There are so many photobooks still waiting to get reviewed here that I am literally surrounded by piles of them. Until the end of the year, I will attempt to reduce their heights as much as I can. There will be, however, no “best of” list from me at the end of the year. I think this whole list business at the end of the year is completely out of control, and I don’t think it does photobooks any good to spend four or five weeks out of 52 obsessing over which book got on which list. In much the same fashion, there are now way too many awards with shortlists (that usually aren’t so short) attached. I spend a lot of time looking at photobooks. But if even I can’t keep up, I don’t even want to imagine what it looks like to the casual viewer.

But how, you might wonder, might we find a good photobook to buy when there are so many? OK, sure, it’s nice to buy a book because any of the usual suspects (incl. me) suggests so. But that’s a very passive way of approaching a problem, at the core of which should lie art and, by extension, enjoyment, a lifting of the spirit. As much as I get the idea of following someone’s advice, the true enjoyment is to be had in the discovery. So if you’re unsure which book to buy, take a little risk — get something not because it has been vetted by the aforementioned usual suspects, but because it intrigues you.

Along these lines of thinking, these reviews here (or in the full archive) are not intended to establish a fixed hierarchy, a canon of sorts. Instead, I see them as starting points of a discussion, as the impetus for every person’s engagement with a book, at the end of which there might be full agreement or disagreement with what I write. As much as I still enjoy the usefulness of my rating system (it helps me focus), what really gets me is when people only talk about books based on what rating it got. The ratings only cover a part of what’s important about a book, and often enough the ratings are also at odds with the actual review. Having said all that…

If I had not finished writing my own textbook about photobooks, I would have certainly included Peter Dekens‘ (un)expected as a prime example to study. When making a photobook, the task at hand is to give a body of work the appropriate form in such a way that the resulting object supports and enhances what needs to be conveyed in the best possible way, without drawing attention to itself. This simple description of the process is fraught with difficulties, some of them inherent to photography (editing and sequencing), some of them coming with a territory where a lot of artists have only a partial understanding of the role of, let’s say, design (I’m being a bit generous with my wording here). Consequently, most photobooks fall short of what they could have been, because they’re badly edited and/or sequenced, or they’re boring or too flashy, or whatever else.

They key to any photobook is that while the underlying idea of how to make it is what I wrote above, that process will have to be approached on the body of work’s terms: what does this body of work need, for the resulting object to convey exactly what’s going on? As I noted already, (un)expected does this perfectly. Given the work itself, which centers on the frequency of suicides in a small area in Belgium, I don’t see anything that could have been improved in this book.

The approach itself is simple, and simple solutions are the ones that tend to win out in good photobooks in nine cases out of ten. There are two subgroups of images, the first one black and white photographs of the kinds of somewhat anonymous urban buildings commonly encountered in this part of the world. People are absent, and in many of the houses, their shutters are drawn down, hinting strongly at a sense of isolation. The second group of photographs features colour images, and they are a lot more diverse in what they depict, ranging from portraits to landscapes to still lifes, even to images of documents. In the book, the b/w photographs form the shell of the book (much like the houses do). The colour photographs are interspersed in sections in between, using a slightly reduced paper size.

As a book, it’s really just one signature. But the way the folios are stacked creates very distinct parts, in which each colour section introduces someone who has lost a loved one who committed suicide. In these colour sections, text is used to tell that survivor’s story — there really is only so much you can show in pictures, after all. So it’s really a documentary photography project that uses the form of the book to convey and amplify its message. It is precisely the way the colour and b/w sections alternate that helps drive the intensity of the survivors’ stories. It is as if as a viewer one went from one house to the next, to encounter these people and to have them tell you their stories. The addition of the photographer’s own story only adds in intensity (his mother committed suicide).

Photographers tend to get very hung up on ideas of storytelling. If we were to dissect (un)expected we would find it connect the individual survivors’ stories not just through their connecting thread. Through its physical form — production and design, the book manages to involve the viewer in ways that a more traditional documentary photobook probably would not have been able to achieve.

(un)expected; photographs and text by Peter Dekens; 144 pages; The Eriskay Connection; 2016

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 4.0, Production 3.5 – Overall 3.8

Photobooks really are like dogs. All dogs have a lot in common, but it’s sometimes hard to believe that when you see two very different breeds of dogs next to each other. Just like (un)expected is a very good photobook, so is Curran Hatleberg‘s Lost Coast, albeit for mostly very different reasons. It looks differently, it feels differently, you’ll engage with it differently, and it even smells differently. This is all too obvious to point out you might think, but it still is a point worthwhile making: there simply isn’t that one type of photobook. What we sum up under the term “photobooks” is as varied a collection of different types as the animals we call “dogs.”

