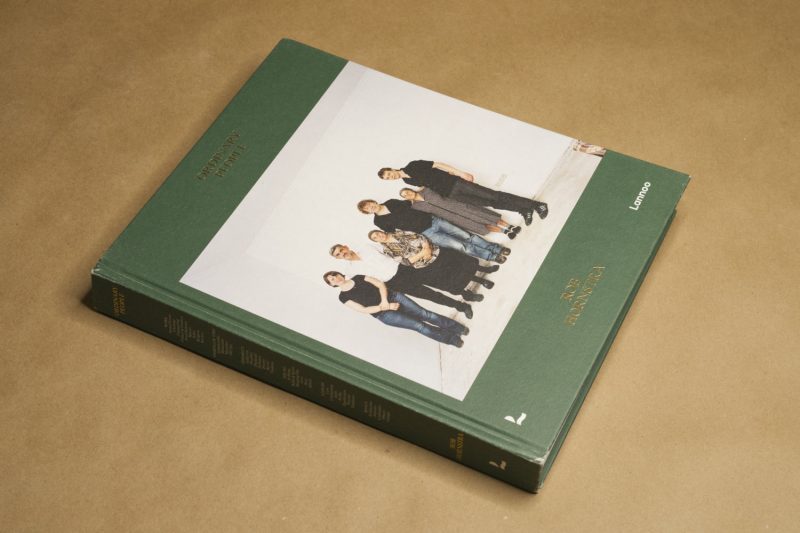

Ordinary People, the catalogue produced at the occasion of Rob Hornstra‘s mid-career retrospective at Fotomuseum Den Haag, might feature the most atypical cover photograph. It’s slightly wonky, and it has six people pose who, this much is clear, ordinarily do not assemble in this fashion.

At the right-hand side of the group, there is a boyish looking man whose body posture betrays being tall and thus having to more or less constantly accommodate to people of more regular height. That’s Rob. There is another interloper, a man with curly hair. That’s Arnold van Bruggen, a writer and Rob’s artistic partner. Together, they have been producing some of the smartest contemporary documentary photography over the past two decades.

In many ways, presenting just Rob’s work — the pictures — without Arnold’s words is strange. Originally, I had a hard time imagining what that might look like. The title of the book (and exhibition) gives away the device used to tie together the work made in various European countries and in russia: Rob’s interest is in ordinary people.

Of course, that idea provides one of the major threads of photography’s history. Photographers love looking for ordinary people, because that way, they can — at least that;s one of art photography’s talking points — give them visibility. Richard Avedon, for example, trekked all across the American West to do this.

The reality is that Rob’s pictures have very little to do with Avedon’s crass and lurid spectacle of underprivileged strangers. For Avedon, his subjects were devices to produce pictures for his wealthy patrons: means to an end. Rob, in contrast, is genuinely interested in how the people live who end up in front of his camera. If you don’t believe it, read the text in the books that usually contain them (I reviewed many of them on this site; you can find the articles in the Archives).

The catalogue itself also makes Rob’s case. Inside, the many different locale’s are intermingled. It might have been tempting (and oh-so boring) to produce some sort of time line, with pictures made for different projects being kept strictly separated. Instead, with the help of some categories (Work, Disparity, Young, etc), photographs from different contexts are being put into new ones. And this works.

In between, you get all kinds of extra goodies: essays, presentations of outtakes, background information provided by Rob, some of the stories around the making of pictures (with, obviously, the most frightening coming from the hell hole that is russia); as always, designers Kummer and Herrman gave this all an elegant and attractive form. Rob also compiled and condensed the various interviews I did with him for the book.

What’s interesting about the book is that as the narratives from the original projects fall away, the pictures still hold up. But they do it differently than when accompanied by text. Where in the case of text next to a portrait, the text fills in a lot of what the picture is unable to show, here it’s the presence of the other pictures that does the lifting.

I wouldn’t want to say that as a viewer you compare; but for sure what initially comes across as some sort of obvious organization (the categories) ends up bringing together shared sensibilities between those portrayed. This is, after all, what you can do with photographs: their meanings are not tied down, and there is much to be gained from showing the same photographs in different contexts and configurations.

Still, with the russians portrayed in the book, I couldn’t help but wonder how many of them, especially the younger ones, have by now become cannon fodder in Vladimir Putin’s genocidal war in Ukraine. For example, the young boy on page 13, photographed in an orphanage in Chelyabinsk in 2003 — two decades later, he would be of the right age to be a part of russia’s murderous war. Or maybe he now lives abroad, having fled like so many others?

If anything, the fact that brutality is often only one step away in regular human life provides one of the mostly hidden threads in the book — where it doesn’t present itself in all of its gory nastiness, such as when a group of butchers pose in front of the carcasses of animals they have killed.

Thomas Hobbes argued that without government, life would be solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. Well, with government it is the same for many people, especially if they’re of the ordinary kind.

It’s difficult to imagine the sheer amount of work then went into this mid-career retrospective. “Talent is insignificant,” James Baldwin said, “beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but, most of all, endurance.”

If anything, Ordinary People is testament to exactly that: a photographer’s absolutely incredible discipline and endurance, and his love for those whom he asked to pose in front of his camera.

Highly recommended.

Ordinary People; photographs by Rob Hornstra; essays and words by Lynn Berger, Willemijn van der Zwaan, Arnold van Bruggen, Rob Horrnstra; 320 pages; Lannoo Publishers; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!