comments. According to a number of people, the real problem is that there simply is too much of everything: too much photography, too many photographers, too many books.

Well, no. I will happily go on record as saying that I find that approach self-defeatist and extremely counter-productive. To begin with, I don’t see how it would be a good idea to go back to the world where there were a handful photobook publishers producing mostly books by wealthy white men (which is still happening, btw, those guys still churn out their stuff).

But the larger issue is that numbers never are a problem. The frequently used claims of “too many photographs” or “flood of photographs” are intellectually lazy and shallow. How would the supposedly large number of books be a problem when a much better approach would be to celebrate the medium for its sheer richness? Keep in mind that we’re now seeing a much broader range of work that previously would have had a hard time even finding an outlet.

Thus, the underlying problem is not that there are too many books (or too many pictures made or too many photographers). The underlying problem is a lack of interest or ability in dealing with the challenge in ways that do not simply and neatly replicate the casino capitalism we’re all embedded in: it’s all about winners and loser, and of course you have to pay money to be a part of it.

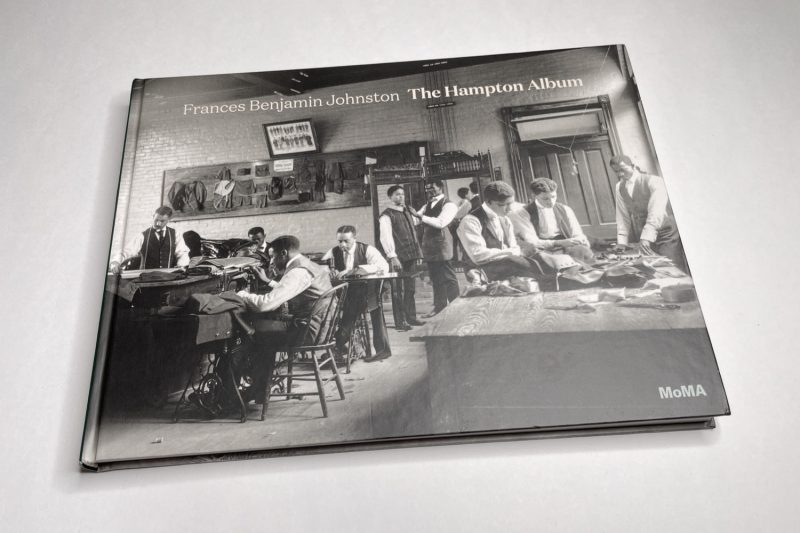

A photobook exhibition where you have dozens of books on tables, possibly with some added text, really is the bare minimum of what can — and I would argue should — be done with this particular medium. (In the following, I will stick with books, simply because it’s where most of my passion lies.)

Realistically, someone going to such a festival will browse through however many books their attention span and/or mental energy will them allow them to process. It takes time and energy to look at books. You simply do not advance careful looking at books by turning even the act of looking into a competition.

So what would one do if dumping a “shortlist” on an audience isn’t a good answer? Here are some ideas. You might have other ideas. In the following, I do not intend to argue that mine are the only possible ideas. I don’t even mean to argue that they’re good ideas. I simply want to point out some very basic deviations from a model that’s really, really bad.

The main reason why I’m suggesting something is that while a lot of people tend to agree with me when I point this stuff out, almost inevitably the question follows: “but what can we do instead?”. Well, maybe ask yourself first what you would like to see?

Anyway, to begin with, we collectively need to dump the idea of “the best”. I thought we had all agreed on being artists? Where is the idea of “the best” coming from? Yes, right, that’s just casino capitalism (and the internet — same thing, though). Chasing after “the best” and awards does not advance anything other than casino-capitalist ideas.

Finding the best books also is a bad idea because your idea of what’s good will likely differ from mine. If you think some book is good — and I do not, then what? We could either agree to disagree, but that would be a very sad baseline.

Ideally, we’d come to understand what we appreciate in each other’s choices, and we would both learn a little bit. We might still not see tremendous value in that other book, but we might be able to understand how someone else sees it. And that, in turn, will teach us something about ourselves.

I have some pointers for why some books might be a bit better than others, given how much time I have spent on writing about them, helping people make them, or making them. However, the situation in which you think a book is good and I do not simply is a reflection of our different personalities and expectations. And that’s perfectly fine. We need to move away from the rigid model of that very small select group of experts that get to decide what is good and what is not.

Picking “the best” precludes an approach of looking at books with differences between people in mind. Instead, it separates the 800 photographers into 122 (almost) winners and 678 losers. And it then pits the 122 photographers against each other, with everybody wondering which one (or which three, it’s three categories) will be “the best” (it might be the jury members’ friends’ — who knows?).

Instead, a jury should go through the 800 books and pick a small enough number in such a fashion that they can be put into a conversation with each other. Instead of a “shortlist”, you’d then simply have a selection of, say, 10 or 15 books (not more!). Those ten to 15 books would be presented by highlighting their connections — and differences.

Imagine walking into a room where instead of a competition between 122 books you have 15 books that each address a specific theme in their own ways. This would would trigger conversations around the books and between people — the exact opposite of the casino-capitalism outcome.

We need conversations around books and between people more than ever, given how increasingly fractured our social and political spaces are.

You might imagine that this approach would be similar to those shortlists produced by prizes around some incredibly vague and ideally completely inoffensive theme. But no, to create something of value, you need to do better, something that has some bite.

You want to aim for intelligent conversations that elevate the books and their makers — and not plaster over differences by making everybody feel good about themselves.

Consequently, the jury would really have to do some work. I’m imagining that there are people out there who have the competence, passion, and energy to create something smarter out of 800 books than a “best of”.

The key would be to create something intelligent, something that will get an audience engaged and that helps them understand the books and the art behind making them better.

As a consequence, book presentations have to become a lot more engaging than they currently are. Books on tables do not invite cross-conversations. They merely invite solitary looking. If there are books on tables, efforts have to be made for viewers to engage with each other.

What prevents you from having a small room where someone will present a book to a small enough audience that a real back and forth would be possible? What if there were eight different artists, curators, writers every day who present and discuss one book of their choice during the eight hours of the day? The possibilities are endless.

Photobooks are typically made by incredibly passionate people, and they’re discussed and viewed by equally passionate people. Why wouldn’t you tap into that passion as the organizer of a festival? It boggles the mind!

In the end, though, it can’t be only on the organizers of the festival and the juries. If enough people are unhappy about our casino-capitalist world of photobooks, then we have to make the decision whether we want to do something about it or not. We can either put ourselves at the mercy of what people offer — or create something ourselves.

Remember that, for example, Aperture magazine was founded by Ansel Adams, Melton Ferris, Dorothea Lange, Ernest Louie, Barbara Morgan, Beaumont Newhall, Nancy Newhall, Dody Warren, and Minor White. What is preventing photographers today from launching a new magazine? What is preventing photographers from starting their own festivals?

Please don’t tell me “there’s no money”. I understand that money is a problem. But why couldn’t a photo festival be a collection of connected open-studio situations with, possibly, some other spaces added in?

I’m genuinely puzzled by the general lack of imagination. So many people are so passionate about photography. Creating art relies on creativity and on making do with what you have. What’s preventing people from applying those skills when it comes to creating cross-conversations around their photographs and/or photobooks?

OK, I get it, as a photographer/artist, life is busy enough. Maybe you’re even an academic and have to waste your time with the energy vampires in academia.

Still, things aren’t going to get better if there aren’t efforts made to change something. Because honestly, unless some people get together to create something better, we’ll be stuck with casino-capitalism festivals and “shortlists” for which even a CVS receipt is not long enough.