Swedish photographer Gerry Johansson is widely known for his mastery of the square format. His square pictures typically cover some geographic region, ranging from countries to towns. They each are perfectly composed, combining extreme formal accuracy with incredible photographic wit. Many of the books with these photographs are simply organized alphabetically, with locale A coming before locale B etc.

But how did Johansson arrive there? Where is all of this coming from? For those curious, the answer is now provided in Coast to Coast, a publication that features photographs taken in the 1980s with a biographical text by the photographer himself. It would seem that the book came with a set of ten prints. However, a quick internet search tells me that it can also be bought separately from a number of booksellers (here’s an example).

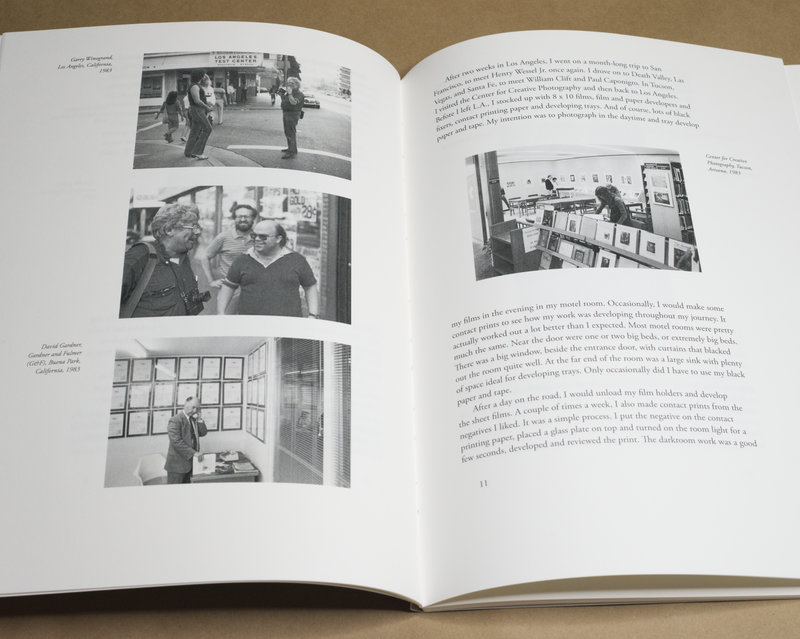

I suspect that those interested in the history of American photography will have a field day with the narration in the book. Johansson discusses a number of visits to the US, starting with one in the early 1960s. During the following ones, he got in touch with and met a number of well-known photographers, including Garry Winogrand, Henry Wessel jr., Richard Benson, and others. Coast to Coast has receipts in the form of photographs taken at these encounters.

For me, the more interesting aspect was to read about the photographic work, even as I appreciated learning about the education (if you want to call it that) Johansson received. In 1983, the photographer set out on a cross-country road trip. Staying at motels, he would photograph during the day — with an 8×10 camera — and develop and print the results at night. “It was a simple process,” he writes, “I put the negative on the contact printing paper, placed a glass plate on top and turned on the room light for a good few seconds, developed and reviewed the print.”

If anything, it’s the sheer discipline that delivered the results — and that is, of course, the one lesson for photographers (or writers or anyone else): “Talent,” to quote the late, great James Baldwin, “is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but most of all, endurance.”

Motel Prints is possibly too modest a title for the photographs in Coast to Coast. Whether or not these pictures are reproductions of the original motel prints isn’t clear to me. Based on the text — “The prints were by no means great, but good enough to view.” — I’m thinking they are not. In any case, the analogue silver-gelatin prints have been translated into pictures produced with ink on paper. And I really don’t want to geek out on print quality here, because that would take away from the essence of these photographs.

In obvious ways, the pictures show someone from outside the US finding visual attractions to take photographs of. By 1983, Johansson clearly had done a lot of looking at other people’s photographs to produce the occasional homage, whether to Walker Evans or anyone else. Those pictures are good.

But it’s the other pictures that are a lot more interesting, the photographs that speak of Johansson’s own unique mind. In essence, they are versions of the square photographs he is so well known for, with the frame extended by the 8×10 aspect ratio. As can be expected, every single picture is perfectly composed. A view camera will make you do that if you pay enough attention; and I wager that Johansson’s training as a graphic designer contributed its part.

I have attempted to describe what makes Gerry Johansson’s photography so exciting to me before. I’m not sure whether I have succeeded — I’m thinking I have not. Maybe it’s simply the fact that the visual wit appears to have done for nothing other than its own sake.

In other words, the mastery behind all of these photographs is only the tool it should be, a tool that, of course, has to be fully controlled. But I have never had the slightest impression that any of Johansson’s photographs wanted me to consider anything other than themselves: a way of looking at an often mundane world that brings out little glimmers of intense joy, even when you’re finding yourself in the most dreadful of visual circumstances.

That’s really the essence of this photographer. The world isn’t beautiful per se. The world simply exists, and it couldn’t care one bit about what we think about it. It’s up to us to view this world any which way we want (or are able to — those two aren’t necessarily the same). If you make the decision to find beauty in the world, then you can. One way, Johansson’s, is to embrace the idea that whatever beauty there is, it’s ours, the one we construct.

Every photograph by Gerry Johansson is a reminder that beauty, enjoyment, and contentment are entities in our minds. It is up to use to recognize and embrace this basic fact. And the key isn’t even so much to take photographs as proof — most of us will fail to reproduce this artist’s pictures (and what point would there be in trying to copy them anyway?). Whatever tool helps you get to a more content engagement with the world — whether a camera, a pen, even just a spot to sit down to look — will do.

Coast to Coast; photographs and text by Gerry Johansson; 48 pages; Imagebeeld Edition; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!