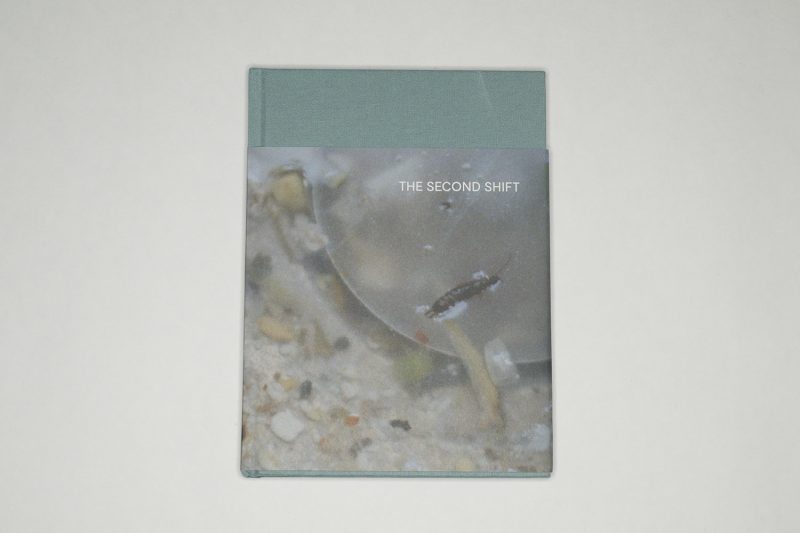

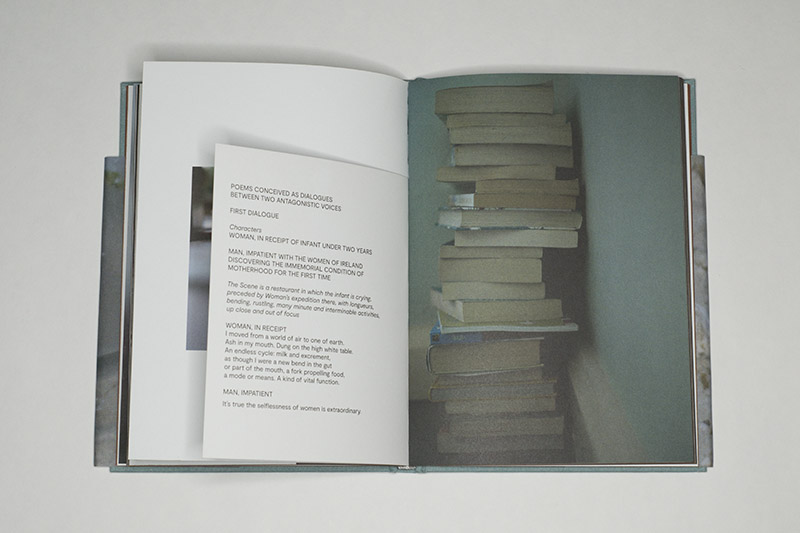

This article is the first in a new series entitled “In Hindsight”. In a nutshell, I am going to be discussing photobooks. But unlike in the case of the photobook reviews I will here focus on older books. There really is nothing wrong with the reviews, but I frankly have grown a little bit tired of only discussing/reviewing new books. With many books, their true value and merit reveal themselves only with time; and a lot of books that should get some attention (or that maybe should get re-evaluated) simply don’t (or never have), given the flood of new books and circumstances that in retrospect might not even be that clear.

The idea here is not to create some sort of Parr-Badger effect, where a bunch of old books are being turned into collectors items. However, if I manage to lift a book from an obscurity that I feel is completely undeserved then I am not going to be too worried about it (and I will have to live with its possible Parr-Badger effect).

Lastly, I am planning to add some new features (types of articles) to this site (or revive older ones). I also just started a Mailing List, hoping that with time, it will allow me to ditch social-media use completely. You can sign up here, where you can also see some already existing material (which includes my motivation for doing so).

It’s a Mailing List, not a Newsletter (there will hardly be any news). And while the site I’m using allows me to evaluate statistics, I am not going to do that. In other words, I’m not going to look at who clicked on what or how many people read this or that… I find that a bit creepy. If you have any comments or recommendations or requests for the Mailing List, feel free to each out via email!

My basic expectation is that when I look at a book that is 20 years old I will see its age. I will see that its sensibility is one that has become a bit dated, whether as a whole or in part. My expectation might simply be based on having experienced this process many times in my lifetime. Most jarring examples are probably provided by re-encountering something that I appreciated quite a bit when I was younger, or something that I simply didn’t notice all that much in the past but that now strikes me as dated.

