I have long been baffled by the fact that if you want to learn more about photography, arguably the most important medium of our troubled times, you’re made to face a library of writing that is neither wide nor deep. In fact, that there is indeed useful writing around photography is almost accidental. None of the people who wrote the most widely read texts were photographers (or curators). Roland Barthes was a literary theorist, Susan Sontag was writer, and Walter Benjamin was a cultural critic.

Possibly, this all makes sense, because on its own, photography is entirely without meaning. Of course, you can make photography around photography and then present the results in the context of art museums or commercial galleries. But no insight whatsoever is gained from writing that attempts to make sense around such endeavours — other than navel gazing or (this is not a given) insight into the machinations of the institutions that produce such exhibitions.

Thus, we have to look for insight into what photography is — and this inevitably means what it does and how it is being used — elsewhere, outside of the narrow confines of photoland. And we can only hope to get to a closer understanding of the medium if we look at it in context — whatever that context might be. As is the case with photography itself, something will have to be at stake: there will have to be some tension, some hurt, for true insight to be gained.

If the author (or photographer) does not feel such tension or hurt, it’s very unlikely that a reader (or viewer) will. The reader might have experiences with the same tension or hurt; or she might not. It’s the sign of good art being present that even if a reader is unfamiliar with the world presented in a book, they will still be able to connect to it and, at the very least, understand that beyond their own world there is a larger one, in which things unfold in entirely different ways.

What makes photography so potent is that it has the potential to short circuit critical thinking. Photography triggers our best and our worst impulses, leaving us at the mercy of our own unfinished and imperfect selves. Contrary to what we might be inclined to believe, we have to do the work when we see a photograph. It is convenient to attempt to offload the blame onto the photographer. However, even where such an approach is justified (it might be, but usually is not) that doesn’t absolve us completely from facing the truth we perceive in a photograph.

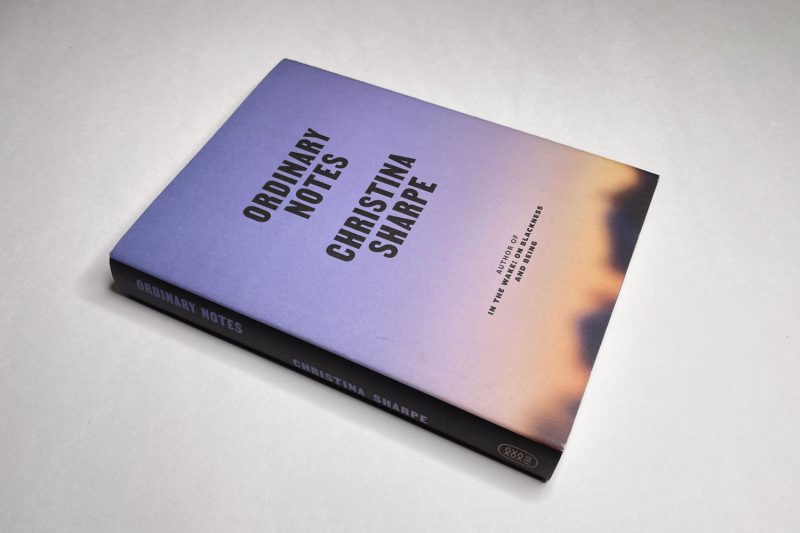

Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes is not about photography. The book’s focus is Blackness and its position in a world that is structured around racism. But — maybe I should write of course — photography plays a part in it, because the medium has been used for exactly the purposes from which the author now has to extricate herself.

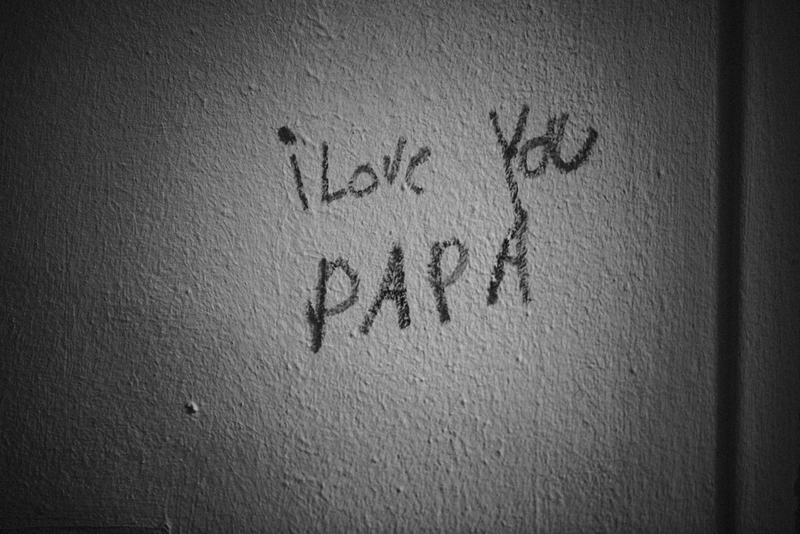

Photography has always been used to define (and thus to reduce), and it is exactly the struggle to break from and against definitions set by white people that most of Sharpe’s 248 Notes center on. But there is a lot more, in particular love and care; in her final Note, the author writes “This is a love letter to my mother.”

Ordinary Notes is one of the rare books where once I had finished reading it, I immediately thought that I needed to read it again. There is a wealth of material inside, some of which I connected to easily (for example the photography parts), some of which was harder, given my own lack of exposure.

Of course, there is the basic fact that even though I have been living in the US for a quarter of a century now, for me as a white German man, larger parts of my adopted home country are still profoundly strange and unknown to me. While I’ve given up on some (I will never understand the appeal of baseball, say), I’m still attempting to understand many others.

