When I received Anne Morgenstern‘s 2015 book Land Ohne Mitte in the mail, I knew immediately that it was a landmark publication. The book looks deeply into something that in the immediate next years would explode out into the open in Germany, first with Pegida and then with the far-right AfD, a party that would openly establish racist and neo-fascist discourse in Germany.

It’s too easy and simple to tie all pf this to the East German states. After all, West Germany had had its fair share of far-right extremists. Before the AfD, those had mostly been bound to other far-right parties but had also had representation in the nationalist wings of the main conservative parties (to some extent, the latter is still true today).

Given its history, though, there was something different going on in East Germany, something that I had a hard time understanding, given my own biography as someone born in the West. Anne’s book pried something open, and it helped me see things less black and white. A little later, Anne produced Reinheit, another book that centered on something very specifically German.

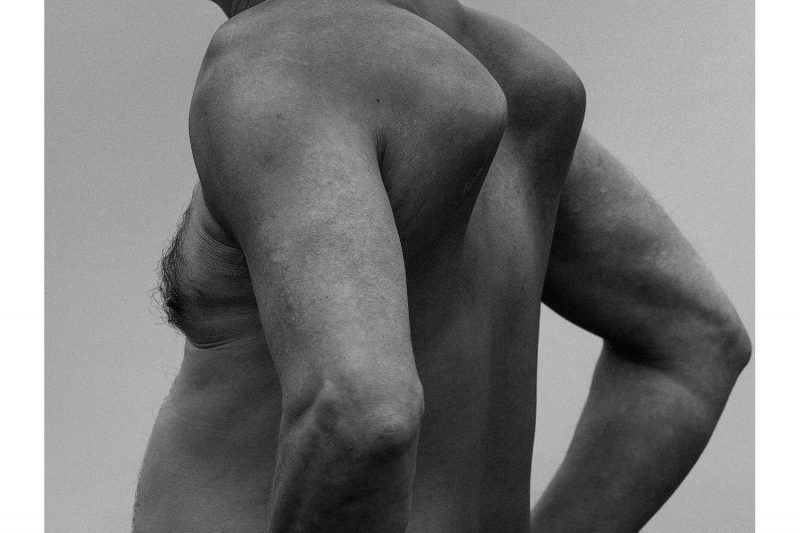

What’s striking about Anne’s work is her ability to convey things using an imagery that is, for a lack of a better description, visually endearing first — before it cuts to the chase. This approach might confuse non-Germans and Germans alike, given that photography made in Germany often (but not always) is very cerebral, at best keeping things at arm’s length. It’s not that Germans have no emotions, but they don’t tend to wear them on their sleeves. For better or worse, much of Germany’s photography reflects this approach.

Given the preceding and given my interest in German photographers dealing with their country’s hugely problematic history, I had wanted to speak with Anne about her work and about what it meant to her. For my ongoing series of conversations about Germany, I reached out to her, and much to my delight, she was happy to chat. For this conversation, I spoke with Anne over Zoom at the end of November this year. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity, and it was translated from its original German.

Jörg Colberg

You were born in 1976 in Leipzig. So you experienced quite a bit of the GDR?

Anne Morgenstern

Yes, and I think it had a big impact on me. I’ve read a lot about it later. It’s very interesting to realize that it’s not just me, but that quite a lot of things and sensitivities that shape me are partly a historical phenomenon.

JC

I find that very interesting because I grew up in West Germany. I have the imprint of the “other side”. How would you say that it shaped you? How would you describe that?

AM

I have to tell you a little bit about my biography. It’s pretty rough. When the Wall came down… Actually, I have to start a little earlier. The year 1989 was a really dense affair.

My grandmother, my father’s mother, was a senior lecturer in German and journalism. She had an old apartment. Since there was a housing shortage in the East, my parents moved in with her. The four of us lived in the apartment, which wasn’t always easy, especially for my parents.

In the fall of 89, I was 13 and the Monday demonstrations were in full swing. The mood was very charged. In my family, too. My mother always wanted to go to the West and probably would have gone without my father. Then, three weeks before the fall of the Wall, my father took his own life. From today’s perspective, I would say that my father was severely depressed. He slept a lot, he was very withdrawn, and as a person he was always somehow absent. I assume that the fear of change, the fear of the unknown was the trigger for his suicide.