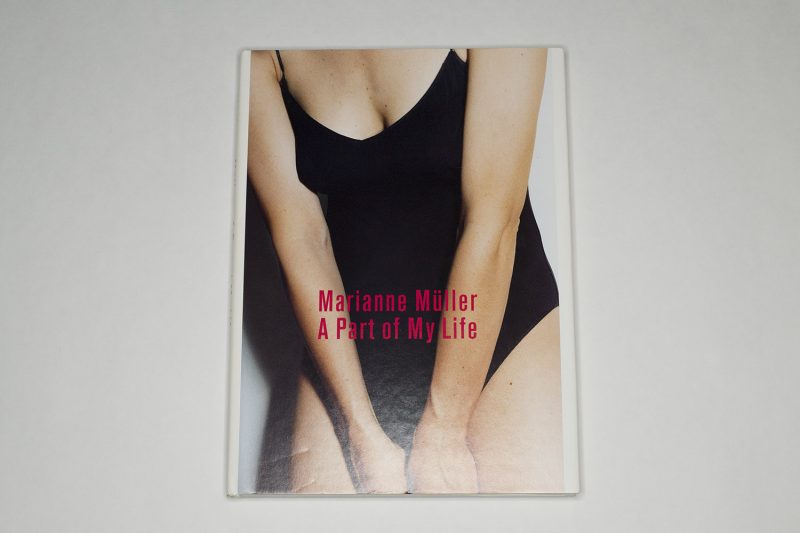

Much to my surprise, when I first received Marianne Müller‘s A Part of My Life in the mail, some time in late summer 2019, the book looked as if it had been published that year — and not in 1998. To begin with, despite its very low price ($4.77 on US Amazon), the book arrived in pristine condition in its original shrink wrapping. Really the only thing that would betray its original publication date was the treatment of the typography. But the photographs themselves appeared to have been taken for the moment we are now experiencing (or, possibly, re-experiencing — it would take an art historian specializing in feminist art to dive more deeply into this).

I had discovered the book in Walter Keller — Beruf: Verleger (reviewed here). Leafing through the pages of spreads of book published by Keller’s Scalo publishing house, there were four pictures from the book that made me look into their origin. I quickly found that the book could be had for less than $5 easily, so I ordered a copy, not really knowing what to expect. But I didn’t order the book based on its price — something about those four pictures intrigued me.

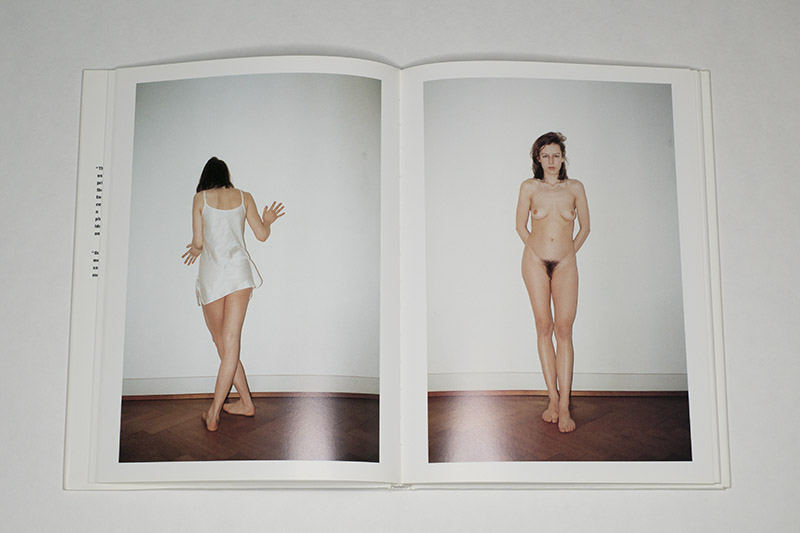

The bulk of the book consists of self portraits, in which the artist scrutinized her own body. There are a number of photographic approaches (and cameras), ranging from pictures made at arm’s length to pictures taken with a tripod, some in black and white, but most in colour.

I’m obviously looking at the book against the background of the selfie craze (which, for the record, unlike many of my colleagues I have absolutely no problem with), so there is a sense of familiarity for me in these photographs. Still, the book is radiant with a sense of exuberant self discovery that I can’t easily recall seeing elsewhere.

Having seen Talia Chetrit’s work a little earlier, there also was that reference; but while I appreciate some of that artist’s photographs quite a bit, in the end I’m left feeling that what I am made to look at is a cerebral exercise first and an artistic project second (for me, quite a bit of contemporary photography falls into this category).