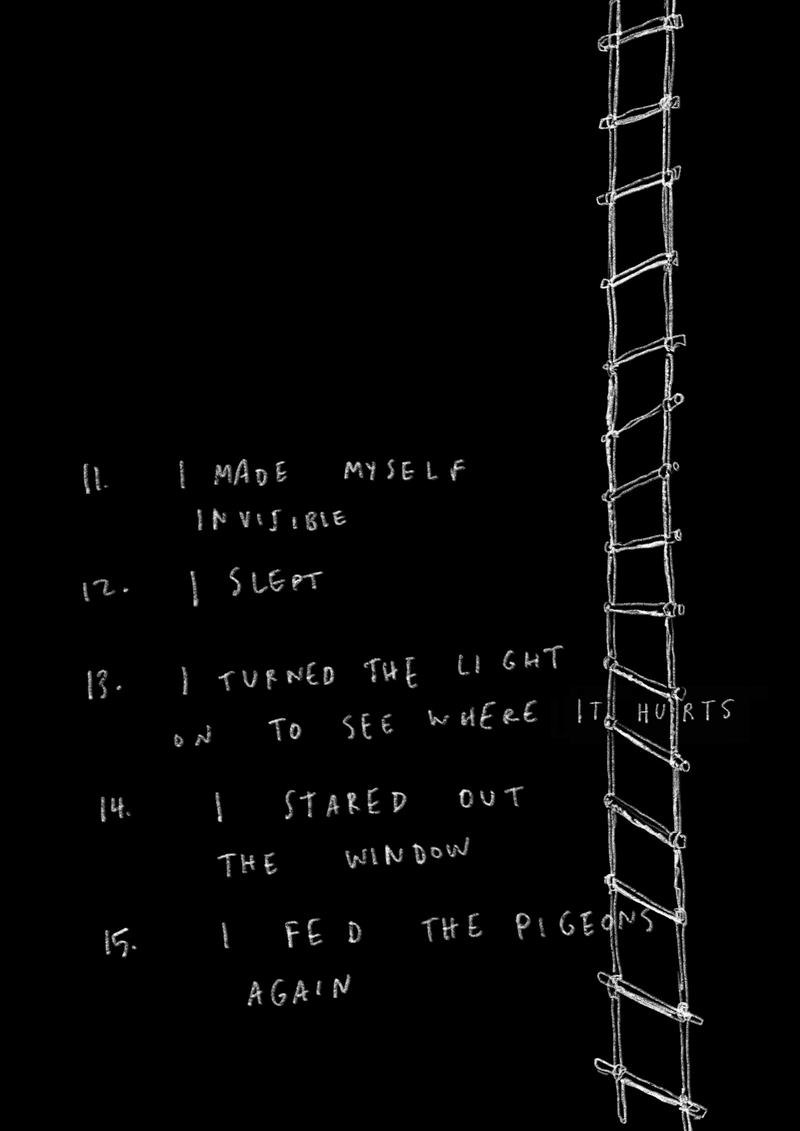

But that’s the beauty of books: if you keep them in your house, you can come back to them, so that they can teach you something new. In Ordinary Notes, Toni Morrison’s Beloved is one of the books that is given that role. Notes 207 and 211 show photographs of Sharpe’s copy, which is filled with added sticky notes and writing. Unlike your friends, books will allow them to do this for you.

In the context of Ordinary Notes it’s not the novels that strike the most contemporary note, and certainly it’s not the photographs. It’s the videos that, I suspect, we all have seen or made to see, or maybe we decided not to watch them: the videos made by people present when cops murdered Black people, most famously the video of George Floyd’s death, which led to an eruption of mass protests a few years ago.

Photographs do their thing, novels do their thing, videos do their thing — when you want to find out how different media work, you typically learn the most by looking at a collection of them in a specific context. Sharpe deftly weaves in and out of all of the different media, while approaching them from different angles.

A comparison with Barthes’ Camera Lucida is most instructive, given that for both authors photographs of their mothers are of central importance. Where the French writer never actually gets close to his own feelings, Sharpe centers herself right there. The reader gets to see the pictures in question (compare that with Barthes’ “Winter Garden” picture being absent), and the looking is a careful look and untangling of what, in effect, cannot be untangled.

“With beauty,” Sharpe writes (in Note 138), “something is always at stake.” This observation follows a longer quote by Glenn Ligon who noted that “discussion around beauty is often used as a way to preempt any debates about exclusion or marginality or privilege or any of the topics that had some currency in the art world of the late eighties and early nineties.” With my own students in the past, I was unable to have discussions around beauty: they wouldn’t consider it. It was as if the idea of beauty was somehow tainted.

Or maybe it was simply that they realized that something would be at stake.

If I were still teaching photography, Ordinary Notes would be the first book I would ask my students to read. As I tried to describe above, if there is a way to discuss photography, it ought to be done in context, looking at how photographs are used and how they operate in context. Furthermore, unlike many of those who wrote about photographs, Christina Sharpe does some very careful looking (at some stage in the book, she fillets Barthes over his careless looking and writing).

But of course, the book concerns itself first and foremost with Blackness and with being Black in a structurally racist world. If, as is being made very clear in the book, Black people have to engage in very careful looking in order to be able to live their lives as unharmed as is possible (as the videos of the police murders demonstrate, some things cannot be controlled: “the always-present threat of state violence against Black people” [Note 231]), then that very careful looking also has to happen by those who live with the luxury of not having to do it.

If people are happy to pledge “liberty and justice for all”, then that ought to have consequences. Justice is not justice if it is only justice for some. Liberty is not liberty if it is only liberty for some.

“I want acts and accounts of care as shared and distributed risk,” Sharpe writes (Note 234), “as mass refusals of the unbearable life, as total rejections of the dead future.”

Highly recommended.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!