I later realized that my father also was a person of his generation in the GDR. There were many depressed people who were not allowed to be depressed. There were an inordinate number of suicides, but you were not allowed to call them that. It was the same in my family. You weren’t allowed talk about it. “You don’t do that.” Therefore, I had to come up with something that happened to my father.

Then the Wende happened. When the Wall came down, my mother applied to leave the country. In February 90, she immediately moved with me to Munich because her sister lived there. My aunt had left for the West when she was 19, before the Wall had been built. She was seven years older than my mother. That’s why we ended up in Munich. As I said, I was 13 years old. I think that’s really a difficult age.

Later, I read a very good book by Steffen Mau, Lütten Klein. As someone born in 1968, the author himself grew up in Lütten Klein, a prefabricated-housing estate near Rostock. He is a micro-sociologist and can describe these phenomena extremely well. That was an incredible eye-opener for me. My generation is called Wende-Kinder [children of the Wende]. These are people who were born in the GDR between 1975 and 85 and whose parents were completely overwhelmed and marked by existential fears.

The parents were born between 1940 and 1960, had lived in the GDR for too long and were so firmly rooted in it. They were no longer young enough or already too established to be able to go through the tour de force of having to redefine themselves. The Wende-Kinder are a generation of people “lacking guidance”. That’s how Mau describes it. Everything changed 180 degrees. Teachers no longer had any authority. And the parents were, as I said, totally overwhelmed. In some cases, children had to assume the position of adults. Adults didn’t provide any guidance. This is similar to what happened to me.

My mother was very cool. But she was a woman of her time from the GDR: independent, emancipated, in a practical, everyday sense. She left without a man. That is a phenomenon that was typical of the GDR. The migration movement from the East to the West was dominated by women. In some areas, more than two-thirds of the women went to the West, and the men stayed behind. Women were used to having jobs, earning their own money. They were more flexible and pragmatic. That’s why they were much better off in the West, especially in the service sector — unlike the male labor heroes who stayed behind.

And then I had this hard impact in Munich: to feel what it means to be an Ossi. I thought that that was the ultimate crash.

JC

What was that like for you at that age? I remember when I was 13 years old that was a weird time.

AM

It was really terrible.

JC

I’m trying to imagine having to move at that age into a completely different environment… And Munich of all places. I’m from the north and lived in Munich for a while. I hated it.

AM

Munich is still okay. I moved to the affluent suburbs because my aunt lived there. I don’t know why my mother did that. She never suffered from it and always thought it was a bit cool. I thought it was terrible. Even today, when I go to those suburbs, I feel paralysed and suffocated. That’s what I was trying to work through with Reinheit, the tightness that surrounds me there. It was such a double whammy, Munich and Ossi. Munich is difficult anyway. [laughs] Add to that being East German… That was something totally new for me.

Up to that point, I had had a very nice childhood and a great youth despite my absent father. And lots of girlfriends. That was really beautiful. It actually hurt me to leave, even though there was the promise of the West. When I arrived there, I thought “What? That’s it? That can’t be what everyone was talking about.” Bavarians and Westerners can be very… Well, it’s probably the Bavarians, because I didn’t know the others. But to be burdened with being inferior — that was quite corrosive, also from the teachers’ side. At times, that was rather tough.

JC

I lived in Munich myself, and even as a West German I found it very restricted and narrow minded. I imagine it’s very difficult to be an East German there.

When the Wende came, I had just gone to university. I had lived at home for a very long time, I was dependent on my parents. For the first time, I got out to study physics.

AM

When were you born?

JC

1968

AM

Ah, so you’re another one from 68.

JC

Yes. I got out and studied in Bonn, the capital of West Germany. That’s when I had to stand on my own two feet for the first time. The fall of the Wall and reunification — with all the upheavals in my personal life, I didn’t really notice it so much. But I noticed that I was unable to place people in East Germany.

Two years before I graduated from high school, my class went on a trip to the GDR, to Dresden and Postdam.

AM

The real GDR experience?

JC

Yes. That had been the only opportunity I had had to meet people from the GDR. The FDJ had a lot of control over whom you would meet. There was a youth evening where selected GDR youths hung out with us. It was just like you’d imagine it from West German anti-GDR television programs.

AM

I am a little bit envious. If I could time through travel, I would definitely go there, but as an older me.

JC

Right, that’s what I always think. I often think about it, even if it doesn’t make sense. I really wish that at the time in Bonn or during the trip to the GDR… I wish I had had the knowledge I have now.