Maybe the most obvious difference between these two books is the general way their stories are being told. As I already noted, in the world of photography you run into the strangest ideas concerning storytelling, starting maybe with the idea that photographs are very bad devices for storytelling. This is very obviously not true at all, as should be very clear from all those photobooks that tell their stories in a convincing manner.

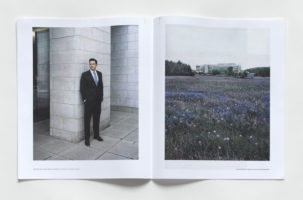

Dekens’ (un)expected tells its very specific, yet ultimately amorphous story (suicide in a small region in Belgium) through a collection of very specific stories (individuals who lost a loved one). Lost Coast, in contrast, cannot be described this clearly. Instead, it follows in the well-established tradition of books where a sequence of carefully edited pictures add ups to a lot more than, well, an album does. With a few exceptions, each spread presents a single photograph on the right page, offering no text, not even page numbers.

As is probably obvious, such an approach to photobook making can only succeed if the pictures in question can carry the burden that is being placed on them. As anyone familiar with this photographer’s work is well aware of, they can. But given that I engaged in this cross-comparison of two very different books, one approach to book making is not better than the other — at least not for me. I’m perfectly happy to live in a world where I can have both (in fact, there are a bunch more). If every book were made along either one of these two lines, I’d be bored out of my mind. Consequently, I’m happy having different books where photographs play different roles, with different weights. Lost Coast had me dive into its pictures a lot more — this is both a necessity, not just for me, but for any viewer: you only have the pictures, so you need to explore them carefully.

But it’s also a reward, given that Hatleberg is one of the very best American photographers right now. In many of these pictures you can see echoes of those that came before him. But unlike the imitators who successfully take an earlier artist’s mode of work, to continue it without much (if any) variation, this particular photographer appears to be synthesizing what came before him into something else, along the way redeeming some of the ideas that went into the staged-narrative dead end (remember how hot that was before the New Formalists finally put us all to sleep?).

Lost Coast‘s view of the country is bleak. Ostensibly only focusing on a specific region, much like in Gregory Halpern‘s ZZYZX there is a lot more resigned existence than anything else. In part, that is the American tradition in the photobook: books about America tend not to be cheerful. Where they’re not outright bitter or cynical, they’re resigned and filled with sadness. This ought to tell us something. There are lessons here. Maybe these lessons will be learned before the next election.

Lost Coast; photographs by Curran Hatleberg; 100 pages; TBW Books; 2016

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.5, Production 3.5 – Overall 3.9

Barbara Probst is one of those singular photographers who single-handedly pushed the boundaries of photography in a very specific direction, forging ahead on her own. Seeing her work online or in a book almost makes no sense, because it is in the installations of her multi-panel pieces that a large part of their power is revealed. A piece might consist of two, three, or many more photographs, each of them showing an aspect of the very same moment, employing a variety of different vantage points (at times, colour and b/w images might be mixed).

As photography centered on the very nature of the medium, maybe the only other comparison that comes to my mind are some of Paul Graham‘s most recent bodies of work, such as A Shimmer of Possibility or The Present. Where Graham dove into the dimension of time and less so on vantage point, Probst has been drilling deep into the latter’s bedrock, creating ever more complex and dizzying pieces. Curiously enough, for me, it’s Probst’s pieces that ultimately feel more convincing and thrilling, even though in terms of how cerebral they are they outgun Graham’s by a lot. Probst’s sense of discovery somehow feels a lot less forced than Graham’s.

Probst’s latest work might be the one most suitable for the format book. Published as 12 Moments, these twelve pieces attempt to distill the overarching ideas of the past decade’s work into two separate photographs. Unlike previous two-image pieces, which tended to involve minute shifts, resulting in very small differences, these newer attempts are a lot more daring. There inevitably is that moment of recognition, when the viewer is able to connect the pictures.

But this moment of recognition arrives at different moments in these pieces, making some more successful than others. Ultimately, all of Probst’s pieces rely on an astonishing degree of visual cleverness. Where they succeed, as they often do, is when they manage to move beyond being merely clever, where, in other words, that viewer’s moment of recognition is dwarfed by the unbroken power of visual delight.

12 Moments; photographs by Barbara Probst; essay by Robert Hobbs; 68 pages; Hartmann Projects; 2016

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 3.7