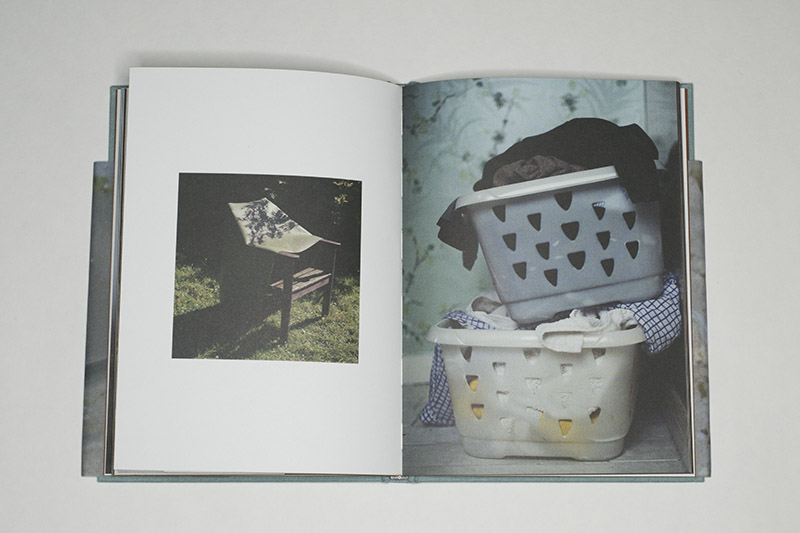

Müller’s photographs, in contrast, never made me feel that way. Another major difference is provided by the fact that the Swiss photographer weaves in what you could call still lifes. There is, for example, a photograph of a maroon dress on a hanger — turn the page and you see the same dress on the artist’s body. Now, this description might hint at this sequencing being cerebral or, even worse, didactic, but in the book it’s neither. It works.

And then there are what we could call the travel photographs, which appear to have been taking with any one of those 35mm film cameras that would produce a time stamp in the frame — a device that at the time was very popular (this is the only aspect that betrays the book’s time of origin, even though it is not as intrusive as one might imagine). These pictures arrive out of the blue, and much like everything else in the book, they blend in seamlessly. I found myself surprised by how well this works as well.

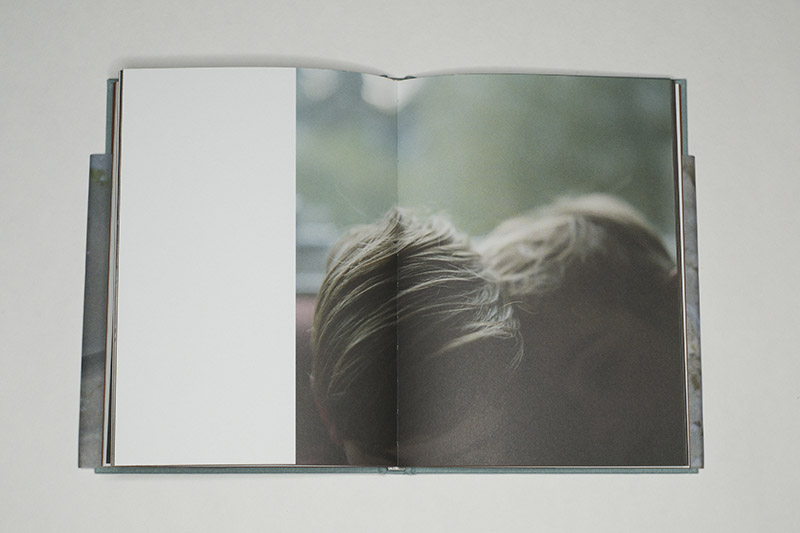

There also is the presence of another person, a man, who remains faceless. There are bits and pieces of his body — a hairy leg here, part of his torso there. The book culminates in a section that is openly sexual in a way that all the others are not. A close-quarter examination of the artist’s body leads up to a spread in which they’re seen fucking.

I’m finding myself at a loss how to properly attach words to what’s on view. They make love, but what they do is more carnal than that. (English is my second language, and I’ve always found that phrase clunky.) They fuck, but there is the harshness implied by that word’s rough consonants, clustered around the short vowel, that somehow seems too harsh, too carnal. In the book, the act’s very harshness, the it being animalistic, does not deny the sheer pleasure and delight and shared agency — and it is exactly this aspect that had me startled.

I can think of an endless number of books, where a male photographer photographs his consort, his — ugh! — muse (oh, how I hate that word!), while being engaged in sex, and almost inevitably, the submission is all-encompassing. The woman submits herself to these acts, being a passive receptacle of male dominance and power (think Araki, think d’Agata, … — it’s so infuriating to witness how many examples there are and how celebrated these brutal photo machos still are).

To see a female artist produce a book that not only openly asserts her own agency, an agency denied to the macho’s “muses”, but that also embraces all that is pleasurable between two equal partners — that shows that another world is indeed possible, a world that even 20 years after the book was first published still only exists at the margins or in very narrow circles of photoland.

A recent survey book of photobooks by female photographers is entitled How We See. I’ve always thought that that’s such an apt title. It’s particularly apt to describe A Part of My Life as well: this is how a young woman sees her body, her life; this is how this seeing has translated into photographs — in John Berger’s phrase a way of seeing; and not it’s up to us to engage with it.

Ironically, large parts of the book will never be seen online since the photographs run counter those Puritan “community guidelines” established and maintained by American social-media companies. Those guidelines censor female bodies much more than male ones, and they largely cement a patriarchal, male-gaze centered engagement with the world — where scantily clad so-called influencers are fine, but other women celebrating their bodies and sexuality are not. So if you’re interested in the work, buy the book.

A Part of My Life; photographs by Marianne Müller; 127 pages; Scalo; 1998