AM

Absolutely! I agree completely.

JC

That is such a missed opportunity for me, not dealing more closely with the Wende. At the time, I was very actively looking into West Germany’s Nazi past and asked around in my family, “What happened then?” All those stories you heard — nobody knew anything, and there had been so few people who had actively participated… I simple didn’t believe that. That just couldn’t be correct.

AM

I don’t believe that, either.

JC

Over time, the truth emerged. So I looked into German history. On the other hand, though, I was busy with petty personal problems and practically missed German history unfold in real time.

I can’t imagine being thrown into a completely different world at a time like that. That world is not so different in itself, because there are also Germans. But at the same time, it is totally different.

How did you find the topic that became Land ohne Mitte? Where did you study?

AM

I studied in Munich at the Staatliche Fachakademie für Foto-Design (State Academy for Photo Design), and then in Zürich at the ZHdK (Züricher Hochschule der Künste — Zurich University of the Arts).

I read the interview with Jonas Feige. He says that he has always been interested in history. I am a person who always tried to pay attention in history classes. But I had very bad history teachers. I never understood the larger context.

Something I always have to do if I don’t understand something is to look at it from the inside. I knew Michael Schmidt a little bit. He pushed me and told me [Michael Schmidt voice:] “You have to work on something that has something to do with you!” So I started taking pictures of some of my girlfriends. That was very pretty lame.

Why did I then go back to the East… After the birth of my son, I had an endless longing a) to get away again and b) for these places. The sociological moment that resulted from it came later. In the beginning, I had a longing for landscapes in the East. I chose Knappensee. I didn’t want to go to Leipzig because it’s a city. It had changed very quickly. The city of my childhood had disappeared extremely quickly.

That’s another aspect of me being a child of my time. Having to deal with it again and again – that always comes back. Also the longing for it. The visuals — the symbols, the pictures, but also one’s biography — that was not accepted. It wasn’t valued either. I had a longing for big trees and trails and lush, strangely overgrown hedges.

So I went to Knappensee, which is in Upper Lusatia. I researched it a little bit. The area is a conglomeration of my mother and my grandmother. My mother used to work as an engineer, industrial hygiene. Se took measurements in lignite-fired power plants to see how much of a health risk they posed. She also did asbestos measurements.

My grandmother was a Germanist. There were letters between her and Brigitte Reimann, a writer. Reimann wrote a lot about everyday working life in the GDR. She also wrote about an architect, “Franziska Linkerhand,” who was involved in designing a new city and was critical of it. For a while, Reimann lived in Hoyerswerda. She went to these places especially to be able to write from there, from the inside. That’s why I went there. There was something for me.

The first time I went to Upper Lusatia with my mother, who was babysitting my son. I kept walking around the lake. The lake is in the book. It comes up again and again. At some point I realized that that wasn’t enough. [laughs] I printed out the pictures that offered something, put them on the floor, and asked myself “what’s missing?”

I realized that I might have to go to Hoyerswerda after all. At first I wanted to avoid it, because for me it was associated with the events of 1991. But then I went anyway. I started to meet people there, at parties, in pubs, etc. Before I did that, there was no tension at work.

When I work on photographs, I always need something that attracts me very much and that repels me at the same time, something that is a bit unwieldy — full of love and yet raw. That’s where I was digging: where do I find this unwieldy material?

JC

With Hoyerswerda, you picked something really unwieldy.

AM

It’s unwieldy, but also not so unwieldy. I also have a very loving attitude towards it. I can see myself very much in it. And I accept that, I think, also the people. But of course I exclude the radical right-wing scene from that.

JC

Perhaps my reaction is simply based on how I perceived Hoyerswerda at the time. I read newspapers and Der Spiegel, and I learned about the big news items while I was busy studying physics. Hoyerswerda was one of the big topics where I was just shocked. I remember that. I asked myself how it was possible that something like that was back, that something like that was happening again in Germany. I don’t remember if it was the first pogrom…

AM

It was the first pogrom.

JC

Now, I know how little I understood at the time about what was going on in the East. Looking back, I regret that I didn’t go there to deal with it myself. To meet people and so on. But I remember how shocked I was. And that’s why this is a huge issue for me. I’ve also been dealing with the subject in my own work: the far-right movement in Germany. That’s why I find it so impressive that you have dealt with it. But with your socialization and your background, you probably see the topic differently.

