I remember asking Rob Hornstra what he was going to photograph next, given the Sochi Project had ended, and he and his writing partner Arnold van Bruggen had been barred from entering Russia. Rob told me he was working on something about his neighbour, a man next door. Somehow, I was very surprised. But I realized quickly that my being surprised was based on my own assumptions, on who I thought Rob was as a photographer, or maybe on how I thought he would be working.

After all, if you travel all the way to the Caucasus to attempt to untangle the cultural and societal conditions what you’ll end up doing if you want to do it well is to look deeply into the lives of the people living there, to try to infer the larger situation from the many stories you’ll be encountering. At least that’s what made the Sochi Project so successful for me. Rob and Arnold could have adopted the infamous helicopter approach, where you go to a place for a week (at best), take the set of pictures that your audience expects to see, and leave it at that (an approach still widely used in photojournalistic circles). But they didn’t. Instead, they decided to invest time, to look into people’s lives as deeply as they could. And that’s what Rob did with the man next door, which is now available as the eponymous book.

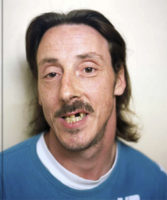

In today’s parlance, Kid, the man next door, was a troubled character (for reasons of privacy, his last name is withheld throughout the book). Rob would hear him argue loudly with his wife, before she left, taking their son with her. Kid, writes Rob, “really liked to help me, for example by keeping an eye on things when I was working abroad.” In return, “I often lent him my phone when he ran out of credit and helped him with his mail because he had difficulty reading.” Kid’s life progressively took a turn for the worse, and at age 42, his body was found floating in a canal.

Through a string of reports produced by Dutch authorities, Man Next Door chronicles Kid’s increasing struggles, a seemingly endless string of events that on their own would have been petty affairs, whether it’s public intoxication or noise complaints. But as becomes clear, the overall effect is cumulative. Rob’s own photographs accompany these reports. But they tell a somewhat different story. Kid’s increasing problems leave their traces in his physique. But given how comfortable he is in the photographer’s presence, as a viewer you start feeling for this man. The book makes use of some archival (family) pictures, and there is a variety of photographs describing the apartment or the pet snake (including its feeding).

The portraits really carry the book. It’s not that they tell a different story. But they manage to pierce the armour that we all have surrounded ourselves with when confronted with those in need. Whatever you might want to say about Kid, he was a man in need, and when society was unable to provide for those needs, there was not going to be a happy ending. Seen that way, Man Next Door amplifies the humanism that underlies all of Rob’s work, a humanism a bit masked by the style of photography and the intensely smart storytelling, with its many different devices.

It’s really simple: if you want to make people care about who or what is being depicted in your picture, you first have to care yourself. Rob cared very deeply for Kid.

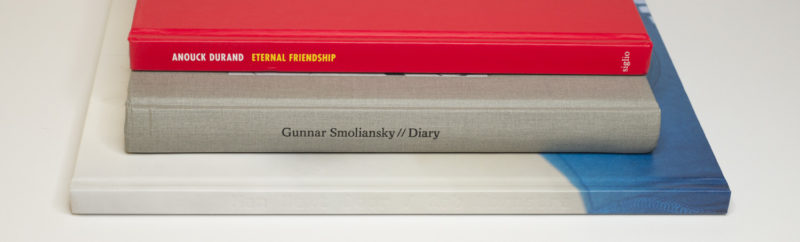

Man Next Door; photographs by Rob Hornstra; 96 pages; self-published; 2017

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6

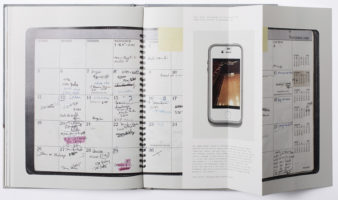

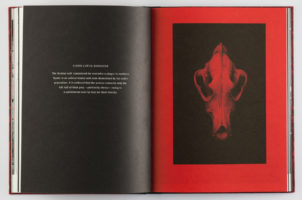

Growing up, I would see photographs and text combined in photonovels quite a bit. There’s something corny and amazing about them. Maybe it’s that background that has me enjoy Anouck Durand’s Eternal Friendship so much. Durand combined a vast set and variety of archival imagery to tell the story of Albanian photographers visiting communist China to learn how to print colour photographs. The narrative device used is the first-person account: we are made to read the (imagined) words of one of the photographers, following him along, being made to share his anguish concerning the many complex problems created when two weird and brutal communist regimes interacted.

Given the source material, there was the immense risk of the result being too cute or cool. As I noted before on this site, archival materials are tricky for that reason: they’re often visually very stimulating, especially when as a viewer you have no access to symbols that point at something altogether frightening. Their patina can mask what’s underneath. With her narration, Durand deftly avoids that pitfall. As much as I enjoy seeing the materials, there always is that intensely oppressive effect that has me realize that those depicted had to live their lives in a constant state of sheer terror, with minor missteps possibly resulting in major repercussions. It’s a world we now cannot imagine any longer, even though autocrats across the world are trying their hardest to bring it back.

In a sense, the format used for Eternal Friendship is so specialized and the craft itself is so well done that I can’t easily see too many other books being made this way. Maybe that’s a good thing. I’d hate for the photonovel to become a trend now. In light of my thoughts about photographs and text, the book lays down a very clear marker for how pictures can be combined with text to great effect. Even if they don’t want to replicate the way narrative is built here, photographers for sure might want to take note of this book

Eternal Friendship; archival photographs compiled and narrated by Anouck Durand; 100 pages; Siglio; 2017

(not rated)

Even though I have been following the world of photography for a while now, there still are new discoveries. Inevitably, many of those discoveries are young artists. But occasionally, someone will pop up on my radar who has been making photographs for a while, leaving me to wonder why or how I had not been aware of her or him. In part, this might be a consequence of my usual modes of engagement with the medium, much of it in the digital sphere. Someone who has been photographing for 30 or 40 years is unlikely to be found on Instagram, say.

But the photobook provides a welcome corrective. Thankfully, there are enough publishers who will produce a book around the kind of work that either gets lost in all the digital noise or that isn’t even included in said noise in the first place. As far as I can tell, that’s the case for Swedish photographer Gunnar Smoliansky. Gerry Johansson sent me Diary in the mail, noting that he (Johansson) had now become a publisher of other people’s work. Holding the book I thought I was able to see appeal of Smoliansky’s work for Johansson. But of course, it isn’t quite that simple.

There is a shared sensibility between these two photographers. Both photograph in b/w, using the square format. Smoliansky will often also focus his attention on visually organizing the square in what on a superficial level one might consider a formal exercise. But he will not stop there. Looking through the book, whenever I thought I had got what he was after there was a surprise that would jolt me. There are a fair amount of essentially street photographs in the book, mixed with other slightly idiosyncratic observations. In addition, if I didn’t know any better I would have guessed the pictures had been taken in Eastern Europe, with a sense of slightly resigned dread going through the work.

Diary was produced with source material photographed from the 1960s all the way into the 1990s. You might imagine this would be apparent when you look through the book, but it isn’t. In part, this might be the editors’ making. But as an editor, there is only so much you can do with what you’re given. In other words, it’s Smoliansky’s world that we are being exposed to here: a photographer going about his business doggedly over decades, producing photographs that now get to hopefully find a larger audience.

Diary; photographs by Gunnar Smoliansky; 204 pages; Johansson & Jansson; 2017

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 3.0 – Overall 3.4