[From 2019 until early 2023, I spent time writing a book about fathers and sons and how fraught father-son relationships can be seen and read in a number of well-known photographers’ works (incl. Larry Sultan, Masahisa Fukase, and others). It was for that reason that I was interested in Bharat Sikka’s The Sapper. After spending a few months on trying to find a publisher for my book, I’ve come to the conclusion that it will probably remain unpublished. Should I end up being mistaken, the following might make more sense — or maybe it will finds its place in a much wider context.]

Men have to learn what it means to be a man, meaning: how to engage with the world around them. For better or worse (and it often is the latter), it’s other men doing the teaching, with fathers being the first male role model for a boy in a traditional family setting.

Conservatives and other people further to the right insist that it’s the traditional family — husband plus wife plus child(ren) — that guarantees a healthy society. You only have to look around, though, to realize to what extent this idea is complete nonsense. It’s traditional families that are the breeding grounds for toxic masculinity, with a father who might have never learned anything about vulnerability or empathy from his own father now instilling these own ideas in his son(s). Inevitably, in his teenage years a son will at least temporarily stage a protest against his father, which only helps to inflame the seeds of toxic masculinity.

And so the cycle continues throughout the generations, producing emotionally crippled men who subject those around them to the “lessons” they learned, meaning: inflicting emotional and/or physical violence on their immediate families while on a societal scale perpetuating the nasty system of patriarchy.

It is against this background that a photographer taking pictures of his father has to be seen. The act of photographing differs a lot from when the same photographer approaches a stranger to take their picture. The title of Bharat Sikka‘s book, The Sapper, is apt: more often than not, the ground between a father and a son is a minefield. One wrong step and — boom! — something will go off, causing great hurt to at least one of the parties (and possibly also to familial bystanders).

Of course, Sikka’s father was an actual sapper in the Indian army. I don’t know to what extent the metaphor might have played a role when the book’s title was chosen. As in all the other cases where photographer sons took pictures of their fathers, there have been careful negotiations over their taking (if you look carefully, you’ll see that all those well-known supposed family books are essentially centered on the fathers).

As viewers, we have no access to these negotiations (unless people like Larry Sultan tell us, in which case we still have to remain vigilant, given the son’s hidden agenda). But we see the outcome, and we can come to educated conclusions about what the negotiations might have been. In The Sapper, we see an older man who appears happy to play along and who submits to the staging of a fair number of photographs. Whose idea the staging might have been, we don’t know. It actually doesn’t matter. What should concern us is the spirit conveyed by the pictures.

The staged portraits of the father are matched by a large number of other photographs that show carefully constructed scenes, such as for example a pile of chairs. Occasionally, there is more than a single photograph of a staged scene, with the stages of construction being evident in the individual pictures. Even as there are many “straight” pictures in the book, in particular landscapes, these are less prominent than they could be, given the rather heavy hand involved in the staging of the other pictures.

Looking through The Sapper, I ended up feeling that I was really meant to take away something very specific from the work. Obviously, that’s the case for any photobook. But here, the cumulative effect of the staged photographs left a heavy mark, too heavy a mark at times.

For example, late in the book, there are images of photographs seen earlier in the book, now displayed in wooden frames. I get it, parts of contemporary photography enjoy celebrating their own cerebral — if often rather simplistic — photographic wit. But I wonder to what extent a relationship between any two people, let alone the one between a father and a son, is served by dumping art-academy artifice over it?

Well, then again, the book isn’t the relationship — that’s between the father and the son. Much like his predecessors, Bharat Sikka invites us to see one — the book — as a reflection of the other — the relationship. And it’s tempting to buy into that. But as viewers, we might as well remind ourselves that the photobook, any photobook really, is its own artifice.

“This is a story of companionship,” Charlotte Cotton writes in the afterword, “where neither the patriarch nor the artist command superiority over the other.” Not so! Not so at all! Just like in the case of, say, Larry Sultan, the artist-son very clearly commands superiority in any number of choices made here, which includes the end product as much as the decisions that went into the making of all the various pictures.

I desperately want to believe that the relationship between this particular father and this particular son does not at all follow the outline in the book, one where crafty artifice sets the dominant tone.

But that might well be the case.

I have no way of knowing.

[Absent the text I wrote being available, I can’t go any further with this piece. I could add more, but it would not make sense for a reader who can’t know where it’s coming from. In any case, with the above I don’t mean to imply that this is a bad book — far from it. It’s a good book. And it contains a lot of good photographs, even if the edit could have been tighter. But as the flawed son of a flawed father (or rather simply as the son of a father) it shudders me to think that a viewer might infer more about a father-son relationship from it than what is communicated by the pictures and their staging.]

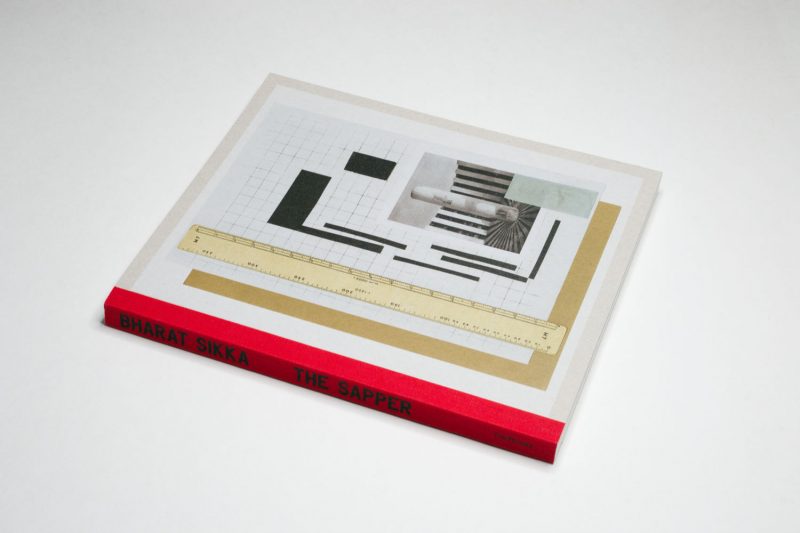

The Sapper; photographs by Bharat Sikka; essay by Charlotte Cotton; 192 pages; FW:Books; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!