AM

Yes, I have always tried not to treat this particular aspect as the main part. It is one aspect of many, and it shines through. In my work, I’m fundamentally interested in approaching it without prejudice: To look for the places, to try to understand. I try to understand what is going on or what is present not with my head but with my heart.

Do you know the Thomas Heise’s films? He produced many documentaries in the East, Stau – Jetzt geht’s los and Kinder. Wie die Zeit vergeht. He did a lot of interviews. He did these in 1990, 91, 92, and then again in 2007 in Halle Neustadt. In the past, they were always impossible to find. But now they are available from the Bundesamt für politische Bildung (Federal Office for Political Education). I can highly recommend them. Among other things, there are interviews with 18, 19, 20-year-olds from the right-wing scene. They are very interesting.

Steffen Mau takes a completely different approach in his book. Unfortunately, it was not yet available when I did my work. He describes how the emigration of women and the fact that men stayed behind created a strongly male-dominated society in the East. Between 1991 and 2005, in some cases two-thirds of the women left for the West, excluding Leipzig and Berlin. That is the first point.

The second point is that there was a very striking drop in the birth rate at the time of the Wende. Normally, something like that would have been in the single digits. But due to the combination of these two facts, there really were years in which there were 300 men for every 100 women.

Mau dives deeper into it. Women tend to marry men that are socially better off. Consequently, there was such a blatant asymmetry between men and women that the classic working man ended up remaining single. There is the theory that men in male-surplus societies tend to be much more violent and that testosterone levels of men who are not in relationships are much higher. So they have to assert themselves through much more aggressive, physical behavior. That’s how Mau attempts to describe it.

On top of that, of course you have the issue of self-esteem, of not being seen, the fact that one’s descent, which has so much to do with identity, was never recognized. When you’re from the East, this wound always returns. It’s soooo deep. That’s really crazy. Of course, the AfD is heavily exploiting this, including with sentiments such as “now they’re also taking away our women.”

JC

That’s consistent with what you see with neo-fascism here in the U.S. A lot of it runs on the idea of masculinity. A perceived loss of power, a loss of recognition. People are suffering from that — whether they’ve lost their jobs in the Rust Belt or they don’t have jobs. I think the U.S. is even more conservative than Germany in that regard. The image of the man, the masculine, is still much more pronounced here than in Germany. That’s where it gets charged, probably to a similar extent as in East Germany, only against a different background. Masculinity is seen as under threat. The right-wing right offers a way out with a constructed identity.

You now live in Switzerland. How long have you been there?

AM

Forever. Twenty years.

JC

Then you’ve been in Switzerland just as long as I’ve been in the USA. Switzerland is a foreign country, it’s not Germany. So you have the view of Germany from the outside as an East German who grew up partly in the former West Germany and then saw the reunified Germany. How do you see Germany against your personal background? What does that mean to you, personally but also as an artist?

AM

I become much more German in Switzerland, because I am perceived much more as a German and treated as a German. In Bavaria, I was more of an East German.

I like this being foreign. I like it. In the beginning, it was difficult as well. Switzerland was much more encrusted then, it wasn’t very open. Zurich is not Switzerland, of course. You have to say that, too. Because of the bilateral agreements, there are many more foreigners in Zurich now. When I started studying, it wasn’t like that. Then, I found it all very difficult. But it has become very easy to live in Zurich. You can choose the people you want to see. [laughs] As a German, it’s a bit more difficult in Switzerland. For the Swiss, Germans are often too fast, too loud, too self-confident. Of course, that’s a total turn-off.

Now I can look at Germany in a completely different way. I also feel very connected. I realize how deeply it is embedded. I don’t know whether that is being German, but I know how much of a connection I have to the country of origin. It’s actually much more the East than Bavaria. Bavaria also influenced me, but not as deeply.

I notice it very strongly when it comes to language. German language in general, words that trigger me, that somehow are quite old and make something vibrate and sound in-between. Language delimits, but it also opens up a world. It influences perception. It is very powerful and it can be a tool. But it can also be deficient, have many gaps, and not describe things.

I think the German language is an absolutely beautiful language, even if it is a harsh, harsh language. But I feel at home in it. When I make work, I always try to describe or explore this gap that you can also find in language. To show or try to tell things that can’t necessarily be told with language either: Gaps, vibrations, things that can happen where spaces open up that cannot or cannot yet be described. In that sense, the German language has something to do with my work.